This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, November 27, 2025

Earlier this year, the shift in U.S. trade policy spurred Canadian governments to refocus on trade both abroad and at home. Various provinces began negotiating inter‑provincial agreements to liberalize internal trade. At the same time, the federal government has embraced the idea of moving toward a “one Canadian economy” rather than 13 separate ones.

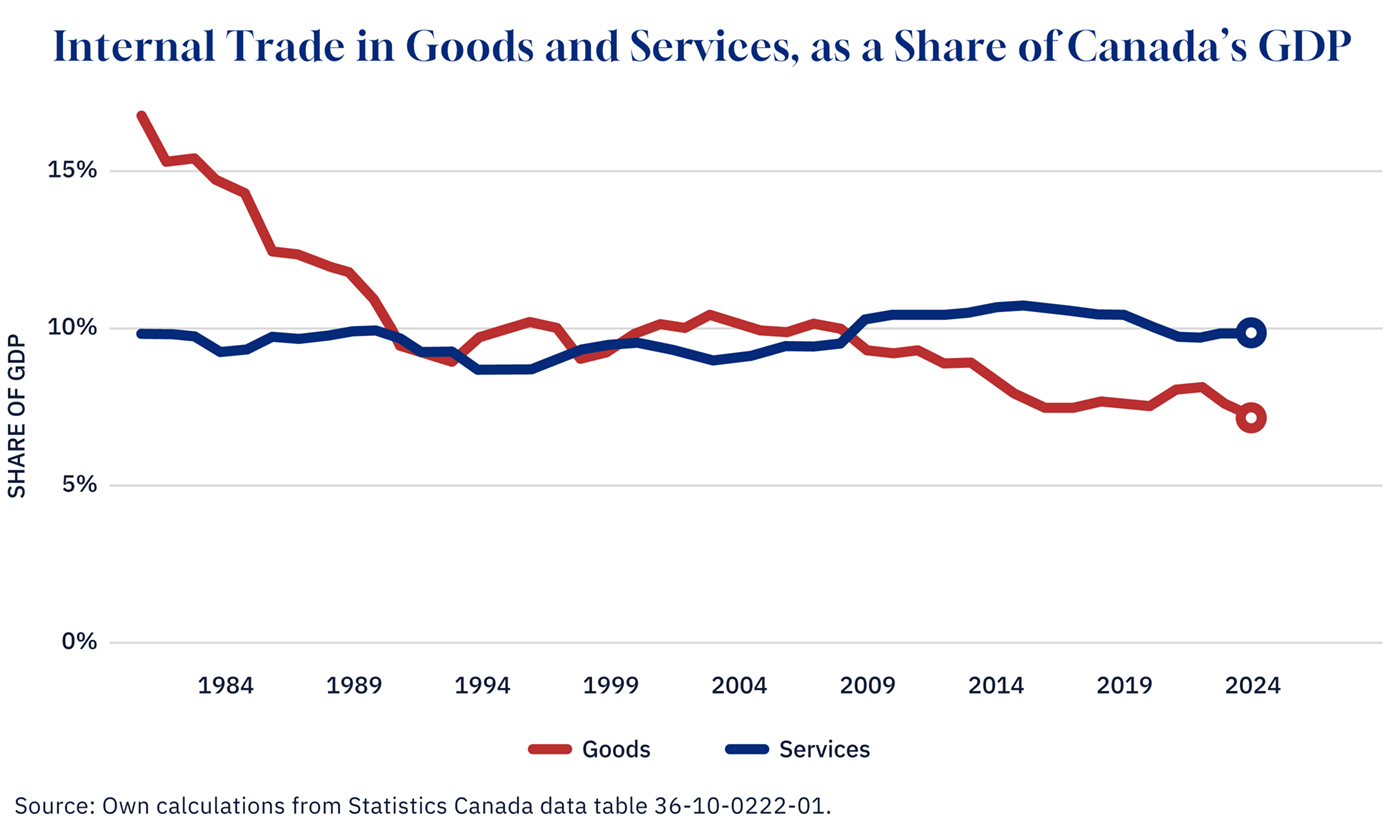

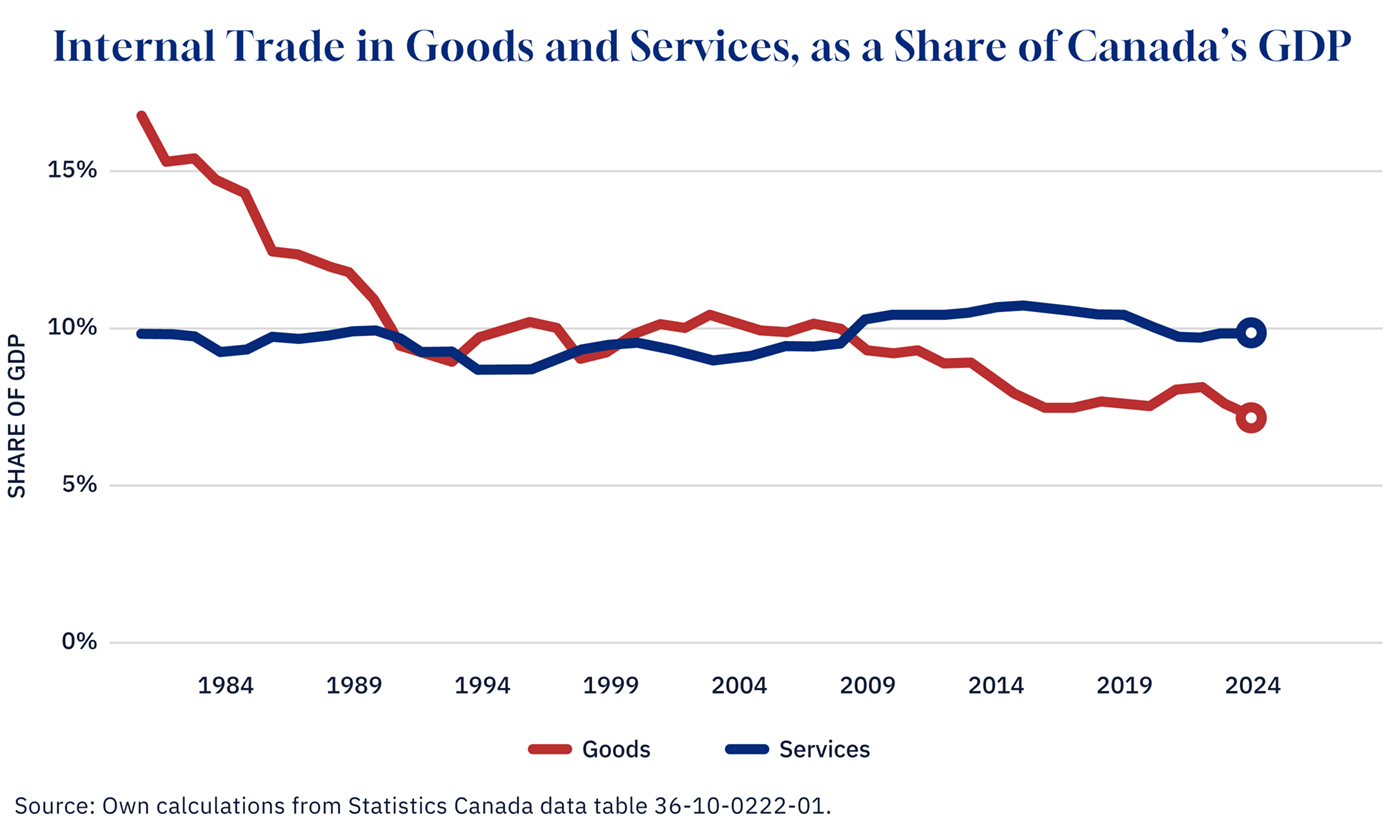

Canada’s lagging productivity adds urgency: Internal trade liberalization may be one of the more promising avenues for strengthening the economy and boosting future growth. And there’s certainly room to grow. Internal trade has reached the lowest share of Canada’s overall economy in decades.

Against that backdrop, the new agreement signed last week by federal, provincial, and territorial governments—called the Canadian Mutual Recognition Agreement—may mark the most ambitious step in internal trade policy since the Canadian Free Trade Agreement of 2017.

British Columbia calls it the “largest red tape reduction in Canada’s history.” They may be right.

Put simply, the agreement aims to ensure that a product legally allowed for sale in one part of the country can be sold in another without needing additional standards, certifications, or regulatory hoops. In doing so, it perhaps represents the fastest and most comprehensive path forward for liberalizing internal trade.

The gains on offer are significant. In a 2022 paper co‑authored by me and Ryan Manucha through the Macdonald‑Laurier Institute, we estimated that broadly applied mutual recognition could boost Canada’s productivity by as much as 7.9 percent, equivalent (at the time we wrote the paper) to roughly $200 billion per year in additional economic activity (and perhaps $250 billion today).

Does the agreement deliver those gains? The short answer: Not yet.

The agreement is a real step forward, to be sure. And the momentum this year—from governments of every stripe—is even encouraging. But significant gaps remain.

Key gaps in the agreement

First, the agreement excludes many goods where internal trade costs are most relevant—most notably food. In our paper we quantified internal trade costs across sectors: For manufactured goods, average internal trade costs were about 2.8 percent (meaning there is roughly a 2.8 percent effective cost added when goods cross provincial boundaries due to differing rules and other policy barriers).

For agricultural goods, the costs were much higher—about 9.2 percent for crop and animal production, and approaching 19 percent for products of fishing, hunting, and trapping. Moreover, interprovincial spending on agricultural goods is higher than in manufacturing, increasing the potential impact of liberalizing that sector.

To be clear, even focusing just on manufactured products (and excluding agriculture) is meaningful. Using the useful rule of thumb from our study, fully liberalizing internal trade in manufacturing might yield about $7 billion in aggregate economic gain nationwide. This could even be as high as $13 billion per year if one takes the highest end of our range of estimates.

That’s meaningful, yes, but a fraction of the often quoted $200 billion in potential gains from full mutual recognition. And even these estimates are overstatements, since manufactured food products, alcoholic beverages, and certain other items are excluded.

Provincial exemptions

Second, the agreement includes a wide variety of exemptions. Provinces and territories may list items where they wish to maintain barriers. For example, Alberta exempts beekeeping equipment, bicycle helmets, certain pressure equipment, pesticides, vaping products, and more.

The province also continues to require incoming vehicles to pass a costly inspection prior to registration—even if they were basically brand new and deemed safe in another province. (This one is, perhaps, not surprising to see, since it’s a requirement that benefits a constituency of service stations with revenue to protect.)

Other jurisdictions make similar carve‑outs: British Columbia maintains regulations on the shipment of beehive equipment and restricts certain windows, skylights, computer products, antifreeze, hearing aids, and more.

Of course, while exemptions limit the immediate scope of liberalization, they also bring an important longer-term benefit: transparency.

By requiring governments to explicitly list where barriers remain, the agreement helps shine a light on the specific frictions that continue to exist across the country. That, in turn, creates a roadmap for future reform. Indeed, past experience with the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) shows that exemptions can shrink over time, as governments reassess and remove them. This agreement might see a similar path.

What’s needed to see larger gains?

At best, the new agreement seems to tackle something like 5 percent or so of the overall internal trade challenge.

So what must be done for Canada to reach that full ~$200 billion‑type gain?

The larger share of gains from mutual recognition derives from services—and services are not covered by the agreement at all. Most internal trade is in services, and our estimates suggest that the costs involved in trading services across the country are much higher than for goods. We estimated that the average interprovincial trade cost in services was roughly three times higher than the costs facing goods.

In the service sector, provinces maintain separate requirements for professional licensing and certification, which dampens labour mobility and prevents individuals from offering services across jurisdictions. With roughly 700 provincial‑level regulatory bodies of this type, the service sector arguably represents the majority of the untapped gains.

We estimated that somewhere between two‑thirds to 95 percent of available gains from mutual recognition across jurisdictions in Canada stem from liberalization of services.

In short: The Canadian Mutual Recognition Agreement and various pieces of provincial legislation (and the broader “One Canadian Economy” project) are important steps. They mark movement toward freeing Canada’s internal market and unlocking large potential productivity gains.

Yet they are just first steps.

The momentum is encouraging—but plenty more remains to be done. Extending similar liberalization to services should be the next priority.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.