By Adam Hummel, January 19, 2026

The arrest of Ahmed and Mostafa Eldidi in July 2024 on terrorism charges exposed what many security experts and immigration law practitioners have long suspected: Canada’s immigration vetting system is broken. The duo, planning an ISIS-inspired attack in Toronto, slipped through a screening process that’s supposed to involve four federal agencies working in concert. Instead, critical information fell through the cracks. Ahmed Eldidi received Canadian citizenship in May 2024 – just two months before his arrest – despite appearing in an ISIS video years earlier.

The problem is straightforward: too many agencies, too little coordination, and no single point of accountability. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) conducts initial assessments. The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) provides security screening recommendations. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) handles intelligence analysis. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) manages biometrics. Each maintains separate databases, uses different risk indicators, and operates on distinct timelines. When everyone is responsible, no one is accountable. The solution is equally clear: consolidate the process under unified leadership with integrated systems.

This isn’t about closing borders or abandoning Canada’s humanitarian commitments – it’s about fixing a bureaucratic structure that hasn’t kept pace with modern problems. A fragmented multi-agency model designed for a different era now buckles under increased applications, emerging security challenges, and information silos that allow dangerous individuals to slip through undetected.

The Mess: Four Agencies, No Clarity

Canada’s immigration security screening operates as a “trilateral program” involving IRCC, the CBSA, and CSIS. The RCMP are also engaged. In theory, this multi-layered approach provides thorough vetting. In practice, it creates confusion about who’s responsible when things go wrong.

Here’s how it’s supposed to work according to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and official directives: IRCC conducts initial assessments against departmental databases and risk indicators. Notably, and problematically, initial IRCC assessments are often based solely on wholly unreliable police background checks from abroad provided to IRCC by the applicants themselves. When concerns arise, applications get referred to CBSA’s National Security Screening Division and CSIS for comprehensive screening through an eight-step process. CBSA reviews internal intelligence databases, conducts in-depth open-source checks including media and social media, and consults classified intelligence databases. CSIS, operating in parallel, conducts open-source reviews, consults foreign intelligence partners, and may conduct security interviews. Both agencies must establish “reasonable grounds to believe” an applicant is inadmissible under sections 34 (security threats including terrorism, espionage, subversion), 35 (human rights violations, war crimes, genocide), or 37 (organized criminality) of IRPA. This is a specific legal standard requiring information that is “specific, credible and from a reliable source.” The RCMP handles biometric checks against criminal records. CBSA then consolidates findings and provides a recommendation to IRCC, which makes the final admissibility decision. This entire process is supposed to happen before admission to Canada.

The problem? Each agency maintains separate databases, uses different risk indicators, and operates on distinct timelines. When a border official testified to Parliament that they were unaware of the ISIS video allegedly showing Ahmed Eldidi, it highlighted a fundamental coordination failure. No single entity had comprehensive visibility across the entire vetting chain.

The Strain of Numbers

The scale is unprecedented. CBSA’s security screening backlog peaked at over 30,000 cases in 2018. Though reduced by 70 per cent by 2020, processing times regularly miss service standards. In 2024, visa refusal rates surged to 50 per cent for temporary residents – up from 35 per cent in 2023 – as officers struggled with inconsistent guidance and expectations.

But the volume problem masks a more fundamental procedural failure: the timing of comprehensive screening versus when applicants actually arrive. The law says screening should happen before admission. What actually happens: applicants often arrive in Canada – or remain here as refugee claimants – while waiting for CBSA or CSIS to complete their reviews.

In 2024, CSIS alone received over 538,000 screening requests from immigration and border officials. Years ago, a year-long CSIS check meant in-depth inquiries. Today, with over half-a-million requests annually, it means running names through databases while managers pressure analysts to clear backlogs. Thoroughness gets sacrificed for expediency.

The Eldidi case illustrates this breakdown: Ahmed Eldidi was granted citizenship in May 2024, with CSIS reportedly becoming aware of potential threats only in June – after the decision to grant him citizenship. The trilateral review process that IRCC initiated with CBSA and CSIS in Fall 2024 acknowledged “process gaps” without specifying whether these gaps mean incomplete screening, untimely screening, or failure to share critical findings before decisions are finalized. Further probing of decision-makers and legislators is critical on this point.

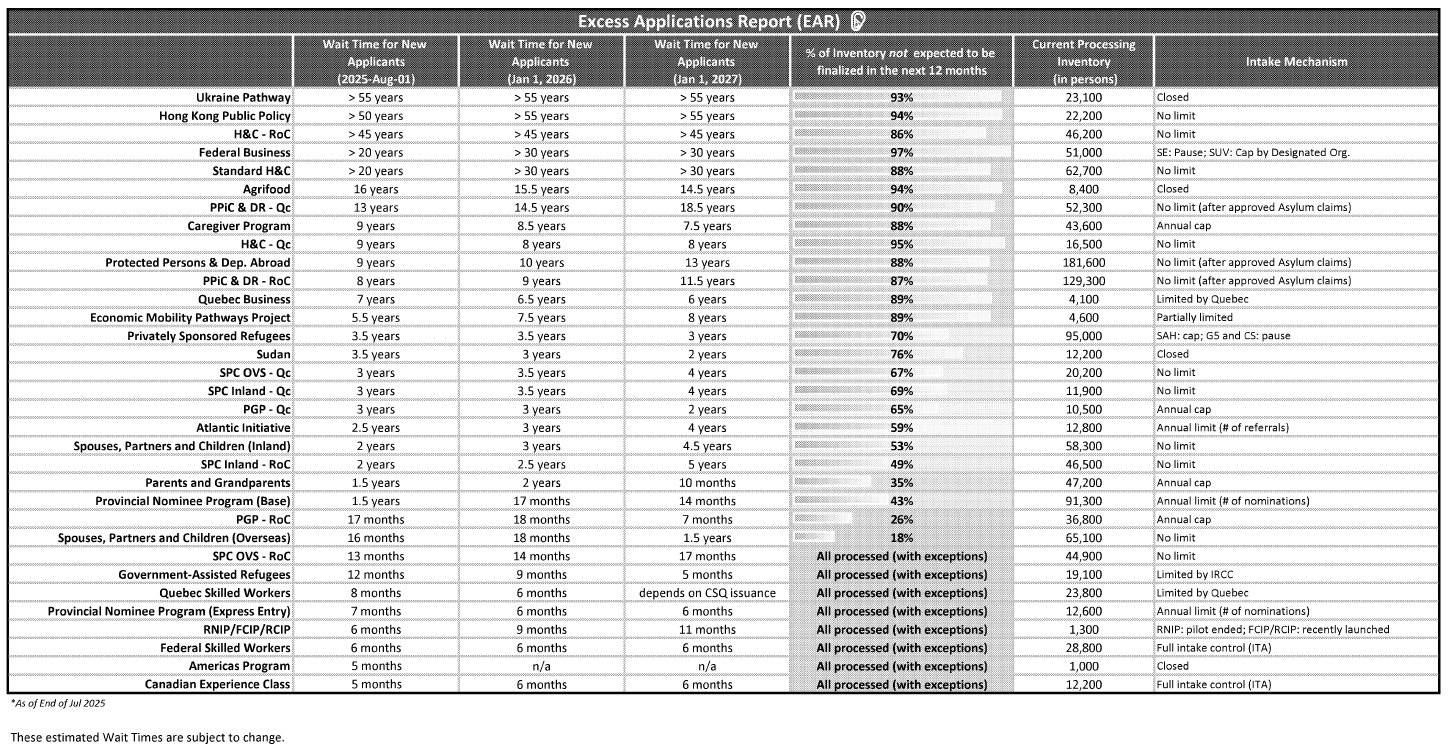

To illustrate the impact, consider these recent figures derived from an IRCC Excess Applications Report showing wait times:

By July 2025, wait times exceeded 50 years for certain pathways, including the Hong Kong Public Policy pathway, and the Ukraine Pathway. Even common streams face delays: over nine years for protected persons abroad, and over 20 years for humanitarian and compassionate applications for permanent residency. These numbers paint a picture of an unprecedented systemic strain, ripe for both abuse and error.

It raises vital questions. During these multi-year waits, are applicants living in Canada pending final security clearances? Is screening happening before they arrive, or years afterward? The law is vague on enforcement timelines, and the agencies aren’t transparent about when each conducts its review. This opacity creates a system where people may be admitted provisionally, with thorough vetting occurring – if it occurs at all – only after they’re already established in Canada. That’s not a security screening system. That’s security theatre.

What Allied Countries Do Differently

Canada isn’t alone in facing immigration security challenges, but our allies have adopted more streamlined approaches. Australia consolidated border and immigration functions under the Australian Border Force in 2015, creating clear accountability and unified command with advanced biometrics and automated risk assessment.

The United States, through Customs and Border Protection (USCBP), maintains a more enforcement-focused model with significantly larger resources. The UK recently restructured its immigration system with the Migration Advisory Committee playing a central role in evidence-based policy, ensuring screening aligns with identified threats.

Canada’s unique challenge is balancing these security imperatives with our national interests, treaty obligations, legislative intent, humanitarian commitments, and the massive recent surge in immigration. But having multiple agencies with overlapping mandates doesn’t make us safer – it creates gaps. Canada participates in the Migration Five partnership (with Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and US) for biometric sharing, but coordination remains fragmented across separate domestic databases.

The Path Forward: Four Potential Reforms

Reform 1: An Immigration Security Coordination Centre

Rather than replacing existing agencies, Canada needs a centralized coordination mechanism. An Immigration Security Coordination Centre (ISCC) could:

- Maintain a unified database accessible by all screening partners in real-time, cross-referencing foreign and domestic intelligence (and the spelling of foreign names).

- Establish standardized risk indicators across agencies.

- Provide single-point accountability for screening outcomes.

- Coordinate intelligence sharing with Migration Five partners.

- Track applications through the entire vetting lifecycle.

This is not about creating another layer of bureaucracy. It is about speed, clarity, and accountability. When CSIS discovers concerning information, CBSA and IRCC would immediately access it, and vice versa. The current system’s reliance on manual referrals and sequential processing creates dangerous delays. A centralized centre would also future-proof the system as Canada increasingly relies on automated risk assessment and AI-driven analytics. Technology only works if the underlying structure makes sense. At the moment, it does not.

Reform 2: Implement Continuous Vetting

Canada’s screening is largely point-in-time: we check backgrounds when applications are submitted but lack robust mechanisms for ongoing monitoring. The Eldidi case demonstrates this gap – citizenship was granted in May 2024, with authorities reportedly becoming aware of threats only in June 2024. This is also critical given that immigration applications remain “open” (i.e. additional information can be submitted by applicants) and are not necessarily locked-in for processing, until a final decision is made on an application.

Continuous vetting would:

- Monitor open-source intelligence (itself controversial, though a starting point) throughout the application process.

- Flag emerging concerns even after initial clearances.

- Enable faster response to new intelligence about existing residents (for example, alerts from foreign entities, Migration Five, or INTERPOL/EUROPOL).

- Leverage AI and machine learning to identify patterns across large datasets.

This likely requires legislative amendments to balance privacy rights with security needs, but ought to be doable if proper oversight mechanisms are established.

Reform 3: Modernize Legislative Framework

Sections 34–37 of the IRPA define security and criminal inadmissibility but were drafted over two decades ago. Modern threats – foreign interference, cyber espionage, evolving criminal codes and drug-offence classifications, and transnational organized crime – don’t fit neatly into these categories.

Parliament should update IRPA to:

- Clarify definitions of security threats to include contemporary risks.

- Establish clear thresholds for “reasonable grounds to believe” inadmissibility.

- Create expedited removal procedures for serious security threats (with judicial oversight).

- Define information-sharing authorities and limitations across agencies.

- Set service standards with consequences for non-compliance.

The recent amendments giving IRCC authority to suspend or cancel immigration documents in cases of mass fraud show Parliament can act quickly when needed. Security screening deserves the same attention.

Reform 4: Fund It

None of these reforms work without adequate resources. Current backlogs stem from understaffing at IRCC offices and visa posts, insufficient CBSA analysts, and CSIS budget constraints that limit intelligence partnerships. IRCC still accepts paper-based applications while lacking modern IT systems for database integration.

But smart consolidation offers a path forward. A unified Immigration Security Coordination Centre would eliminate duplicate screening functions, reduce redundant databases, and streamline workflows – generating savings that could fund necessary upgrades.

Strategic investment costs far less than responding to a successful terrorist attack or managing public backlash from system failures. Priorities should include upgraded IT systems for real-time information sharing, additional trained screening analysts, enhanced officer training programs, and regular quality assurance audits.

Getting the Politics Right

Immigration is politically charged, and any discussion of enhanced screening triggers accusations of discrimination. But the alternative – a system that fails to protect Canadians while creating uncertainty for legitimate applicants – serves nobody’s interests.

This isn’t about cutting immigration or targeting specific communities. It’s about ensuring that whoever comes to Canada, through whatever pathway, has been properly vetted using modern tools and coordinated processes. Most applicants pose no security risk and deserve timely processing. But the small percentage who do, require effective screening that actually works.

This means resisting both extremes: those who want to gut immigration programs entirely, and those who dismiss any screening concerns as bigotry. Canadians broadly support immigration but expect competent administration. The Eldidi case damages public confidence not because people oppose refugee protection, but because basic screening failed.

Why This Matters Now

Canada faces a critical juncture on immigration policy. Public support has declined amid housing pressures, service strains, and high-profile security failures. The federal government has already reduced immigration targets and tightened temporary resident programs. The system is under stress, and it is getting close to its limits.

Getting security screening right is essential to maintaining the broad consensus that has made Canada’s immigration system work. If Canadians lose faith that the government can distinguish between legitimate applicants and security threats, political pressure to slash immigration will intensify, harming Canada’s economic prospects and international reputation.

The solutions outlined here are practical, achievable, and consistent with Canadian values. They require political will, adequate resources, and willingness to challenge bureaucratic silos. But they’re far preferable to the status quo: a system that fails to protect Canadians while creating unnecessary hurdles for legitimate applicants.

The Eldidi arrests should be a wake-up call, not a political football. Parliament should direct the government to implement comprehensive reforms before the next failure occurs. Canada can have both generous immigration policies and effective security screening – but only if we’re willing to fix the broken system we now have.

Adam Hummel is an estates litigator at Donovan Kochman LLP and the principal lawyer at Hummel Law PC practising immigration law. His recent book, Essays From Afar: 700 Days of the Diaspora Experience Since October 7, is available on Amazon.