This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, December 12, 2024

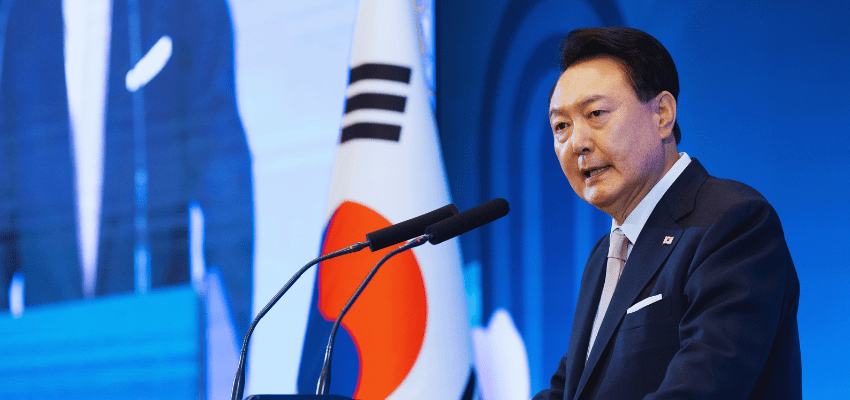

The political chaos spawned by South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol’s botched decision to call martial law should not be welcomed or celebrated. One or the other is necessary to return Japan’s closest neighbor back to a semblance of political stability.

The conundrum for Tokyo, Washington and other allies of Seoul is that the potential replacement for Yoon, opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, is likely to reverse most if not all of his foreign policy initiatives — policies that have been welcomed by friends of South Korea and supporters of an international order based on the rule of law.

To illustrate, Lee has been critical of the Yoon administration’s foreign policy toward China and Taiwan, intimating that “China was South Korea’s top export market, but now South Korea is importing mostly from China. Chinese people don’t buy South Korean products because they don’t like South Korea. Why are we bothering China? We should just say ‘xie xie’ (to China) and ‘xie xie’ to Taiwan as well. Why do we interfere in cross-strait (China-Taiwan) relations? Why do we care what happens to the Taiwan Strait? Shouldn’t we just take care of ourselves?”

This naivety about China and Taiwan is worrisome and could be very costly. Beijing is determined to unify with Taipei. It has not and is unwilling to renounce the use of force to achieve its goals. According to Bloomberg Economics, a conflict across the Taiwan Strait would cost a “staggering $10 trillion, equivalent to 10% of global gross domestic product — far outpacing the economic toll from Ukraine’s war, the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2007-2008 global financial crisis.”

With South Korea using the same critical sea lines of communication as Japan to connect its economy to the world, it would be negatively impacted by any kinetic conflict across the strait.

Lee’s positions on bilateral cooperation with Japan and trilateral cooperation between Seoul, Tokyo and Washington within the Camp David Principles Agreement is also likely to be a casualty of a change in government. Unlike Yoon, who worked to rebuild bridges between Seoul and Tokyo following the tumultuous years of the Moon Jae-in administration, Lee has labeled Japan as an aggressor country in the past and has vowed to go after historical issues and territorial sovereignty. This means returning to litigation over wartime labor issues, seeking compensation for the remaining “comfort women,” those women and girls who suffered under Japan’s military brothel system before and during World War II, and reneging on previous South Korea-Japan agreements that aimed to resolve these issues.

This is self-destructive and will not enable a potential Lee administration the ability to better the prosperity of South Korea. The goodwill and political capital accrued through Yoon’s determined diplomacy with Tokyo has enhanced mutual understanding, security and prosperity. They have accrued valuable political capital for South Korea on the global stage, embodying Yoon’s aspiration of becoming a global pivotal state.

In the case of relations with Pyongyang, Lee’s Democratic Party takes a more dovish position on North Korea, believing that the Yoon administration has provoked its northern neighbor with its focus on strengthening the U.S.-South Korea partnership, enhancing deterrence and with discussions about acquiring preemptive strike capabilities that would eliminate the leadership in Pyongyang in the case of an attack.

North Korea’s consolidation of its weapons of mass destruction program and a variety of launch systems to deter the U.S. and its allies from attacking the isolated regime will be difficult to remove even with a more dovish president in Seoul. If anything, Pyongyang has hardened its approach to the South by declaring in its revised Constitution that South Korea is a “hostile state.” Instead of seeking rapprochement with South Korea’s potential progressive leader, Pyongyang is investing in partnerships with other authoritarian states. This is evident in its provision of 5 to 7 million artillery shells and other munitions to Russia, along with the dispatch of up to 12,000 troops to fight in the war with Ukraine.

NATO and the IP4 allies (Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand), along with other friends of South Korea, are concerned that under a president who favors closer engagement with North Korea, South Korea’s efforts to support Ukraine — both bilaterally and multilaterally — may lead to less support for that country’s existential struggle against Russia’s aggression and its illegal war.

This has implications for the Indo-Pacific. Yoon has been a determined leader, having issued an Indo-Pacific strategy within months of becoming president. He also was willing to talk about the Taiwan status quo issue as a global public good and find ways to cooperate with the U.S., Japan and NATO to push back against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s might-is-right, Machiavellian approach to international affairs. South Korea even expanded its cooperation in the South China Sea to ensure that Beijing does not realize its regional ambitions of so-called lebensraum with Chinese characteristics.

It is conceivable that a potential Lee administration, with its pro-Beijing positions, may annul Yoon’s positive contributions to peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

This would be a nightmare for Japan, the U.S. and like-minded states who have worked hard to bring South Korea to the diplomatic table and make it a stakeholder in global decision-making. South Korea’s place at last year’s Group of Seven Summit in Hiroshima, in “Quad” meetings as an observer, NATO-IP4 cooperation and semiconductor relocation are all examples of the efforts friends of South Korea engaged in to demonstrate its value and importance in contributing to international order based on the rule of law.

Yoon’s ill-conceived declaration of martial law has put all this cooperation in jeopardy and is likely to usher in a new South Korean president that will be less committed to the international order that Japan and other like-minded countries depend on for peace and stability.

In many ways, South Korea may be returning to its historic alignment with China, as described in Odd Arne Westad’s book “Empire and Righteous Nation: 600 Years of China-Korea Relations.” Westad explains that Korea has long seamlessly adapted to shifts in Chinese power — from the Ming to Qing dynasties and from the Republic of China to China ruled by the Communist Party — recognizing that its economic prosperity and strategic autonomy were tied to maintaining a mutually beneficial and deferential relationship with the Asian giant.

Whether Lee falls within this world view is yet to be seen. But initial indications are that as president, he would take positions fundamentally misaligned with Japan, the U.S. and like-minded states.

The question for a potential Lee presidency is whether the logic of South Korea’s past foreign policy choices toward Beijing aligns with the reality of China and the growing concert of authoritarian states in the 21st century.

Japan, the U.S. and their allies must exercise patience and demonstrate to Lee that a global order rooted in the rule of law, strong ties with liberal democracies and support for institutions that limit the unchecked power of leaders and states serve South Korea’s best interests.

Stephen R. Nagy is a professor at the Department of Politics and International Studies at the International Christian University and visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.