By Dave Snow and Mark Harding

January 21, 2026

In recent years, a growing number of Canadians have been unsettled by court decisions that seem far removed from common ideas of justice and democratic accountability. Supreme Court Charter rulings have overturned mandatory minimum sentences for mass murderers and struck down one-year sentences for the possession of child pornography – decisions that many critics have rightly condemned as judicial activism (R. v. Bissonnette 2022; Quebec v. Senneville 2025).

At the provincial level, the trend has gone even further. Federally appointed judges in provincial superior courts have used the Charter to prevent provinces from banning drug consumption in public; requiring parental consent for schoolchildren who change their gender identity and pronouns; restricting cross-sex hormones and sex transition surgeries for minors; and closing down drug consumption sites, homeless encampments, and even bike lanes.[1] These judicial intrusions into an ever-increasing number of public policy decisions are not anomalies. They point to a deeper shift in how public policy is being shaped in Canada – one in which courts play a routine and expanding role once reserved for elected governments (Copeland et al. 2025).

As part of the Judicial Foundations Project, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI) is examining how the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has shaped Canadian political life. This commentary highlights a subtler but no less important structural way in which the Charter has changed Canadian politics: the erosion of provincial power by the Supreme Court’s creation of national rights standards. By interpreting the Charter broadly in areas of provincial jurisdiction, the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence has led to the structural loss of policy autonomy for provinces (Morton 1995).

The imposition of national rights standards by federally appointed judges has added yet another layer of national supervision to provincial policy, thereby undermining provincial diversity. Such Charter centralization has significant negative political implications. Federalism is not simply a functional division of labour between levels of government. Canadian Confederation reflected a deliberate constitutional choice to combine a federal government focused on national matters with provinces possessing meaningful autonomy to legislate, in diverse ways, across many policy domains. The slow erosion of provincial policymaking autonomy through Charter-based judicial decision-making threatens to undermine this constitutional arrangement. It may paradoxically weaken the cohesion and unity of the federation.

Thus, the Charter has produced two institutional shifts in policymaking authority: first, from the legislature to the judiciary; and second, from provincial decision-makers to national decision-makers. The fact that those national decision-makers happen to wear robes makes the shift no less injurious to Canada’s delicate federal balance. In fact, given the lack of judicial accountability, it makes it even more problematic.

The Charter of Rights is a Centralizing Document

Canadian political history has been filled with examples of the federal government seeking authority at the expense of the provinces (Vipond 1991). Formally speaking, the Constitution Act, 1867 was a centralizing document, particularly by granting the federal government the powers of reservation (delaying provincial laws for federal Cabinet approval), disallowance (vetoing provincial legislation), and the ability to appoint provincial superior court judges. Although some of this centralization was attenuated through political custom and through the decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the early 20th century (Cairns 1972), there has remained a constant tension between the federal government’s desire for uniform national standards and attempts by provincial governments to maintain regional diversity. In this environment, the provinces themselves have sought greater jurisdictional room at the expense of the federal government, most notably with respect to the administration of criminal law (Baker 2014; 2017).

Based on the experiences of other countries, in 1982 many scholars anticipated that the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter would contribute to greater centralization, whereby national rights standards would reduce provincial autonomy. By their nature, rights are universal, and therefore in strong tension with the pluralism and diversity inherent in Canada’s federation. When any federation adds a rights document to its constitution, there is bound to be friction between a national government seeking to ensure basic standards for all citizens regardless of geography on the one hand, and subnational governments attempting to preserve policy autonomy and cultural diversity on the other.

The entrenchment of the Charter laid the groundwork for two institutional shifts: first, a shift of policymaking authority from the legislature to the judiciary, which happens when courts strike down statutes from any level of government. This shift has been widely documented by Charter critics and supporters alike and the evidence for it is incontrovertible (Greene 2007; McCormick 2015; Morton and Knopf 2000). However, the Charter also created a second institutional shift: a jurisdictional shift in policymaking authority from provincial to national institutions. Questions of rights are adjudicated according to national standards that are defined by a national institution, the Supreme Court. When the Supreme Court strikes down an election-finance law in Ontario for violating the Charter, for example, this has the effect of rendering equivalent laws in other provinces de facto unconstitutional. Policy that was previously provincially defined by provincial legislatures becomes nationally defined by a national judiciary. The power and influence of this dynamic is magnified because Canada’s federal government has a monopoly over the selection of the judges who sit on federal courts, provincial superior courts, and the Supreme Court of Canada – something that provinces unsuccessfully sought to change in the 1987 Meech Lake Accord (Sigalet and Snow 2025, 522).

As a result, many expected the Charter would be centralizing. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had been open about the unifying effect of the Charter, and concerns over centralization were present during the patriation debates and committee hearings preceding the Charter’s formal entrenchment (Dodek 2018; Russell 2004, 111; Sigalet and Snow 2025). Peter H. Russell, one of Canada’s most respected constitutional experts, predicted the Charter would have a centralizing effect insofar as the Supreme Court would act as “a kind of national Senate reviewing the reasonableness of provincial laws and policies” (Russell 1983, 42). Assessing the first decade of Charter jurisprudence, F.L. (Ted) Morton claimed the net result had been “a structural loss of policy autonomy” for the provinces (1995, 183). Morton’s argument came to be known as the “centralization thesis.”

There is a rich comparative literature showing that a constitutional bill of rights, particularly when interpreted by a nationally appointed judiciary, tends to enhance the influence of the centre at the expense of the periphery. Studies have shown how nationalized processes of judicial administration and federal power over appointments can produce a “net centralist/nationalist bias of federal high courts” (Bzdera 1993, 24), as national officials seek to constitutionalize rights to preserve their policy legacies against “recalcitrant state actors who hamper national political goals” (Whittington 2005, 586; see also Hirschl 2004 and Shapiro 1981). This is especially true in a regime of “strong form” judicial review such as Canada, where the judiciary has the authority to invalidate laws from all levels of government (Harding 2022, 19–22). Indeed, Section 24(1) of the Constitution Act permits Canadian courts to order a virtually unlimited set of “remedies” where they find government action unconstitutional. This includes invalidating laws, “reading in” new terms to existing laws, and other forms of statutory interpretation to ensure accordance with nationally defined rights standards. Coupled with the Supreme Court’s wide jurisdictional scope, early scholarship suggested that the centralizing potential of the Canadian Charter was large in both theory and practice.

Nevertheless, many Canadian scholars – including Russell himself – subsequently pushed back against the idea that Canada’s Charter was centralizing (Baier 2022; Clarke 2006; Hiebert 1994; Russell 1994). The strongest critique came from political scientist James B. Kelly, who cited three reasons the centralization thesis was overstated: 1) the structural features of the Charter itself, most notably the notwithstanding clause and the “reasonable limits” clause; 2) the way that the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence has given “substance to the institutional features of the document that advance federal diversity”; and 3) provincial legislatures’ ability to engage in “dialogue” by responding to judicial decisions in a way that maintains provincial diversity (Kelly 2001, 325). In his new book, Constraining the Court, Kelly builds on this final component, arguing that the “implementation gap” between Supreme Court decisions and provincial legislative responses permits provinces leeway in deciding “whether to participate in national policy frameworks” (Kelly 2024, 42).

Constraining the Court, shortlisted for the prestigious Donner Prize, has much to recommend it. In particular, it offers a nuanced understanding of the way in which legislatures, particularly Quebec’s Assemblée nationale, respond to judicial decisions. But neither it, nor the works cited above, negate the centralization thesis. Indeed, as we shall show below, there are many reasons Charter centralization remains more of a force today than it was decades ago.

Reconsidering Charter Centralization

The key question in the centralization debate ought to be: to what extent does the Charter contribute to a jurisdictional shift from provincial policymaking to national policymaking? To answer this question, it is first necessary to distinguish between three concepts: centralization, decentralization, and non-centralization:

Centralization: To make national what was once provincial. Because the Charter makes all provincial laws ultimately subject to evaluation by the Supreme Court of Canada, the Charter’s institutional structure is fundamentally centralizing.

Decentralization: To make provincial what was once national. In contrast to centralization, there are no explicitly decentralizing instruments in the Charter, though in rare cases involving federal criminal laws related to health and other areas of provincial jurisdiction (discussed below), a Charter decision can produce a decentralizing outcome.

Non-centralization: To ensure what is currently provincial remains provincial. The Charter contains one explicitly non-centralizing instrument: the notwithstanding clause. This clause permits provincial legislatures to retain policy authority over legislation that would otherwise be rendered inoperative according to judicial rights standards. However, compared to the pre-Charter status quo, provincial invocations of the notwithstanding clause result in neither an increase nor decrease of jurisdictional authority.

In attempting to show that the Charter does not promote centralization, many have tended to conflate decentralization and non-centralization. Peter Russell (1994) noted that the first decade of Supreme Court jurisprudence produced more federal than provincial invalidations of legislation; Janet Hiebert (1994, 154) argued that Sections 1 and 33 permit provinces “to promote policies that reflect community or collective values different from the priorities of other jurisdictions”; James Kelly (2001, 354–355) claimed that the Supreme Court had developed a “robust federalism jurisprudence that has facilitated provincial diversity”; Jeremy Clarke (2006) used several case studies to attest that the Supreme Court was engaged in a “federalist dialogue” that permits provincial variation; Gerald Baier (2022, 68) concluded that Charter centralization had not been “overwhelming,” as “[p]rovincial governments lose in court, but so does the federal government”; and most recently, James Kelly (2024, 301) argued that the “implementation gap” between judicial decisions and provincial legislative responses has “ensured that the centralization thesis has not borne out.”

Yet these studies do not demonstrate decentralization; at best, they demonstrate that, on certain occasions, non-centralization can occur. When the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence permits provincial variation by upholding provincial laws, this does not increase the scope of provincial authority; rather, it maintains the same level of provincial autonomy that existed before the decisions. Likewise, while there are rare examples of provincial laws that diverge with aspects of Supreme Court rulings, the evidence of genuine disagreement with judicial decisions is quite low, both at the provincial and federal level (Macfarlane 2013; Sigalet 2025). Even when provinces use the notwithstanding clause, this does not produce decentralization: provinces merely retain the policy authority they had before a judicial decision (or in the case of pre-emptive uses, an anticipated judicial decision), since the notwithstanding clause merely means the absence of judicial review with respect to certain sections of the Charter.

In fairness, there is one area of Charter jurisprudence that can lead to minor forms of policy decentralization: when the Supreme Court strikes down a criminal prohibition of an activity that, absent the prohibition, is related to health or medicine (Kelly 2001, 350–351; Kelly 2024). There are particularly prominent examples of this: Morgentaler (1988), which struck down Criminal Code provisions governing access to abortion; PHS Community Services (2011), which prevented the federal government from closing down Vancouver’s supervised drug consumption site; and Carter (2015), which struck down the criminal ban on assisted dying. In all three instances, the absence of a federal prohibition shifted regulatory responsibility onto provincial governments. However, such cases are rare, and the policy room afforded to provinces is minor: the federal government still retains the right to criminalize large swathes of the policy field, as it has with drug consumption and assisted dying.

In addition, when the federal government decriminalizes certain matters, such as cannabis possession and consumption, this can open up provincial power to regulate under their property and civil rights powers in Section 92(13) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The Supreme Court recently upheld Quebec’s state monopoly on the sale of cannabis in Murray-Hall v. Quebec (2023), but in such cases the Court is merely allowing the provinces to take responsibility for areas ceded to them by the federal Parliament. Policy decentralization emanates from the Parliamentary decision to decriminalize, not the Charter itself.

Thus, the scope for Charter decentralization is extremely limited. In the vast majority of cases where the Supreme Court strikes down a federal law, provincial jurisdiction is not enhanced. The inverse, however, is true: every time the Supreme Court strikes down a provincial law for violating the Charter, the impugned legislation ceases to be provincial jurisdiction and becomes governed by judicially supervised national rights standards.

Provincial Invalidation Rates

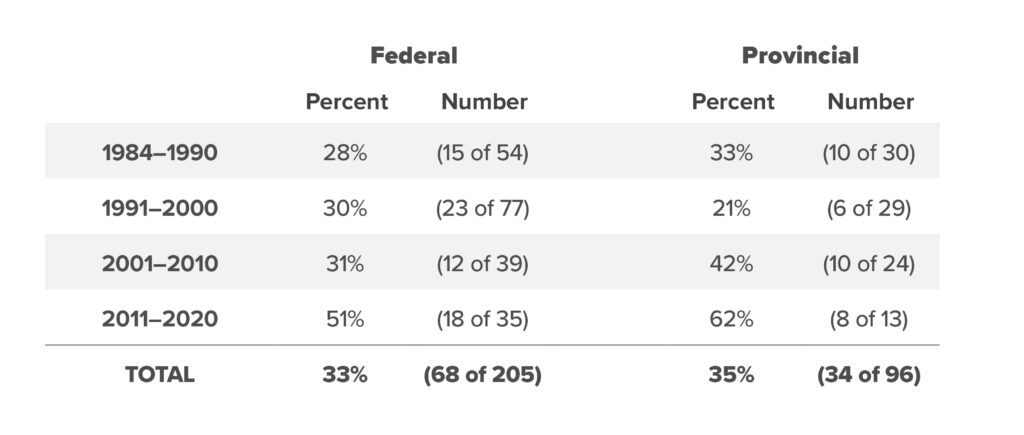

To demonstrate how the Supreme Court’s Charter decisions produce centralization, it is helpful to explore the Court’s invalidation rates. An article published earlier this year in the Canadian Journal of Political Science (for which one of us was a co-author) examined every Supreme Court of Canada decision reviewing provincial or federal legislation for Charter compliance, from its first Charter case in 1984 until 2020. In total, we coded 301 cases (205 federal, 96 provincial) to determine whether the decision invalidated the law or not, with “invalidated” including laws struck down or judicially amended in whole or in part (Sigalet and Snow 2025, 527).

Table 1 reproduces the findings from Sigalet and Snow (2025), broken down by decade. We can draw four conclusions from the data. First, the proportion of invalidated statutes for the federal Parliament (33 per cent) and provincial legislatures (35 per cent) was similar. Second, between 2011 and 2020 the Supreme Court invalidated a much higher proportion of cases at both the federal level (51 per cent) and provincial level (62 per cent) than in previous decades. Third, the proportion of provincial cases invalidated has risen the most dramatically – a near tripling from the 1990s to 2010s, from 21 per cent to 62 per cent. Fourth, while the proportion of invalidated cases has increased, the actual number of invalidated cases has not, owing largely to a decrease in the Court’s workload.

Table 1: Supreme Court Invalidation Rate of Cases, by Decade

One might be tempted to conclude that, because the invalidation rates for federal and provincial statutes both increased in the 2010s, this entails a balance between equal parts centralization (provincial laws struck down) and decentralization (federal laws struck down). However, this is a misunderstanding of how and when judicial decisions produce centralizing, decentralizing, or non-centralizing outcomes. Here it is useful to think of two hypothetical scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Supreme Court strikes down zero federal and zero provincial statutes over a period of time. Neither level of government loses institutional or jurisdictional policymaking authority. The net result is neither decentralizing nor centralizing.

Scenario 2: The Supreme Court strikes down 100% of challenged federal and provincial statutes over a period time. Provincial legislatures and the federal Parliament both suffer an institutional loss of policy-making authority, as issues that were once legislatively defined are now subject to judicially defined rights standards. However, because every invalidated federal and provincial law becomes subject to national judicial standards, only the provinces lose jurisdictional policy authority. The net result is highly centralizing.

The above data show that, from 2011 to 2020, Canada has been far closer to Scenario 2 than Scenario 1. This has resulted in a net institutional loss for both provincial and federal legislatures, but a far greater jurisdictional loss for provincial legislatures.

Examples of Charter Centralization

Another response to claims of Charter centralization has been that, while the Charter might centralize at the margins, “the nullifications have not taken place in core areas of provincial responsibilities” (Kelly 2001, 354). However, there are many recent examples of the Supreme Court invalidating or rewriting provincial legislation that are indeed in important areas of provincial jurisdiction. These include:

Collective Bargaining: In Health Services and Support v. British Columbia (2007), the Supreme Court struck down provisions of British Columbia’s law related to collective bargaining.

The Right to Strike: In Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan (2015), the Supreme Court struck down Saskatchewan’s labour law provisions preventing essential public sector workers from striking.

Pay Equity: In Quebec (Attorney General) v. Alliance du personnel professionnel et technique de la santé et des services sociaux (2018), the Supreme Court found Quebec’s pay equity law was too restrictive.

Sex Offenders Registry: In Ontario v. G. (2020), the Supreme Court struck down part of Ontario’s sex-offender registry.

Political Advertising: In Ontario v. Working Families Coalition (2025), the Supreme Court struck down restrictions on third-party political spending in the year preceding an election. Because the legislation violated Section 3 of the Charter (the right to vote), the notwithstanding clause could not be used to protect the law.

Corrections: In John Howard Society of Saskatchewan v. Saskatchewan (Attorney General) (2025), the Supreme Court struck down Saskatchewan’s correctional regulations pertaining to inmate disciplinary proceedings.

Every case outcome is an example of centralization: what was once defined by provincial legislatures is now defined by the Supreme Court of Canada. Policy decisions on how to discipline inmates, administer a sex offender registry, limit the public sector’s ability to strike, and create pay equity are now subject to national standards – not only in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Quebec, but in every province. The result is Charter centralization: a structural loss of provincial policy autonomy across a wide range of policy fields.

Conclusion

In 1983, Peter Russell anticipated that the main way the Charter would foster national unity would not be symbolic: “If the Charter is no more than a fancy document that hangs on the school-room wall, that is recited in citizenship classes and eulogized in after-dinner speeches,” Russell wrote, “I doubt that it will have a significant impact, of any kind, on the attitudes of citizens – except possibly to promote cynicism” (1983, 36–37). Russell predicted that instead, the Charter would be unifying because of judicial review: despite “disavowals of any centralizing implications of the Charter” by federal politicians such as Jean Chrétien, Russell concluded that “the centralizing tendencies of judicial review must be acknowledged” (1983, 42).

As with so much of his writing, Russell’s predictions of Charter centralization proved prescient. Yet the disavowals of Charter centralization continue – these days from scholars rather than politicians. Many of the Charter’s most prominent scholars have made misplaced comparisons between federal and provincial invalidation rates or relied on individual case studies to diminish the importance of Charter centralization. By contrast, our analysis shows not only that centralization is inherent to the structure of the Charter itself, but that the Charter’s centralizing tendencies have become increasingly more pronounced in recent years. This is further exacerbated by the implementation and elaboration of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence by federally appointed provincial courts, which have applied and extended the Court’s jurisprudence to inhibit provincial policy autonomy over everything from bike lanes to drug consumption. Coupled with federal funding for challenges to provincial laws through the Court Challenges Program (Snow and Alford 2025), there can be little doubt that the Charter continues to have a centralizing effect on Canadian political life.

Perhaps the best evidence that the Charter was intended to be a centralizing document comes from the father of the Charter, Pierre Elliott Trudeau himself. In a 1997 interview, Trudeau said:

People use the term “centralization” in an ambiguous way, collapsing the Charter’s national unity function into it. The Charter was not intended to subordinate the provinces to the federal government through judicial interpretation of the document, but to act as an instrument of national unity by highlighting what Canadians have in common, not by limiting how the provinces could act. (quoted in Kelly 2001, 354)

In this quotation, Trudeau attempts to distinguish “centralization” (a bad thing) from “national unity” (a good thing), with the latter merely a way to highlight what we have in common rather than limiting how provinces can act. On closer inspection, this distinction falls apart. The Charter acts as an instrument of national unity precisely by limiting how provinces can act. Every judicial decision that invalidates a provincial statute for violating the Charter involves the imposition of national rights standards by judges on federal and provincial superior courts whose membership is selected entirely by the federal government. With respect to the Charter, national unity is merely centralization by another name. It is a distinction without a difference.

The Charter-based shift in policymaking authority diminishes the core purposes of Canadian federalism. Provincial autonomy exists to permit democratic choice, regional variation, and policy experimentation in a country marked by profound social, economic, linguistic, and cultural diversity. When federally appointed courts impose uniform rights standards across areas of provincial jurisdiction, they reduce the capacity of provinces to respond to local preferences, replacing provincial diversity with national uniformity in areas of reasonable policy disagreement. The judicial centralization of policymaking risks undermining the very federal balance on which the cohesion of the Canadian federation depends.

In an age of judicial power, how can we prevent such centralization from occurring? The obvious answer is judicial restraint, something advocated by the Judicial Foundations Project. However, we are not optimistic that such restraint is forthcoming either from the Supreme Court or from federally appointed provincial superior court judges. Faced with an activist and centralizing judiciary, it is thus unsurprising that provincial governments are routinely turning to the one weapon in their arsenal to resist Charter centralization: the notwithstanding clause. Absent judicial restraint, we should expect its use to continue.

About the authors

Dave Snow is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. His research and teaching interests include criminal justice, public policy, and constitutional law. He currently holds a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Grant to empirically evaluate the way the Supreme Court of Canada permits reasonable limits on rights.

Mark Harding is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Guelph. He completed his PhD in the Department of Political Science at the University of Calgary. His teaching and research interests include judicial politics, bills of rights, constitutional theory, and Canadian political institutions. He is the author of Judicializing Everything? The Clash of Constitutionalisms in Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom (University of Toronto Press).

References

Baier, Gerald. 2022. “Revisiting the Charter Centralization Thesis.” In Emmett Macfarlane and Kate Puddister (eds.), Constitutional Crossroads: Reflections on Charter Rights, Reconciliation, and Change (UBC Press): 58–71.

Baker, Dennis. 2014. “The Temptation of Provincial Criminal Law.” Canadian Public Administration 57, 2: 275–294. Available at https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/9G1pDKW4/.

Baker, Dennis. 2017. “The Provincial Power to (Not) Prosecute Criminal Code Offences.” Ottawa Law Review 48, 2: 419–448. Available at https://www.canlii.org/w/canlii/2017CanLIIDocs118.pdf.

Bzdera, André. 1993. “Comparative Analysis of Federal High Courts: A Political Theory of Judicial Review.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 26, 1: 3–29.

Cairns, Alan C. 1972. “The Judicial Committee and Its Critics.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 4, 3: 301–345.

Clarke, Jeremy. 2006. “Beyond the Democratic Dialogue, and Towards a Federalist One: Provincial Arguments and Supreme Court Responses in Charter Litigation.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 39, 2: 293–314.

Copeland, Peter, Stéphane Sérafin, Kerry Sun, and Yuan Yi Zhu. 2025. “It’s the Judges, not the Charter, That Have Turned Canada into a Lawfare Nation.” National Post, October 13. Available at https://nationalpost.com/opinion/opinion-its-the-judges-not-the-charter-that-have-turned-canada-into-a-lawfare-nation.

Dodek, Adam (ed.). 2018. The Charter Debates: The Special Joint Committee on the Constitution, 1980-81, and the Making of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. University of Toronto Press.

Greene, Ian. 2007. The Courts. UBC Press.

Harding, Mark. 2022. Judicializing Everything? The Clash of Constitutionalisms in Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. University of Toronto Press.

Hiebert, Janet. 1994. “The Charter and Federalism: Revisiting the Nation-Building Thesis.” In Douglas M. Brown and Janet Hiebert (eds.), Canada: The State of the Federation 1994 (Queen’s University, Institute of Intergovernmental Relations): 153–78. Available at https://www.queensu.ca/iigr/sites/iirwww/files/uploaded_files/SOTF1994.pdf.

Hirschl, Ran. 2004. Towards Juristocracy: The Origins and Consequences of the New Constitutionalism. Harvard University Press.

Kelly, James B. 2001. “Reconciling Rights and Federalism during Review of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms: The Supreme Court of Canada and the Centralization Thesis, 1982 to 1999.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 34, 2: 321–325.

Kelly, James B. 2024. Constraining the Court: Judicial Power and Policy Implementation in the Charter Era. UBC Press.

Macfarlane, Emmett. 2013. “Dialogue or Compliance? Measuring Legislatures’ Policy Responses to Court Rulings on Rights.” International Political Science Review 34, 1: 39–56.

McCormick, Peter. 2015. The End of the Charter Revolution: Looking Back from the New Normal. University of Toronto Press.

Morton, F.L. 1995. “The Effect of the Charter of Rights on Canadian Federalism.” Publius 25, 3: 173–188.

Morton, F.L., and Rainer Knopff. 2000. The Charter Revolution and the Court Party. Broadview Press.

Russell, Peter H. 1983. “The Political Purposes of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.” Canadian Bar Review 61, 1: 30–54. Available at https://cbr.cba.org/index.php/cbr/article/view/3257/3250.

Russell, Peter H. 1994. “Canadian Constraints on Judicialization from Without.” International Political Science Review 15, 2: 165–175.

Russell, Peter H. 2004. Constitutional Odyssey: Can Canadians Become a Sovereign People? 2nd edition. University of Toronto Press.

Shapiro, Martin. 1981. Courts: A Comparative and Political Analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Sigalet, Geoffrey, and Dave Snow. 2025. “Notwithstanding Centralism: The Resurgence of the Notwithstanding Clause and the Conservative Provincial Rights Movement.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 58, 3: 516–537.

Sigalet, Geoffrey. 2025. “The Regime Politics of Responsive Judicial Review.” Constitutional Forum 34, 1: 33–42. Available at https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/constitutional_forum/index.php/constitutional_forum/article/download/29496/21487/78004.

Snow, Dave, and Ryan Alford. 2025. The Court Challenges Program: How Your Tax Dollars Fuel Social Justice Activism through the Courts. Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/the-court-challenges-program-how-your-tax-dollars-fuel-social-justice-activism-through-the-courts-dave-snow-and-ryan-alford/.

Vipond, Robert C. 1991. Liberty & Community: Canadian Federalism and the Failure of the Constitution. SUNY Press.

Whittington, Keith. 2005. “‘Interpose Your Friendly Hand’: Political Supports for the Exercise of Judicial Review by the United States Supreme Court” American Political Science Review 99, 4: 583–596.

Cases Cited

Canada (Attorney General) v. PHS Community Services Society, 2011 SCC 44, [2011] 3 S.C.R. 134. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/7960/index.do.

Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 SCC 5, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 331. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14637/index.do.

Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3. Available at https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/.

Cycle Toronto et al. v. Attorney General of Ontario et al., 2025 ONSC 4397. Available at https://assets.nationbuilder.com/cycletoronto/pages/8767/attachments/original/1753891585/Cycle_Toronto_v._AGO_Reasons_for_Judgment_PBS_July_30_2025.pdf.

Egale Canada v Alberta, 2025 ABKB 394.

Harm Reduction Nurses Association v. British Columbia (Attorney General), 2023 BCSC 2290. Available at https://drugpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Chief-Justice-Hinkson-re-Harm-Reduction-Nurses-Association-v.-British-Columbia-Attorney-General-12-29.pdf.

Health Services and Support – Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia, 2007 SCC 27, [2007] 2 S.C.R. 391. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2366/index.do.

John Howard Society of Saskatchewan v. Saskatchewan (Attorney General), 2025 SCC 6. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/20907/index.do.

Murray-Hall v. Quebec (Attorney General) 2023 SCC 10. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/19829/index.do.

Ontario (Attorney General) v. G., 2020 SCC 38, [2020] 3 S.C.R. 629. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/18563/index.do.

Ontario (Attorney General) v. Working Families Coalition (Canada) Inc., 2025 SCC 5. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/20896/index.do.

Quebec (Attorney General) v. Alliance du personnel professionnel et technique de la santé et des services sociaux, 2018 SCC 17, [2018] 1 S.C.R. 464. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/17077/index.do.

Quebec (Attorney General) v. Senneville, 2025 SCC 33. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/21250/index.do.

R. v. Bissonnette, 2022 SCC 23, [2022] 1 S.C.R. 597. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/19405/index.do.

R. v. Morgentaler, [1988] 1 S.C.R. 30. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/288/index.do.

Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, 2015 SCC 4, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 245. Available at https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14610/index.do.

The Neighbourhood Group et al. v. HMKRO, 2025 ONSC 1934. Available at https://drugpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/TNG-v.-HMK-Application-Reasons-Injunctive-Relief-JC-March-28-2025-signed.pdf.

The Regional Municipality of Waterloo v. Persons Unknown and to be Ascertained, 2023 ONSC 670. Available at https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2023/2023onsc670/2023onsc670.html.

UR Pride Centre for Sexuality and Gender Diversity v. Saskatchewan (Minister of Education), 2023 SCKB 204.

[1] Cycle Toronto et al. v. Attorney General of Ontario et al. 2025; Egale Canada v. Alberta 2025; Harm Reduction Nurses Association v. British Columbia 2023; The Neighbourhood Group et al. v. HMKRO 2025; The Regional Municipality of Waterloo v. Persons Unknown and to be Ascertained 2023; UR Pride v. Saskatchewan 2023.