By Stuart Parker, February 24, 2022

The ghost of Tommy Douglas looms large for Canada’s New Democrats. There is good reason for this. If one talks to activists in the party’s socialist caucus or in other more traditionally left-wing parts of the party, one is hard-pressed to hear a single good thing about today’s NDP or a reason to vote for the party as it is presently structured and constituted. Instead, many justify their support with its founding narrative: the decision by the Canadian Labour Congress and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation to merge into a single party under the leadership of Douglas in 1961.

Douglas is a figure presented not just as a NDP icon but as an icon of small-l liberal Canada. Although the creation of our medicare system was long and complex, and Douglas was neither premier of Saskatchewan nor prime minister of Canada when it was enacted in that province or nationally, Canada’s historiography recognizes him as the “father of medicare.”

New Democrats, from the most centrist to the most socialist, have strong incentives to style their party, the de facto “Party of Douglas.” And so they do. And they often go further, suggesting that their political choices are those the great man would himself had made, had he been in their shoes.

But this is a position they cannot take when it comes to their support for Justin Trudeau’s recent use of the Emergencies Act. The Act, a 1988 rewrite of the War Measures Act, received all-party assent from the House of Commons based, in substantial measure, on reassurances offered about the conditions under which it could and should be used. As Svend Robinson, who was serving as the NDP’s Justice Critic at the time, said on February 16:

I was in the House during 1988 debate on the Act, when we were promised that “emergency powers can only be used when the situation is so drastic that no other law of Canada can deal with the situation.” That test has not been met. The NDP can stop this. Will they?

It seems a reasonable question and one with an unambiguous answer if the party really is the Party of Douglas. Tommy Douglas, who served as NDP leader half-a-century ago, was leading the party during what historians call the October Crisis or FLQ Crisis.

In October 1970, a terrorist organization known as the Front de Libération du Quebec (FLQ), which had split from the most radical separatist party in the province in 1963, commenced an escalating campaign of attacks, including multiple bombings that resulted in several deaths, a plane hijacking, and the kidnapping of British trade commissioner James Cross, and Pierre Laporte, the deputy premier of Quebec. The FLQ then presented a set of demands and the federal and provincial governments appointed a negotiator. After three days of unsuccessful negotiations, the government of Quebec requested that the federal government enact the War Measures Act and end the hostage crisis by force.

Tommy Douglas and his New Democrats said, “no.” While the overwhelming majority of English Canada, where the NDP held all their seats, supported the War Measures Act, this was an issue of principle for Douglas.

Douglas had served as an MP from 1935-44, during which time he had seen not just the successful prosecution of a war against Germany and Japan but the abuse of war powers domestically, especially in the internment of Japanese-Canadians, something equally popular with voters but which he insisted on denouncing.

Reading excerpts from one of Douglas’ speeches at the time, some sharp contrasts are immediately obvious, not only between the leader of the NDP then and now, but between the respective crisis faced in each era:

We have agreed with the government’s refusal to accede to the outrageous demands of the kidnappers. I can understand the feelings of those sensitive individuals whose first reaction was that the government should deal with the kidnappers and should be prepared to accede to their demands.

Note that despite years of violence, and having killed three people and injured dozens more, both the Liberal government and the NDP caucus supported the negotiator appointed by the government of Quebec. It was only after the failure of three days of negotiations that the invocation of the War Measures Act was contemplated.

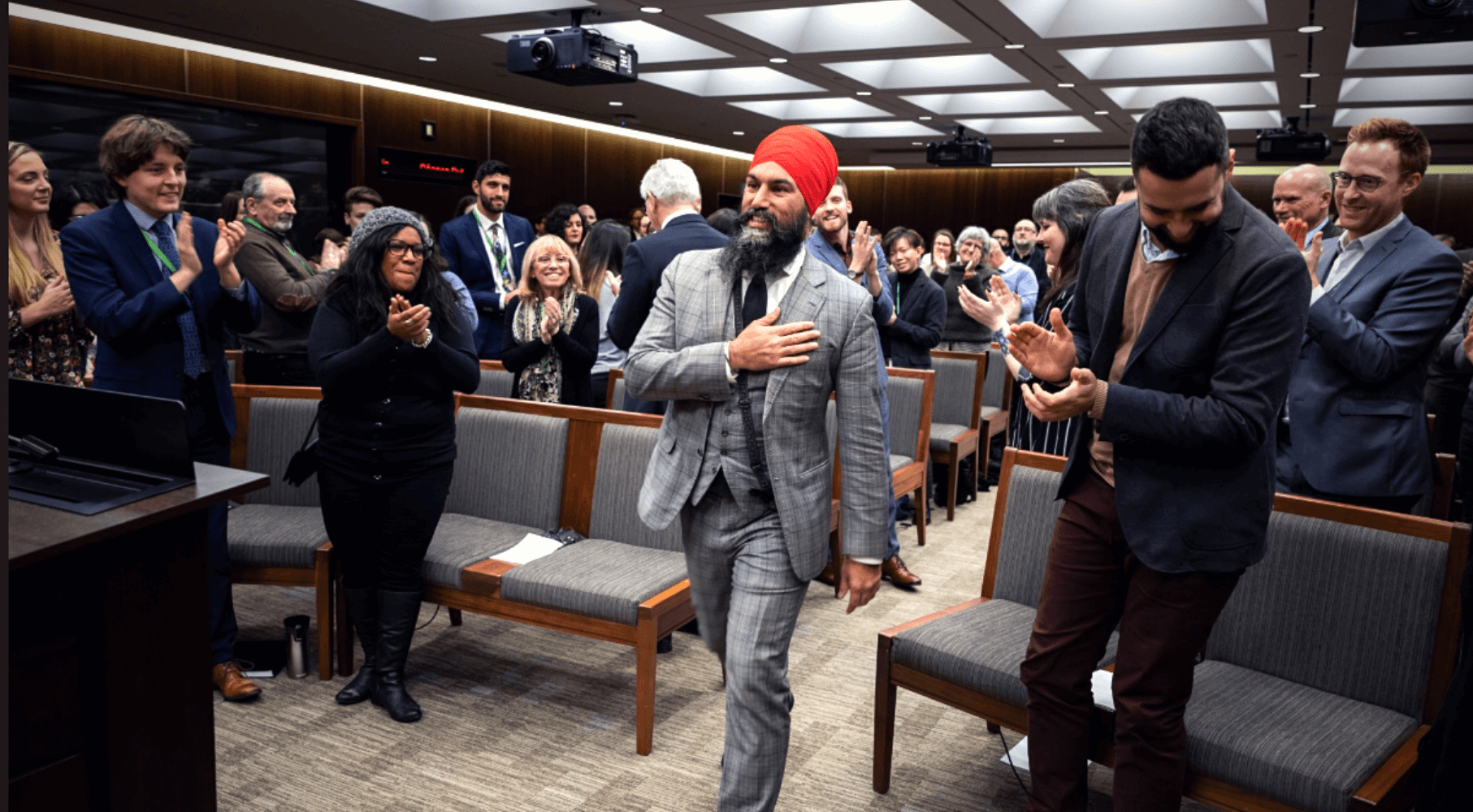

Contrast this with current NDP leader Jagmeet Singh, who at every stage backed the government’s refusal to even meet with members of the truckers’ convoy. Here we find Singh has already adopted a more authoritarian position, not just than Douglas but of the senior Prime Minister Trudeau who signed off on the appointment of a negotiator in 1970.

Douglas went on:

Now we come to a point on which we cannot support the government. The government is now convinced that there is a state of civil disturbance and anticipated sabotage which requires prompt and vigorous action.

I submit that, properly, the government had two options in dealing with the situation. The first was to deal with it under the powers which it now has under the laws of Canada…There are very considerable powers there. I think the government deserves some criticism because some of those sections have not been used.

Like Singh today, Douglas noted that no level of government had made full use of the tools already at its disposal before requesting the most powerful tool at the government’s disposal: emergency powers. But he used this argument for a very different purpose. Whereas Singh’s demand for earlier, more and harsher enforcement helped Trudeau make the case for emergency powers, Douglas saw lax enforcement for what it was and called it out: governments refraining from using the tools at its disposal in the hopes of acquiring the tools it desired more. Douglas continued:

The second option which was open to the government was that if it came to the conclusion that the powers it now enjoys under the Criminal Code and various other statutes were not sufficient to cope with this situation, the magnitude of which the rest of us are not fully aware of, the government had the option of coming to Parliament and asking Parliament, in a democratic way, to clothe it with the authority to deal with this unusual situation … [W]e would have been prepared to facilitate very quickly such matters coming before Parliament in order that the government might be able to indicate the areas in which it had not sufficient power and the justification for requiring greater powers and greater authority. But the government has not utilized this option.

Here, again, is a striking contrast between Singh and Douglas. What specific powers do you want that you do not have now? Douglas asked Pierre Trudeau. Douglas had a pretty good idea of what powers they desired and what they might be used for – and against whom they might be used. He could see that such broad powers could be used, not just against the FLQ, but Quebec separatists generally, as well as peace activists, religious minorities and counter-culturalists across the country.

And the fears and suspicions of civil libertarians like Douglas were borne-out. During the period the War Measures Act was in effect, the RCMP installed more wiretaps in BC than they did in Quebec. And it took the McDonald Commission (1977-81) and the creation of CSIS (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) as an RCMP watchdog to pare back the sweeping surveillance powers and sense of impunity unleashed by the Act in 1970. Douglas continued:

Instead, the government has taken the unusual step of invoking the War Measures Act…the government has overreacted to what is undoubtedly a critical situation. Does civil disturbance constitute apprehended insurrection? The government, I submit, is using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut. This is overkill on a gargantuan scale. Why has the government invoked the War Measures Act? May I point out that the FLQ have been around for some six or seven years. Why have we not been asked to supply the government with the powers to deal with the growing menace which it now says is so tremendous that we must invoke the War Measures Act to deal with an apprehended insurrection? The fact is, and this is very clear, that the government has panicked and is now putting on a dramatic performance to cover up its own ineptitude.

The “convoy crisis” of 2022 is simply not comparable to that faced by the country in 1970. There is no organized terrorist group. No acts of terrorism have taken place. No bombs have gone off. There are no hostages. There have been no hijackings. There is no formal list of demands beyond the vague ask of “ending vaccine mandates and pandemic restrictions.” No buildings have blown up. No one has been killed.

It is notable that even in a situation in which all those things had happened, Douglas maintained a clear, principled position: governments should not use war powers unless actually at war; and that when governments not at war require new powers that abridge civil liberties, they must come to Parliament and ask for them.

Douglas drew a line between “civil disturbance,” something that can be handled with the Criminal Code and other laws on the books, and “apprehended insurrection.” Until the government made out the case that this really did appear to be an insurrection, the government’s peacetime powers were sufficient.

The problem during the convoy crisis was not that Singh believed that Canada was facing an actual insurrection; it was that he thought war powers were a legitimate response to a mere civil disturbance. If reflective of the party at large – and there is every reason to believe this is the case – it represents fundamental shift in the values of the NDP and its leadership over the past half-century.

The concluding words in Douglas’s speech are eerily prescient for 2022:

[I]f the police in their judgment decide that some person is a member of a subversive organization – not just of the FLQ but of any organization that the police decide is subversive – or that he contributes to such a party – or that he communicates any of the ideas or doctrines of such a party – that person may be arrested and detained.

Of course, it was not just the ability to arrest and detain that the Emergencies Act unfettered, but also the ability to freeze the funds of any person deemed subversive. The precedent is alarming. What might happen, for example, not just to Greenpeace, but to its members and donors, the next time it engages in civil disobedience to block a pipeline? After all, Justin Trudeau persisted in invoking the Emergencies Act despite the fact that Ottawa and other protest locations had already been cleared of demonstrators and their trucks.

Tommy Douglas was the kind of statesman who asked those sorts of questions, who thought about the long-range implications of the overreach and abuse of state power. Although not a sympathizer with Quebec separatists, Douglas had the imaginative empathy to be concerned about the illegal detention of members of that movement. And he could also think about how the powers used against them could (and were) turned against peace activists and members of the counterculture in Western Canada.

Sadly, Jagmeet Singh is no such statesman. He was incurious about what new powers the government sought or what it might do with them. He seems incapable of observing a raucous crowd of people who disagree with him as possessing the same rights as one that does. And he seems equally uninterested in Canada’s history of abusing these powers, from Japanese internment of Japanese Canadians and the Padlock Law to the MacDonald Commission.

Stuart Parker is a Vancouver-based writer and broadcaster who serves as president of Los Altos Institute, a socialist think tank.