The design of many low-income benefit programs often put low-income Canadians in the difficult dilemma of choosing between pursuing paid work and losing public benefits. That’s where the Working Income Tax Benefit comes in, write Sean Speer and Rob Gillezeau: It supplements the earnings of low-income workers, while also introducing strong incentives for them to re-enter the labour force.

The design of many low-income benefit programs often put low-income Canadians in the difficult dilemma of choosing between pursuing paid work and losing public benefits. That’s where the Working Income Tax Benefit comes in, write Sean Speer and Rob Gillezeau: It supplements the earnings of low-income workers, while also introducing strong incentives for them to re-enter the labour force.

By Sean Speer and Rob Gillezeau, Dec. 7, 2016

Conservative Party leadership candidate Michael Chong’s carbon tax proposal has generated considerable political attention. What has received less consideration is his proposal to double the Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB), one of the key tools in federal government’s antipoverty arsenal. What may surprise some observers is that there is actually a broad political consensus in favour of expanding the program.

The WITB was established by the Stephen Harper government in the 2007 budget and further enhanced in the 2009 budget to help the working poor in Canada. It is modelled on the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the United States, which was introduced under the Gerald Ford administration in 1975 and has subsequently been expanded several times, with support from both Democrats and Republicans.

The policy is attractive across party lines in the US and Canada because it transfers substantial income to the working poor, while encouraging participation in the labour force. It is, in effect, a social welfare program with a strong pro-work bias, which has produced significant results. The EITC has been described as “the single most effective antipoverty program targeted at working-age households” by the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, and it counts conservative Speaker Paul Ryan and progressive Senator Elizabeth Warren among its supporters.

How broad is the cross-party Canadian consensus on the WITB? In a 2013 report on income inequality presented by the Standing Committee on Finance, the three major parties called for a further expansion to the program. Next year marks the WITB’s 10th anniversary, and there is a growing consensus in favour of expanding the benefit to help more low-income Canadians find and maintain employment to enable them to ultimately climb the economic ladder.

We add our voices to these mounting calls. Expanding the WITB would be a positive step that Ottawa can take to deliver on its promise of “inclusive growth” and to increase social mobility in Canada.

What is the WITB and what is its purpose?

The design of many low-income benefits often puts low-income Canadians in the difficult dilemma of choosing between pursuing paid work and losing public benefits. The trade-off can be steep. The clawback when one reports income can reach as high as a dollar-for-dollar, and can strongly discourage the decision to re-enter the labour force, particularly if a worker faces substantial transportation or child care costs. A basic test for good public policy should be that government benefits are carefully designed so as to minimize disincentives to engage in paid work.

Herein lies the utility of the EITC in the United States and WITB in Canada: both are refundable tax credits that supplement the earnings of low-income workers, while also introducing strong incentives for them to re-enter the labour force.

The designs of the EITC and WITB are somewhat complex (the rate for the WITB, for instance, varies among the provinces or territories), and they differ with regards to their maximum benefits and income thresholds for singles, couples, and persons with disabilities. We will return to the problems resulting from this complexity below. But their basic objectives are the same: to help the working poor find, maintain, and expand employment and still cover their basic living costs.

Evaluation of the WITB’s effectiveness is limited for several reasons, including its short lifespan and the program’s limited size and scope. There is, however, reasonable information about its usage. Approximately 1.5 million Canadians receive the benefit, at a cost of $1.2 billion per year. Department of Finance analysis provides a useful sketch of who uses it and what it means for them and their families:

- 63 percent of recipients are unattached workers. Single parents (of which 90 percent are women) make up the second largest group, at 16 percent.

- About 42 percent of WITB recipients are under the age of 30, including a significant number of people who have recently completed post-secondary education or occupational training and are searching for full-time employment.

- 53 percent of WITB recipients earn enough employment income to have had a partial phase-out of their benefits.

- Year-over-year recipients change considerably, with roughly half of people who were WITB claimants between 2009 through 2011 no longer receiving the benefit in the subsequent years, largely because an increase in their earnings. Only 20 percent of WITB claimants received the benefit in all the years between 2009 and 2012.

These data are able to tell us who is receiving the WITB and suggest that it is fulfilling its policy goals. In particular, the benefits are largely being claimed by unattached individuals who do not benefit from Ottawa’s child-support system, and most beneficiaries see their employment income increase over time.

The empirical evidence on the EITC in the United States is much richer, for several reasons. It has been in effect for over 40 years, it has undergone repeated changes during this time, and it has been subjected to regular scrutiny. Its effect has been striking:

- One estimate is that the EITC lifted approximately 6.5 million people, including 3.3 million children, out of poverty in 2015. The number of poor children would have been over 25 percent higher without the EITC.

- The EITC is directly connected with positive employment outcomes, such as encouraging large numbers of single parents to enter the workforce, contributing to higher wage growth, and even resulting in higher social security contributions and benefits. It also drove a 4 percentage point rise in mothers’ employment.

- Studies show that young children in low-income families that receive the EITC (and/or the Children’s Tax Credit), on average, have better health outcomes and perform better in school. An additional $1,000 in EITC benefits received by families with children boosts the children’s annual income in adulthood by $883, or 3.7 percent.

- 61 percent of those who received the EITC between 1989 and 2006 did so for only a year or two at a time.

- As Austin Nicols and Jesse Rothstein conclude in a 2015 literature review of EITC’s effectiveness:

Researchers have documented beneficial effects on poverty, on consumption, on health, and on children’s academic outcomes. The magnitude of these effects is large: Millions of families are brought above the poverty line, and estimates of the effects on children indicate that this may have extremely important effects on the intergenerational transmission of poverty as well. Taking all of the evidence together, the EITC appears to benefit recipients — and especially their children — substantially.

It is not surprising therefore that the EITC has been the source of considerable bipartisan support, including recent calls for further augmentations to focus on childless workers.

How should we interpret these results in the Canadian context? With a more generous set of child benefits, the effects on children of the WITB will likely be somewhat smaller. It is less clear whether the employment impacts directly associated with the WITB will be bigger or smaller, given Canada’s relatively strong welfare programs and child support programs. These unknowns reinforce the need for explicit evaluation of the WITB’s effectiveness.

How do the EITC and WITB differ?

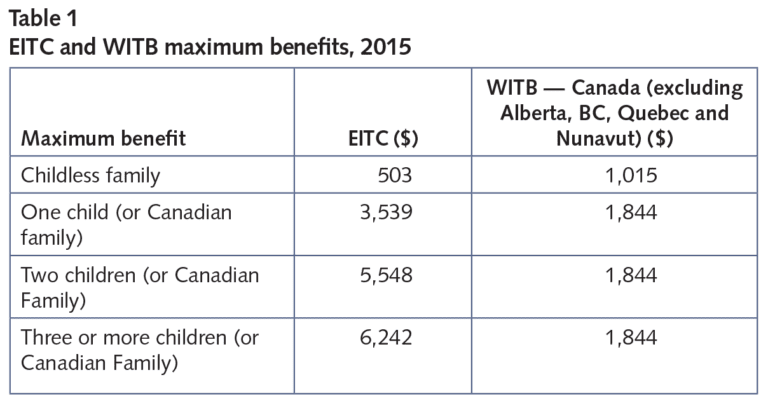

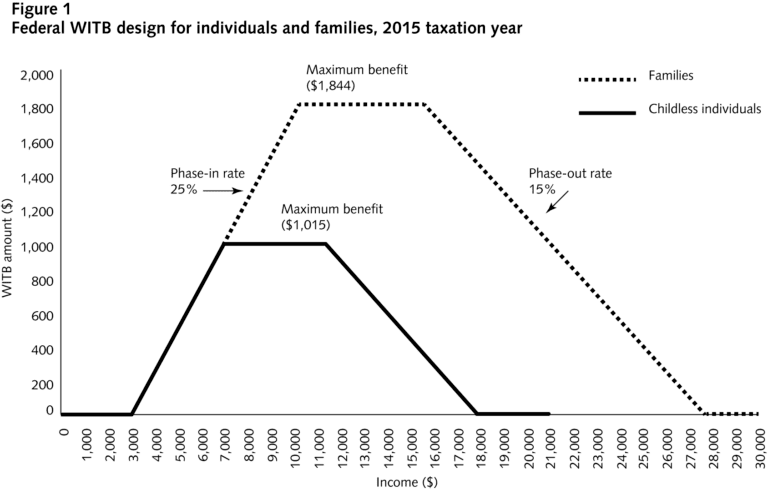

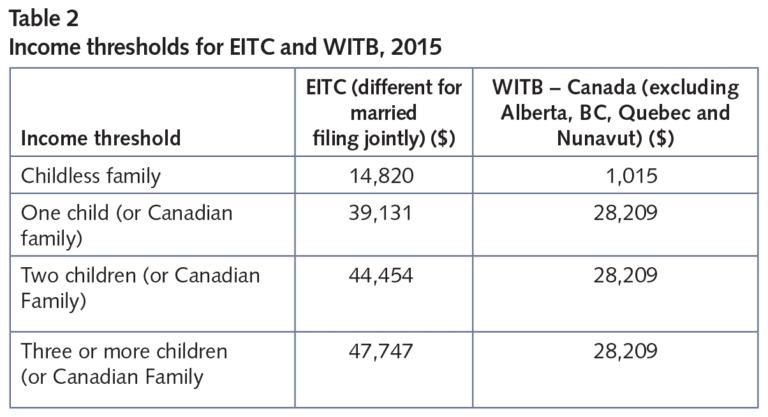

The EITC and WITB are similar conceptually, but they also share the practical feature that the maximum benefit gradually phases out based on one’s income. Yet there are also important differences between the programs. The maximum benefits and income thresholds in the EITC for (1) childless recipients, (2) families with one child, (3) families with two children, and (4) families with three or more children are different from those in the WITB. The WITB has two maximum benefits and income thresholds, one for unattached workers and one for families. The rates for workers differ among the provinces.

Figure 1 shows the WITB maximum benefit’s interaction with the income threshold and phase-out schedule for 2015. The benefit accrues at a rate of $0.25 for every $1 earned, starting at $3,000 of income until the maximum benefit is realized. The benefit then remains constant until an income threshold is reached, at which point the benefit is gradually clawed back.

Table 1 shows the different maximum benefits levels for the ETIC and WITB in 2015 (excluding those provinces and territories with separate amounts).

Table 2 shows the income thresholds (namely when the benefit fully phases out) for the EITC and WITB in 2015.

Not only is the EITC’s maximum benefit considerably more generous for those with children than that of the WITB, it also has more generous income thresholds. The upshot is, its coverage is much broader than the WITB’s. It also costs $69 billion per year (higher than the cost of the WITB, even after adjusting for population size).

There are notable differences in the two countries’ benefit schedules under these two programs: childless recipients in Canada have double the maximum benefit compared to childless American recipients, and families with children in the US have maximum benefits that are at least double the Canadian benefits. It is worth addressing the principal reasons for these differences. There are two likely reasons: (1) the low maximum benefit for childless workers in the US reflects that country’s complicated politics of welfare reform and a general American perception that childless workers should not require incentives to work (though it is notable that Paul Ryan has recently called for increasing these benefits); and (2) Canada’s system of means-tested child benefits (such as the current Canada Child Benefit or the previous Canada Child Tax Benefit) is substantial and limits the possibility of apples-to-apples comparisons between the EITC and WITB in isolation.

Why expand the WITB?

We are hardly the first to encourage the government to expand the WITB, but felt it important to add our voices to the list. Chong’s recent proposal builds on the multi-partisan support for the WITB, including the NDP’s 2015 campaign commitment to increase it by 15 percent and the government’s recent announcement of a minor increase in WITB funding of $250 million per year in response to changes to the Canada Pension Plan.

This represents a positive development in our politics. Many Canadian progressives have historically opposed income-support policies that can be characterized as incentivizing paid work. Many conservatives have for too long dismissed a federal role in anti-poverty efforts or been opposed to large cash transfers at the risk of increasing a sense of entitlement or dependence on the state. That the WITB has become a point of ideological convergence represents a positive nod in the direction of broad support for social mobility and for evidence-based policy.

The case for expanding the WITB is strong, based on the preliminary evidence from its first 10 years of existence and the considerable body of research on the EITC. But three other reasons to expand it are worth mentioning here.

The first is that the political preoccupation with the middle class has led to a perverse scenario whereby upper-middle-income earners are receiving disproportionate benefits from the federal government relative to low-income Canadians, including the recent lowering of the second-lowest tax rate from 22 percent to 20.5 percent.

It is critical that the federal tax-and-transfer system not assume a middleor upper-middle class bias such that low-income Canadians – a group that most across the academic and political spectrum agree should be the target of public support – are perversely affected. The political economy of pro-middle-class policies notwithstanding, surely we must resist a public policy outcome in which scarce public resources are shifted from low-income Canadians to middleand upper-middle-income Canadians. There ought to be a political and policy consensus that the primary goal of any social mobility agenda is to help the working poor climb the economic and social ladder, and not to disproportionately dedicate public resources (particularly deficit-financed spending) to politically relevant middle-class voters. This view should be shared by progressives who want to support marginalized groups and conservatives who want to limit the size of the social welfare state.

The second is that the recent US election shows there is a critical need for a positive policy agenda that addresses the needs of workers dislocated by automation, trade, and other factors. Canadian policy-makers must be proactive and preclude the type of economic disconnect between blue-collar workers and the political class that fuelled the recent election of Donald Trump. While the WITB is not a substitute for a broader economic package to help regions undergoing permanent, structural change, it would serve to aid struggling workers in those parts of the country and show that they have not been forgotten by the federal government.

The third is that the Trudeau government has committed to deficit spending in the name of “inclusive growth,” and the evidence suggests that incremental increases to spending on the WITB is among the most effective means of achieving Ottawa’s stated goals and priorities. Federal spending in general has increased substantially and, while some of this spending has been directed toward augmenting the Guaranteed Income Supplement and the Canada Student Grant, most of it has not been focused on the poor. High fiscal costs have been one of the primary constraints on expanding WITB in the past. But given the government’s loose fiscal policy, this constraint should no longer be an obstacle. Therefore, as Finance Minister Bill Morneau considers how to target public resources in the upcoming budget, he should consider options to substantially expand the WITB.

In any expansion of the WITB, there will be an opportunity to improve the program more broadly. We echo the recommendations from economist Kevin Milligan that the salience of the program must be increased. Increasing the richness of the benefit will help accomplish that goal, but so would shifting to a model of quarterly or even monthly payments rather than an annual refund. We also strongly recommend that the program be increased such that there is a reasonable expectation that low-income, full-time workers will qualify instead of effectively limiting it to part-time or intermittent workers This change would increase the salience of the program and also successful transitions back to full-time work. It is also worth considering options to better integrate the WITB and the Canada Child Benefit in the direction of a what would be a de facto federal guaranteed annual income, although we believe they should remain distinct programs, given their different objectives.

Expanding the WITB along the lines envisioned by Chong and others would further improve labour market incentives for low-income workers by removing the disincentives and penalties of participating in the job market. The impact could be substantial for those who are presently outside the program’s current parameters, assuming the increased resources were used to raise the maximum benefits and income thresholds. The result would be a fairer, more generous and efficient social welfare agenda. We believe that is a vision that progressives and conservatives should ultimately be able to support.

With broad-based calls to expand the program and a government elected on a promise of “inclusive growth,” it is our hope that the Trudeau government moves to substantially expand and improve this key income-support program in Budget 2017, the 10th anniversary of the WITB’s enactment.