Pursuing rapid change risks disrupting established institutions and practices that conservatives are usually inclined to preserve, writes Philip Cross.

Pursuing rapid change risks disrupting established institutions and practices that conservatives are usually inclined to preserve, writes Philip Cross.

By Philip Cross, May 23, 2019

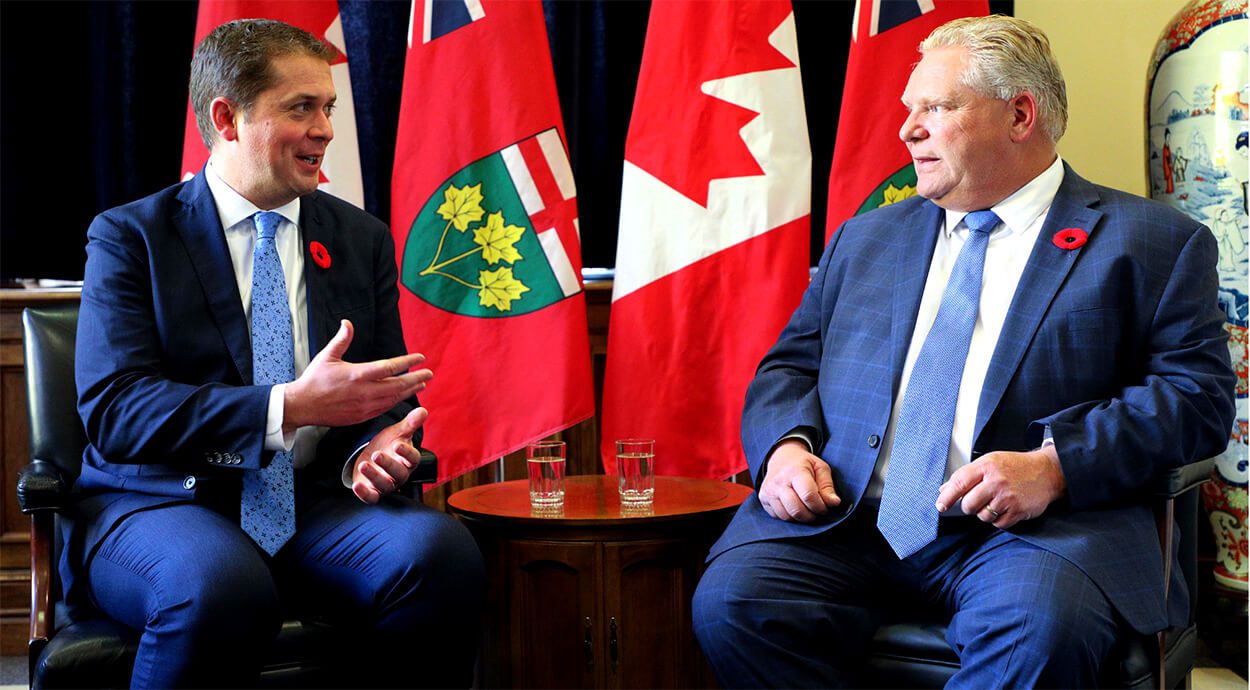

The wave of conservative provincial governments elected across Canada over the past year all face the same challenge every new government must decide: whether to implement its mandate gradually over time or all at once. The pressure on a new government to proceed rapidly always comes from their supporters, anxious for change, and the media, a legacy of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s dramatic first 100 days when he laid the foundation for the welfare state and resuscitated the banking system.

Conservative governments, however, face an added complication in choosing how fast to proceed because conservatism inherently favours gradual change. The debate between gradual change versus the “shock therapy” approach has been around for centuries. Rapid change contradicts the gradualism at the heart of mainstream conservative thought. After all, modern conservatism was born in response to the upheaval of the French Revolution, which dislodged institutions such as the church and family from their traditional moorings. David Hume warned that “Given the fallibility of human reason and the complicated, variable nature of the political world, we should be wary of grand schemes for radically restructuring society.”

Pursuing rapid change risks disrupting established institutions and practices that conservatives are usually inclined to preserve. Disruptive change succeeds only when backed by a strong social consensus such as mobilizing during war, hitting the debt wall when lenders balk at funding government debt, or adopting strict monetary control to end bouts of high inflation.

The pitfalls of shock therapy are epitomized by Russia’s attempt at a rapid transition from communism to capitalism. This failed so abysmally that Russian president Boris Yeltsin later apologized, asking the “forgiveness of those who hoped that with one push we could transition from the dark, stagnated totalitarian past into the bright, prosperous and civilized future.” Today, Russia’s economy represents more a kleptocracy than market-based capitalism.

Stephen Harper, in his recent book Right Here, Right Now, touts the virtues of the incrementalism he practiced for a decade as Canada’s prime minister. By making small but constant changes, he argues that “incrementalism proved to be the best method of evaluating the effects of policy reform and of building political support for further change.”

The new governments in Ontario, Quebec and Alberta all seem to be heeding this advice to proceed cautiously, even if critics howl about symbolic changes like Quebec’s bill on religious symbols or Ontario’s halving the number of city councillors in Toronto. Fiscally, Ontario and Quebec are only trimming the rate of increase of government spending rather than shrinking outright the size of government. While the Ford government in Ontario has made numerous small cuts to many programs, there is no fundamental change to the delivery of health and education services; not building a university that never existed is hardly on the scale of closing existing ones. In Quebec, Premier François Legault’s first budget was notable for how it maintained the growth of existing government services and resisted broad tax cuts even as its budget surplus continues to grow.

Premier Jason Kenney’s new conservative government in Alberta probably has the strongest mandate for fundamental change. Kenney’s mandate is mostly to reverse the radical changes made by Notley to taxes and environmental regulations. Rolling back taxes and regulations to the way things were four years ago is not a betrayal of conservative principles but their reaffirmation. While Alberta’s fiscal plan will not be revealed until its fall budget, appointing the eminently sensible former NDP Saskatchewan finance minister Janice MacKinnon to head its spending review suggests an incremental approach.

Some conservatives are not convinced of the wisdom of gradual change. By accepting gradualism, conservatives end up defending actions that can be fundamentally against their basic principles, such as keeping the misguided minimum wage hikes enacted in Ontario and Alberta by the previous governments. The conservative philosopher Peter Berger articulated the conundrum that “American conservatism defined itself by its opposition to New Deal liberalism. The existing social order, however, had been decisively shaped by New Deal liberalism. The American conservative opponent of liberalism found itself in the position of defending a status quo founded on the institutional and ideological products of precisely this liberalism.” Preserving the established order even if it is liberal is what provoked Friedrich Hayek to write his famous essay “Why I Am Not A Conservative,” arguing that conservatism “by its very nature cannot offer an alternative to the direction in which we are moving.”

Milton Friedman summarized how major shifts in public policy almost always occur gradually over long periods. Change starts with new intellectual ideas, usually in reaction to the failure of earlier ideas to fulfill their promises. The new intellectual tide gains popular acceptance as dissatisfaction with existing policies grows. Dissent pressures governing institutions to change policy, ultimately overwhelming the status quo. The process needs years to unfold unless spurred on by a societal or economic crisis.

Philip Cross is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.