This article originally appeared in National Newswatch.

By Tim Sargent, August 19, 2025

Canada’s security and economic future are now inseparable. The rise of aggressive powers, the changing character of warfare, and the onshoring of U.S. industries have left Canada dangerously exposed—militarily and economically. A national defence industrial strategy is essential if we are to close these vulnerabilities, rebuild our military strength, and spark the innovation and productivity growth our economy urgently needs.

Challenges and Opportunities

It has become a truism to say that the Canada—and the broader Western alliance—faces a more threatening international environment than at any time since the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, changes in modern warfare, hastened by the Russia-Ukraine war, mean that Canada can no longer hide behind its geography. The Arctic, cyberspace, and actual space itself are now all potential theatres of conflict. Meanwhile, decades of underinvestment have left the Canadian military ill-equipped to carry out even its traditional missions, with little capacity to respond to these emerging threats.

At the same time, the United States has moved aggressively to onshore its manufacturing industries, particularly in sectors such as steel and auto assembly, which threatens a Canadian economy that is already in a weak state, with declining productivity and stagnant living standards. Canada urgently needs to rethink its business model as country, particularly its dependence on assembling autos for export to the United States.

Grave as these challenges are, they also represent an opportunity. For too long, Canada has been a laggard, both economically and militarily, relying too heavily on U.S. military might and the U.S. economy. The boost to defence spending agreed upon by NATO members (including Canada) presents a generational opportunity to be taken seriously once again as a military power, while reinvigorating a sector of the economy that is innovative and highly productive.

To achieve this, we will need a defence industrial strategy that grows Canada’s defence industrial base in a way that meets our national defence objectives while also maximizing the economic opportunities for Canada. Key allies, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, have adopted such strategies, but Canada has been a laggard until now.

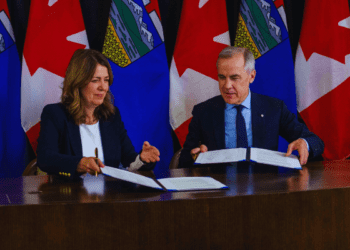

To its credit, the Carney government has recognized this gap. In June, the PM and the Minister of Defence announced $2.1 billion to lay the groundwork for a “comprehensive Defence Industrial Strategy”. The question now becomes: what should be in this strategy? What should be the objectives, and what are the elements of a plan to achieve them?

Setting the Objectives

Any strategy must begin with a thorough analysis of Canada’s defence needs and those of its allies, coupled with an assessment of Canada’s strengths as a country. We should be looking at not just traditional military equipment, but also at dual-use technologies, and key industrial inputs into the defence supply chain. Canada cannot and should not produce everything itself, and so we need to understand which key sectors we need to build up our capability in, and where Canadian industry is well-positioned to fill the gap.

Examples of where Canada could play to its strengths include:

· Ammunition, particularly artillery shells, where Canada has existing capacity and plentiful supplies of the requisite raw materials

· Drones, which, have radically reshaped the modern battlefield, as the Ukraine war shows

· Quantum technology, where Canada is a leader, and which will be a crucial weapon in cyber warfare

· Critical minerals and rare earths, which are crucial for many weapons systems, and where China has sought to dominate the supply chain

· Arctic-focused technology, such as icebreakers and under-ice drones

Canada’s defence industry needs to be integrated into these discussions from the start, and it will also be essential to avoid political wishful thinking that so often bedevils industrial policy in Canada, particularly the desire to ensure that every region has its “fair share”. Decisions must be made based on the realities of where Canada has strengths and opportunities, not on where it would be politically desirable to create jobs.

Making it happen

Coming up with a list of priorities, although not simple, is easy compared to the actual implementation. This will require a comprehensive plan with the following eight elements:

1. Reforming Procurement

Canada’s military procurement system is complex and cumbersome, with acquisition times averaging 16 years. Even something as straightforward as a pistol took 12 years from start to finish. The underlying problem is risk aversion at both the political and bureaucratic levels, which leads to blurred accountabilities and a reluctance to make decisions. Instead, processes and requirements multiply as participants try to protect themselves from criticism, ironically leading to delays and overruns that result in precisely the criticism they seek to avoid. Furthermore, the desire to prevent cost overruns means that there is an insistence on fixed-price contracts, even for new and unproven systems. This results in private sector companies either taking a pass or padding their margins, leading to significantly higher costs —precisely the outcome that policymakers are trying to avoid.

The PM’s recent announcement of a new Defence Procurement Agency with its own Secretary of State is a good start, but much more needs to be done. We need to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach to procurement. For those areas that have been designated as a priority as per the process above, we need to bring in industry at an early stage, use simplified, sole-source contracting authorities (patterned after the U.S. DoD’s Other Transaction Authority), and be prepared to share the risk with the private sector.

At he opposite end of the spectrum, where there is no compelling economic or military reason for Canada to develop its own capacity, Canada should eschew the costly and complicated Industrial and Technological Benefits (ITB) policy, under which firms who win military contacts must offset any spending abroad with equivalent expenditures in Canada, and get an acceptable product at the lowest price from whichever allied country can supply it.

More generally, requirements need to be more performance-related, with less micro-management of exact details, clearer accountabilities, and rewards for success, not just penalties for failure.

2. Increasing Access to Capital

Canadian companies across the economy have historically struggled to secure the necessary financing domestically to advance beyond the startup stage, and many ultimately relocate to the U.S. to access its much deeper capital markets. A key priority will be to prevent this from happening by ensuring sufficient Canadian-based sources of funding are available. Canada should take another leaf out of the U.S. playbook and establish an Office of Strategic Capital that would provide matching funds to Canadian venture capital funds investing in early-stage defence technology. The government should also require that the federal government’s numerous industry-facing subsidy programs at ISED and the Regional Development Agencies prioritise the defence sector, broadly defined to include aerospace and critical minerals.

The federal government should also use its financial regulatory authority to outlaw ESG policies at banks and pension funds that restrict lending to the defence sector in Canada. Unpatriotic is too mild a term to use for these sorts of restrictions.

3. Keeping Intellectual Property in Canada

As entrepreneur Jim Balsillie has repeatedly pointed out, Canadian governments can be quite naïve about the importance of intellectual property (IP). Too often, public money is used to subsidize the creation of IP that then goes to foreign multinational companies who have no obligation to use the IP to create and sustain production in Canada. Federal government financing to companies—and universities—for innovation should be conditional on a federal ownership stake in the IP created: the government can then ensure that the IP is used to develop industrial capability in Canada. In the 21st century, if you don’t own the IP, you are essentially a branch plant economy, regardless of the R&D you conduct.

4. Developing an Export Strategy

Developing export markets for our defence industry not only creates economic advantage for Canada but also helps to increase scale economies and reduce costs for our own military. While Canada has some apparent advantages in export markets—NATO countries are unlikely to source military equipment from China—we face stiff competition from countries like France, the UK, and South Korea, which also seek to bolster their domestic defence industrial base through exports, as well as the United States. The government should establish a dedicated Defence Exports Office that would collaborate with the EDC, CCC, and the Trade Commissioner Service to promote Canadian defence products in friendly countries worldwide.

5. Seeking Out Partnerships

Given the scale of resources required to invest in R&D in the defence sector, it makes eminent sense for Canada to partner with allied countries. While Canada’s recently announced participation in the EU Security and Defence partnership is welcome, it is essential not to forget that we already have privileged access to U.S. defence R&D (through the Defence Development Sharing Agreement), and that European defence technology is not always as advanced as U.S. technology—semiconductors are a good example.

Indeed, some of the most promising partnerships would be with the United States. One prominent example is the proposed “next generation missile defense shield” (the so-called Golden Dome). Whether or not this comes to pass in its entirety, the technology will find its way into NORAD systems, and Canada—which has historically paid 40 per cent of NORAD’s cost—will need to step up if it is not be seen as at best a laggard in defending North America and at worst an active threat to U.S. security. Participating now will enable our industry to contribute to cutting-edge research in areas such as space, where we have valuable insights to offer.

The biggest partnership prize would be membership of AUKUS II. Whereas the first pillar covers only submarines, the second encompasses broad technology areas, such as quantum, AI, and advanced cyber, where Canada can contribute if it is willing to pay its way and demonstrate seriousness about defence.

India-Pacific states, such as Korea and Japan, with their advanced manufacturing capabilities, are other potential partners; both countries have been building up their defence industries in recent years.

6. Protecting the Industrial Base from Foreign Threats

Canada’s defence industrial base needs to be protected against adversaries seeking to engage in espionage, acquire sensitive technology, and control (and be able to disrupt) critical infrastructure and key industrial inputs. This means a greater focus on research security in both business and academia, more stringent export controls, and tighter restrictions on foreign investment. It also means investing in cyberwarfare capabilities to prevent cyberwarfare and electronic espionage. Canada will simply not be admitted into any defence technology partnerships if we can not meet other countries’ standards of protection.

7. Improving Human Capital in Industry and Government

Ensuring that our defence industry has access to the right people will be essential. The ESDC should be directed to work with industry and provinces to ensure that the educational system—particularly community colleges—produces people with the skills to participate in advanced manufacturing. Where bottlenecks exist, IRCC should consider bringing in workers with key skills from allied countries.

Within the government, there needs to be a strategy to bring in people from industry into key positions, perhaps on secondment, who possess expertise that is not readily available in the public service. Companies would also benefit from this arrangement, as they would gain a better understanding of how the government’s internal processes work.

8. Communicating Better with Canadians

Finally, the government needs to ensure ongoing public support for defence spending, so that we can avoid the boom-bust cycles of the past and allow industry to plan for the long term. A defence public diplomacy program should be established to explain the threats and outline the strategy for addressing them. A key focus should be on the changing nature of modern warfare, including hybrid warfare, such as cyberattacks, disinformation, and economic pressure. Such a campaign could be conducted through partnerships with external research institutes that are independent of the government.

Conclusion

Firing up Canada’s defence industrial base so that it can deliver an effective military and a strong economy will not be easy. To be successful, the new Defence Industrial Strategy must take a broad view of threats and opportunities, invest in areas where we have strengths and where there are economic opportunities, and address the procurement, human resources, and financing challenges that have hindered our defence sector for many years.

But it can be done.

During World War Two, Canada was able to quickly refashion its economy to produce the tanks, planes, and ships—and the food and raw materials—that helped the allies win the war, as well as laying the groundwork for three decades of economic success.

We can do it again.

Tim Sargent is a senior fellow and the director of domestic policy at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.