This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, February 19, 2026

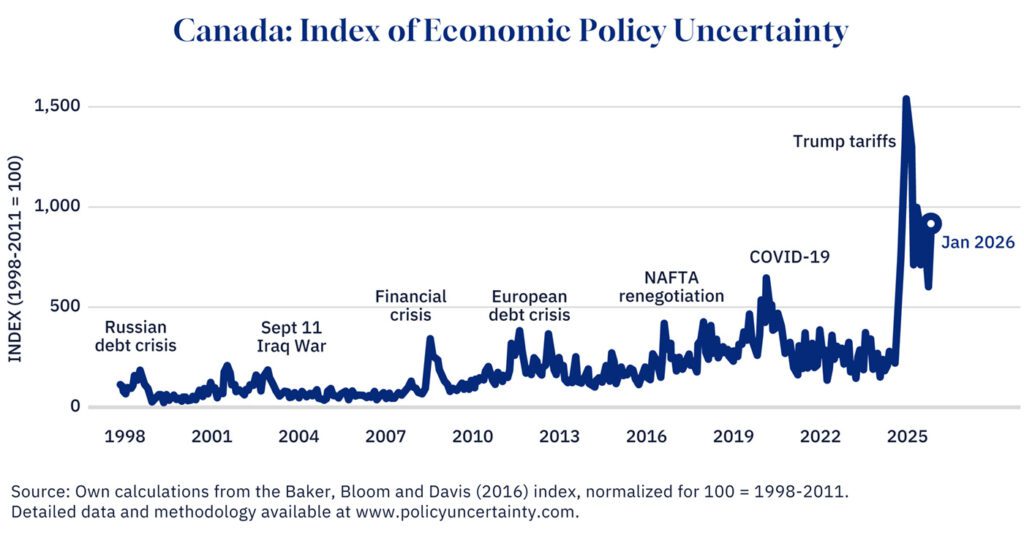

Last year, uncertainty was a major theme in Canada. Frequent and dramatic changes in U.S. trade policy kept people, businesses, and governments on edge. If that level of uncertainty had lasted, it could have triggered a recession.

But as 2025 unfolded, conditions turned out better than many anticipated. Some trade tensions with the United States eased, and policy uncertainty fell sharply from its earlier highs.

Lately, though, uncertainty has been going up again, with one key measure rising by more than 50 percent in January compared to the month before, which was already higher than the worst point in the pandemic.

This matters for the strength of Canada’s economy and for the number of jobs available to Canadians.

This experience also holds lessons for those supporting separatism in Canada (however real their grievances may be with current arrangements), simply as a supposed costless protest vote. It isn’t. There are real and significant hidden costs of political uncertainty.

What the data show

Many have discussed how uncertainty hurts jobs, investment, trade, and more.

And the effects can be quite large. In 2025, high uncertainty may very well have cost tens of thousands of jobs.

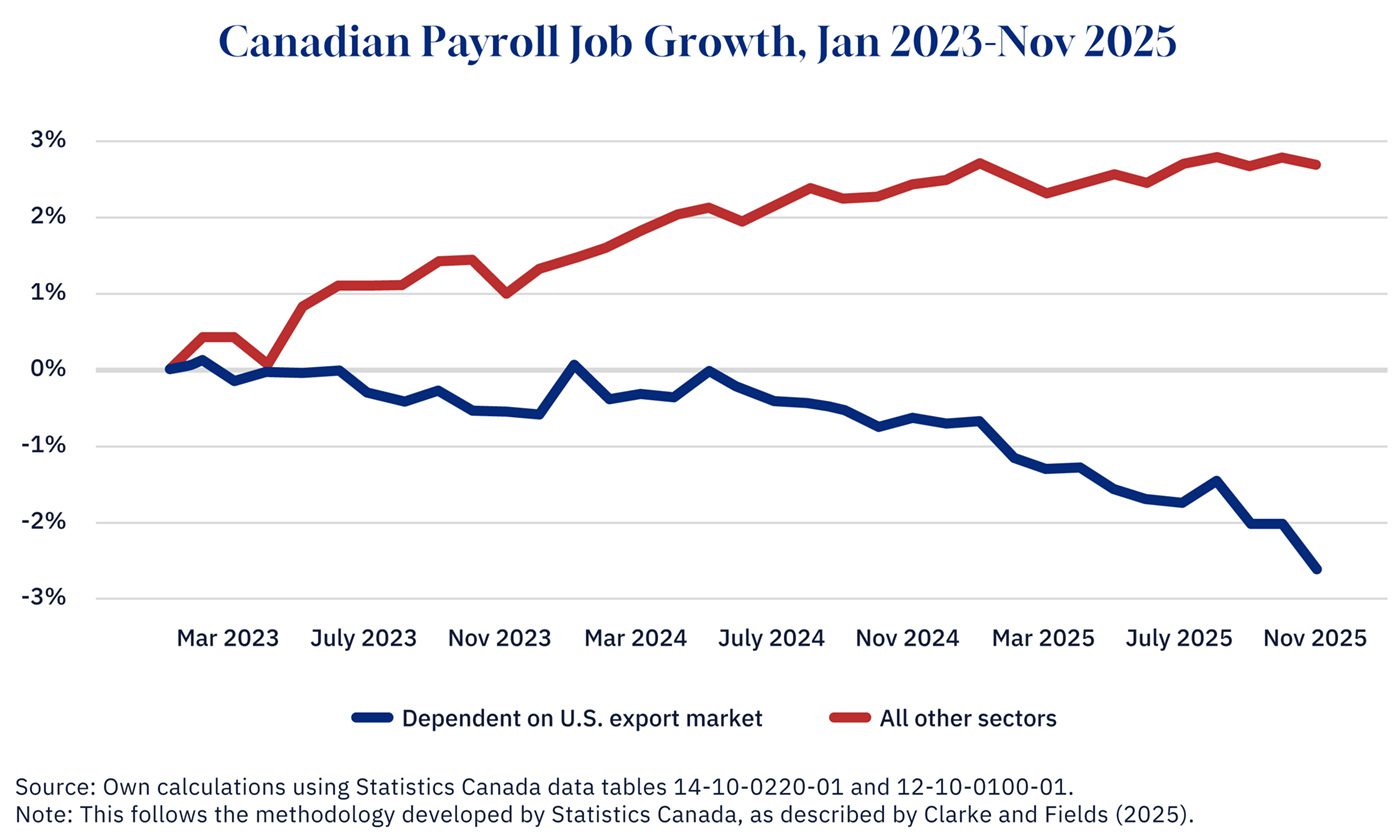

To shed light on this, Statistics Canada researchers Sean Clarke and Andrew Fields compared sectors that depend heavily on U.S. demand for Canadian exports with all other sectors in the economy. They focused on industries where more than 35 percent of jobs rely, directly or indirectly, on exports to the U.S.

They found that employment in U.S.-dependent sectors declined by nearly 18,000 between December 2024 and August 2025, while the rest of the economy experienced growth. Importantly, these job losses were not driven by an increase in layoffs. Instead, they reflected a decline in hiring. Exactly as one would anticipate, businesses regularly cite uncertainty as the top concern they are responding to.

Updating and extending their analysis, I find that payroll employment in sectors dependent on U.S. exports has declined by 2.7 percent since the beginning of 2023, equivalent to more than 45,000 jobs, with most of the decline following the U.S. presidential election. Over the same period, employment in the rest of the economy has increased significantly.

Had payroll employment in U.S.-dependent sectors grown at the same pace as the rest of the economy, I estimate total employment in Canada would be nearly 91,000 jobs higher as of November.

The largest declines are in truck transportation, motor vehicle parts manufacturing (subject, it must be said, to real tariffs and not just uncertainty), clothing manufacturing, seafood products, and more. Motion picture and video production has also seen considerable losses, and it was not long ago that President Trump threatened to impose 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made movies.

In total, the decline represents roughly 0.5 percent of all jobs in Canada. While that may seem small, it accounts for nearly one-third of the overall decrease in Canada’s working-age employment rate over the same period.

Uncertainty is clearly a problem.

The lesson for Alberta

There is a lesson here, particularly for those in Alberta who support a separatist referendum merely to express (often legitimate) frustration with how Canada has been functioning.

Trade-related uncertainty can originate domestically just as easily as it can from policy changes abroad. As I have written before, separation could increase the cost of interprovincial trade between Alberta and the rest of Canada. That would have long-run consequences for productivity and living standards.

In the shorter term, it would create risks for jobs currently supported by provincial exports.

A common counterargument I received following those pieces was that an independent Alberta might join the U.S. Given the higher level of productivity in the U.S., closer integration could raise living standards by more than enough to offset increased trade costs with the rest of Canada. That is a valid point.

But many who might support separation, or may vote that way in a referendum, do not necessarily favour independence or becoming a U.S. territory. For some, potentially as high as half of supporters, a vote for separation may be a way to express frustration with federal policy rather than a genuine desire to establish a new country.

For those individuals, it is important to recognise the uncertainty such a vote would create comes with potentially significant costs for their fellow Albertans.

Even the prospect of separation would raise questions about future trade relationships. Businesses operating between Alberta and the rest of Canada would face new risks. And if there were a successful vote, the nature of any post-referendum negotiated outcome would be unclear. Until those uncertainties were resolved, there would be real economic costs. Even a failed vote, there would be lasting uncertainty if the “leave” side saw a non-trivial vote share.

How large could the effects be?

Using the same approach developed by Statistics Canada to measure trade exposure, I estimate that approximately 900,000 Albertans work in sectors where at least 35 percent of jobs depend, directly or indirectly, on exports to other provinces or abroad. If an uncertainty shock similar to the one Canada recently experienced were to occur in Alberta, job losses would be on the order of 50,000.

Even focusing only on interprovincial trade, the exposure is significant. I estimate that roughly 200,000 Albertans are employed in sectors where at least 35 percent of jobs depend on exports to other provinces. If uncertainty reduced hiring across those sectors by a comparable amount, that alone could mean more than 10,000 fewer jobs.

These figures simply illustrate potential orders of magnitude and should be taken with several grains of salt. But the broader point is undeniable: uncertainty significantly affects how businesses invest and hire.

Canada is currently coping with uncertainty driven by policy changes south of the border. But uncertainty created by our own actions can be just as costly.

Those who view separation as a costless protest vote should consider these effects carefully and, perhaps, explore other avenues to advance their concerns.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.