This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Heather Exner-Pirot and Evan T. Bloom, November 10, 2022

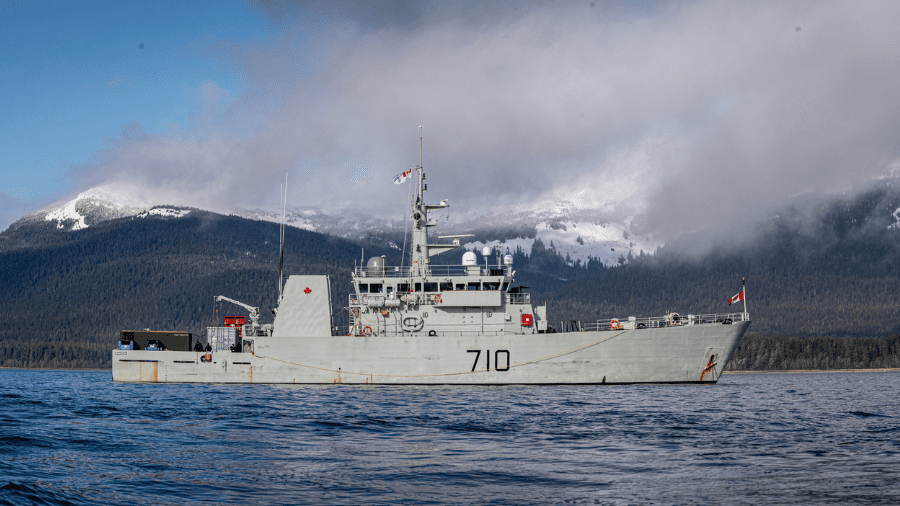

The Arctic Council — the main diplomatic forum of the eight Arctic states — has long been described as an exceptional space for co-operation with Russia, kept insulated from East-West rivalries. But the war in Ukraine has posed an unprecedented challenge. Russia’s illegal invasion means it can’t be business as usual. Arctic relations are in turmoil, with implications for Canada’s approach to regional co-operation and its relationship with Russia.

A week after Russia’s invasion, the other seven Arctic Council states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the U.S.), announced a “pause” in its work. In June they determined that only projects without Russian participation could proceed.

Despite this enormous rift, the West still shares interests with Russia in the Arctic — addressing climate change, protecting the environment and advancing sustainable development for the peoples of the Arctic. Russia has half the land mass, two-thirds of the people and three-quarters of the GDP in the region. There can be no meaningful progress on core pan-Arctic issues if Russia is not engaged.

That leaves the Arctic Council in a quandary. Other forums exist to address Arctic issues: the International Maritime Organization, various multilateral fisheries arrangements, and numerous climate and environmental agreements, for example. But the Arctic Council, uniquely, includes formal Indigenous representation through six organizations representing the Inuit, Sami, Aleut, Gwich’in, Athabascan and Russian Indigenous peoples. There is valid concern that simply hiving off Arctic issues to other international bodies will diminish the influence of Indigenous peoples in matters affecting them first and foremost.

The organization has been effective for shaping Arctic policy and values, and there is no desire to abandon it. Indeed, the seeds planted by Canada when it first proposed the creation of the Arctic Council over 25 years ago have given rise to an organization that has accomplished much and would not easily be replaced. The Norwegians, who are supposed to take over chairmanship of the Arctic Council from Russia in May 2023, have made it clear that they intend to move forward.

If it seems certain that the Arctic Council’s work will continue in some manner, what are the options available for addressing Russia’s participation?

The other seven Arctic states are committed to a rules-based international order. As such they must consider the rules that govern the Arctic Council, which affirm that Russia is a member, and that decisions are to be made by consensus.

And so the first option on the table is to continue the Arctic Council as it has been, and ask Russia to agree, openly or tacitly, not to participate. This strategy leaves the door open for a resumption of Arctic Council activities if or when the situation with Russia normalizes. Depending on your position, this is either an elegant solution or a naïve stopgap. And it carries the obvious risk of relying on Russia to voluntarily stay away.

The second option is to continue the Arctic Council without Russian concurrence: maintain its working groups, secretariat, and rules of procedure but evolve to a membership of just seven. This option would assume that no normalization with Russia can take place in the next five or more years, and rather than depend on a gentlemen’s agreement to keep Russia from attending meetings, just make a clean break. This path, in effect kicking the Russians out while they still chair the council, bears the risk of Russia concluding it can never rejoin the organization.

The third option is to take the opportunity to create something new; to grieve the end of the Arctic Council but then update and reform its structure so it can provide more practical leadership in a world confronting simultaneous geopolitical, resource and climate crises. But those same crises mean it will be hard to muster the time and energy to push a new body forward, and its effectiveness for the Arctic region as a whole would be limited without Russian participation.

Canada will need to evaluate the options carefully. Even though the next steps need to focus on whether and how Norway would take on its chairmanship in May 2023, as a consensus-based organization the decision is equally up to Canada.

The Arctic Council has been a place where optimism has been generally rewarded, and the prevailing attitude of those currently involved suggests that this attitude perseveres. But it will be a rocky road. Any plans to keep a door open to Russia ahead of the start of the Norwegian chairmanship will be closed politically if the situation in Ukraine gets any worse; and there is ample opportunity for it to get worse.

Heather Exner-Pirot is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and Visiting Scholar at the Wilson Center. Evan Bloom is a Senior Fellow at the Wilson Center and a former U.S. diplomat engaged for three decades on Arctic governance and foreign policy.