This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Jonathan Berkshire Miller, September 4, 2025

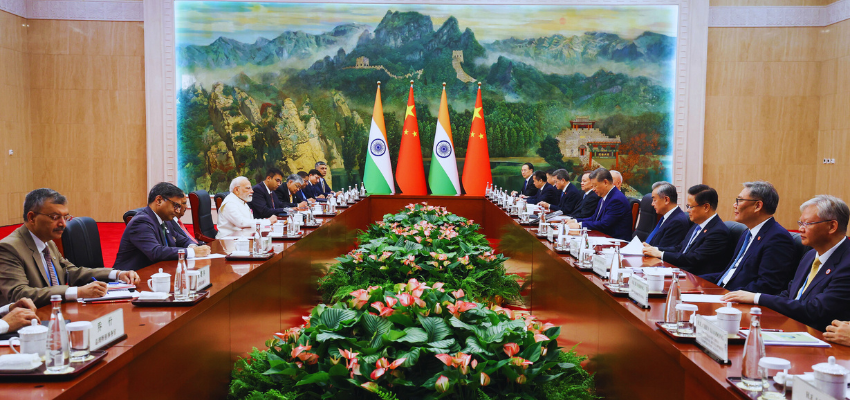

At first glance, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit this past week in Tianjin, China, looked like a thaw between New Delhi and Beijing.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first visit to China in seven years, his staged embrace with Vladimir Putin and the friendly photos with Xi Jinping all created an image of reconciliation and concern that New Delhi may be at risk of being wrested away by the emerging authoritarian axis.

For Beijing, it was an opportunity to present its leadership and a united SCO behind China’s vision of a different world order. For Moscow, it was a reminder that it still matters despite the costly war in Ukraine.

But New Delhi’s optics deserve a closer look.

Xi used the moment to unveil ambitious plans: an SCO development bank, deeper cooperation on energy and artificial intelligence, $1.4 billion in financial commitments and greater access to China’s BeiDou satellite system. It’s Beijing’s push to give the SCO more institutional weight and position as an alternative to the U.S.-led order. Modi’s presence gave those plans a veneer of legitimacy — even though Sino-Indian ties are still riddled with mistrust and border tensions.

India, however, played a subtler game. New Delhi again refused to endorse the Belt and Road initiative, the SCO’s signature China-backed project. Russia, Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian states voiced support; India did not.

The reason is simple: BRI’s flagship, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, passes through territory that India claims. Backing BRI would have meant abandoning a long-held principle of sovereignty. That steady refusal shows that beneath the warm gestures, deep suspicion remains.

Modi’s attendance should also be viewed against worsening ties with Washington. U.S. tariffs on Indian steel and aluminum and a more transactional trade stance have strained what many hoped would be a cornerstone of the Indo-Pacific order. As U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called the summit “largely performative,” the pictures of Modi with Xi and Putin nonetheless carry weight in Washington. In that light, Modi’s actions signaled both India’s independence and a warning that New Delhi won’t be ignored.

There are, however, hard limits to any improvement with China. Repeated crises along the Line of Actual Control that divides the two countries in recent years have damaged trust. Even as both sides look for ways to disengage, they haven’t resolved the deeper differences over power and intent. China hasn’t shown it’s ready to treat India as an equal in Asia and India isn’t prepared to sacrifice its interests for China’s aims. Modi’s Tianjin remarks — calls for counterterrorism cooperation and veiled warnings about double standards — were aimed partly at Pakistan and partly at a domestic audience to underline that sovereignty matters.

So, India’s moves at the SCO were neither a tilt toward Beijing nor a retreat from the West. They showed the balancing act that defines Indian strategy: Engage but remain cautious. The hug with Putin reminded everyone that Russia is still seen as a useful partner (as abhorrent as it is to many of us in the West) in New Delhi, even as it grows closer to China. The smiles with Xi acknowledged the need to keep talking, not to suddenly rebuild trust. And saying no to BRI made clear that India still has red lines.

That balancing act, however, has risks. To China and Russia, India’s presence strengthens the SCO as a counter to the West. In Washington, it can look like drift. In reality, India is trying to keep its options open — asserting independence, using multilateral forums and avoiding binary choices in a new Cold War. But this flexibility comes at a cost. U.S. tariffs, an assertive China and Russia’s growing reliance on Beijing all narrow India’s room for maneuver.

Still, India isn’t ready to drop its balancing act. Rejecting BRI wasn’t mere symbolism; it was a firm statement that India won’t trade sovereignty for diplomatic ease. The handshakes and smiles in Tianjin may ease the temperature for a while, but they won’t heal deeper wounds.

For Japan and other Indo-Pacific partners, the takeaway is clear: India’s diplomacy is pragmatic and self-interested. Engaging China in multilateral settings doesn’t equal trust — it’s recognition that interaction is unavoidable in today’s unsettled world.

The SCO summit exposed a central tension in India’s foreign policy: a desire to be everywhere but not tied down. That necessity-driven flexibility brings advantages, but it also blurs India’s message. Whether this balancing act can hold as U.S.-China tensions rise is unclear. What Tianjin made most evident is that India will keep following its own path — cautiously, one handshake at a time.

Jonathan Berkshire Miller is a co-founder and principal of Pendulum Geopolitical Advisory and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa