This article originally appeared in The Hub on September 2, 2025. Below are two excerpts.

Canada is no longer a reliable ally on the world stage

By Christian Leuprecht

Significant in its insignificance: this had long been the guiding principle of Canadian foreign policy in general, and Canada’s relations with the United States in particular. Since its founding, our country has invested in instruments of statecraft because a state has interests to assert. But first and foremost, we invested in instruments of statecraft to to defend our sovereignty: with “help” from the United States.

Yet, for years now we’ve let those instruments atrophy. We let our international reputation take a hit—for the sake of political expediency.

With no capabilities, we didn’t have to engage in commitments that could possibly be controversial with key electoral constituencies. There was little electoral payoff in investing in foreign policy. Doing so actually came with ample electoral liabilities.

Canada may not be conspicuous by its presence, but it sure is conspicuous by its absence. We have become significant for what we are not doing, what we are unable to do, or, to be more precise, what we are unwilling to do.

Instead of prioritizing interests, Canada’s government instead embraced a “values-based” foreign policy. In effect, it made foreign policy an extension of domestic policy, for the benefit of partisan electoral interests. In the past, Canada had effectively parlayed its interests as values: “peacekeeping” is a case in point. In recent years, however, our national interests became subservient to our values. Canada’s capabilities and commitments were displaced by Canada’s supposed “convening power.” We jettisoned instruments of power, and with it the legitimacy to convene, at the cost of the liberal international order.

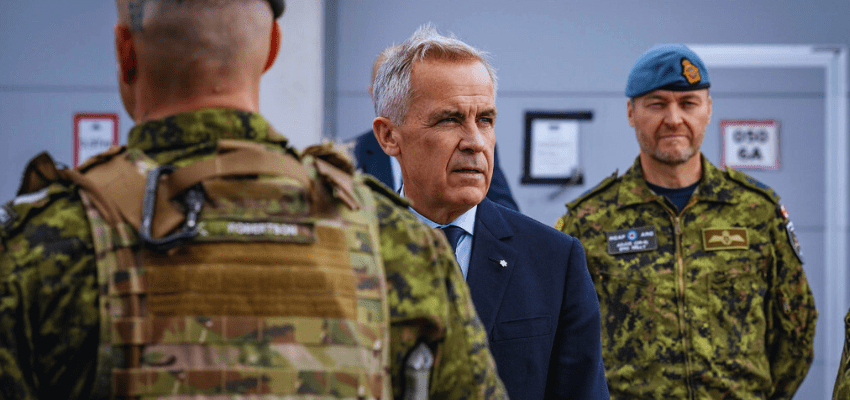

Precariously, today Canada stands isolated and alone. Tellingly, European leaders did not invite Canada to stand with them and behind Ukrainian president Zelenskyy, at the White House in August. When Prime Minister Carney showed up in Kyiv to celebrate Ukraine independence day, he did not commit to new weapons or new money. Instead, he announced…a customs agreement: with a country with which Canada has negligible trade. And Canadians wonder why allies won’t stand with us when our political and economic sovereignty comes under duress?

Political leaders tell Canadians that government needs to invest because the world has changed. The reality is that we were complacent, happy to let the world change. Privileged to retrench, Canada, and (European) allies, left the world up to the Americans. We absconded from our leadership responsibilities on the global stage. Canada failed to pay. Now, we no longer get to play.

It’s time for Canada to get back to basics: to divorce foreign policy interests from domestic policy, and to invest in instruments of statecraft that actually matter, to us, and to our allies: defence, the defence industry, and energy resilience.

Prime Minister Carney seems intent on making up for Canada’s lost decade. We better hope he can pull it off. Canada’s sovereignty, and existence, depend on it.

Christian Leuprecht is a professor at the Royal Military College and Queen’s University, editor of the Canadian Military Journal, and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute

Canada is, at last, one step closer to selecting a sub

By Richard Shimooka

Last week, the Government of Canada announced that the Canadian patrol submarine program would narrow their selection to two options for potentially 12 replacement vessels: Germany’s ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems Type 212CD or South Korea’s Hanwha Ocean KSS-III.

The announcement was not surprising: the two were the only ones that met various mandatory requirements the government had set out, including maturity of design, delivery schedule, and capability. On the latter category, the two bidders are roughly comparable, though it is likely that the larger size of the KSS-III and other features give it an edge. The real differences is when they can deliver.

Our current Victoria Class submarine fleet is in desperate need of replacement. The 35 year-old submarines operate in extremely harsh physical environments where precise safety measures must be met for them to work. Most of the class have only one or two deployments left, and it’s quite likely that the lead-boat, the HMCS Chicoutimi, may never be deployed abroad again.

As a result, the navy originally stated bidders must be able to deliver the first replacement by 2035. This would give it enough time to employ its existing personnel and leverage their institutional knowledge to aid in the transition to this new class of vessels. However, it’s likely that the navy’s original 2035 timetable is now outdated. It desperately wants to start the replacement sooner.

According to a slide shown to Prime Minister Carney during a visit to Thyssen-Krupp, the German manufacturer may be able to deliver one boat in 2034, followed by one in 2036. One of the issues with the German offer is that the 212CD has not been fully designed or manufactured—so there’s significant technical risk and that schedule may slip.

Meanwhile, in South Korea, Hanwha has stated it can deliver its first sub six years after the contract is awarded, potentially as early as 2032, and another a year after that. KSS-IIIs are already in service, with the first of an improved second batch to become operational in the coming months.

Considering these delivery timelines, it’s clear that selecting the KSS-III is far less riskier for the Royal Canadian Navy, particularly because it mitigates the consequences of an earlier-than-expected Victoria class retirement. It also means the navy can deploy a useful combat capability earlier, potentially even by 2035.

Nevertheless, there’s still a significant chance Ottawa will select the Type 212CD. The German government has lobbied hard and is clearly trying to play on Prime Minister Carney’s desire to build stronger strategic partnerships with Europe.

This will all come to a head in the coming weeks, when the prime minister decides on next steps. His government may run a more structured competition that will dive deeper into what each submarine has to offer. It could scrap the second head-to-head part of the competition entirely, and just decide to acquire the Koreans’ KS-III based on the earlier timeline.

In some ways, it’s a classic Canadian defence conundrum—does the government prefer to make a political statement that could detrimentally affect its military capability, or will it make the right decision for the Royal Canadian Navy and the country’s national security?

Time will tell.

Richard Shimooka, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.