This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, December 11, 2025

This isn’t temporary either. It’s the start of a new era—one that will shape economic outcomes and policy choices for decades. The sharp turn in U.S. foreign policy raises fundamental questions for Canadian security.

But many other challenges are closer to home: rising uncertainty and the restructuring of global production, widening regional divides, a decades-long productivity problem, and mounting fiscal pressures that limit what governments can do. Each deserves a closer look.

Trade and the new uncertainty

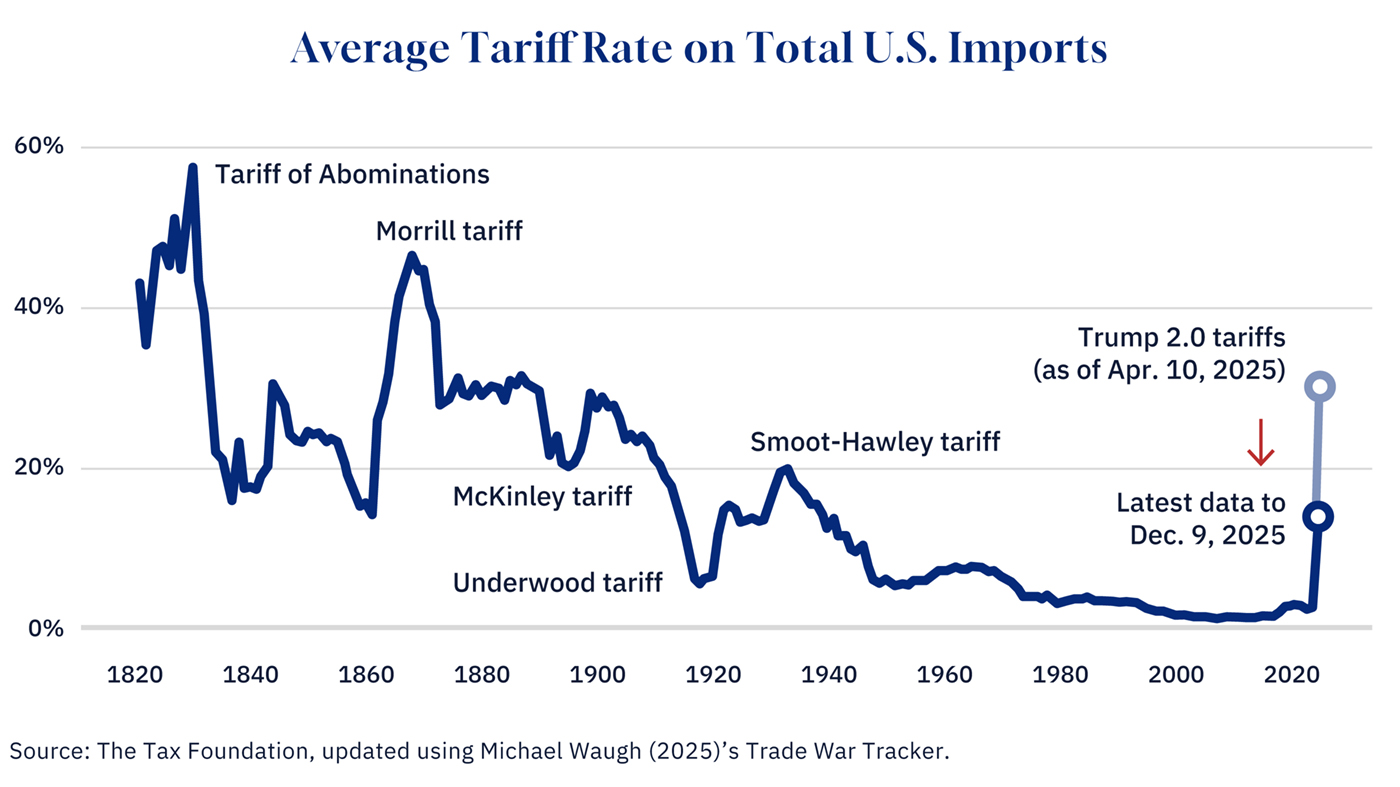

Earlier this year, the U.S. considered tariff increases that would have pushed average import duties to levels not seen since the 19th century. Most weren’t implemented as announced. Some were softened. Some were delayed. But U.S. tariffs today are well above where they were a short time ago.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

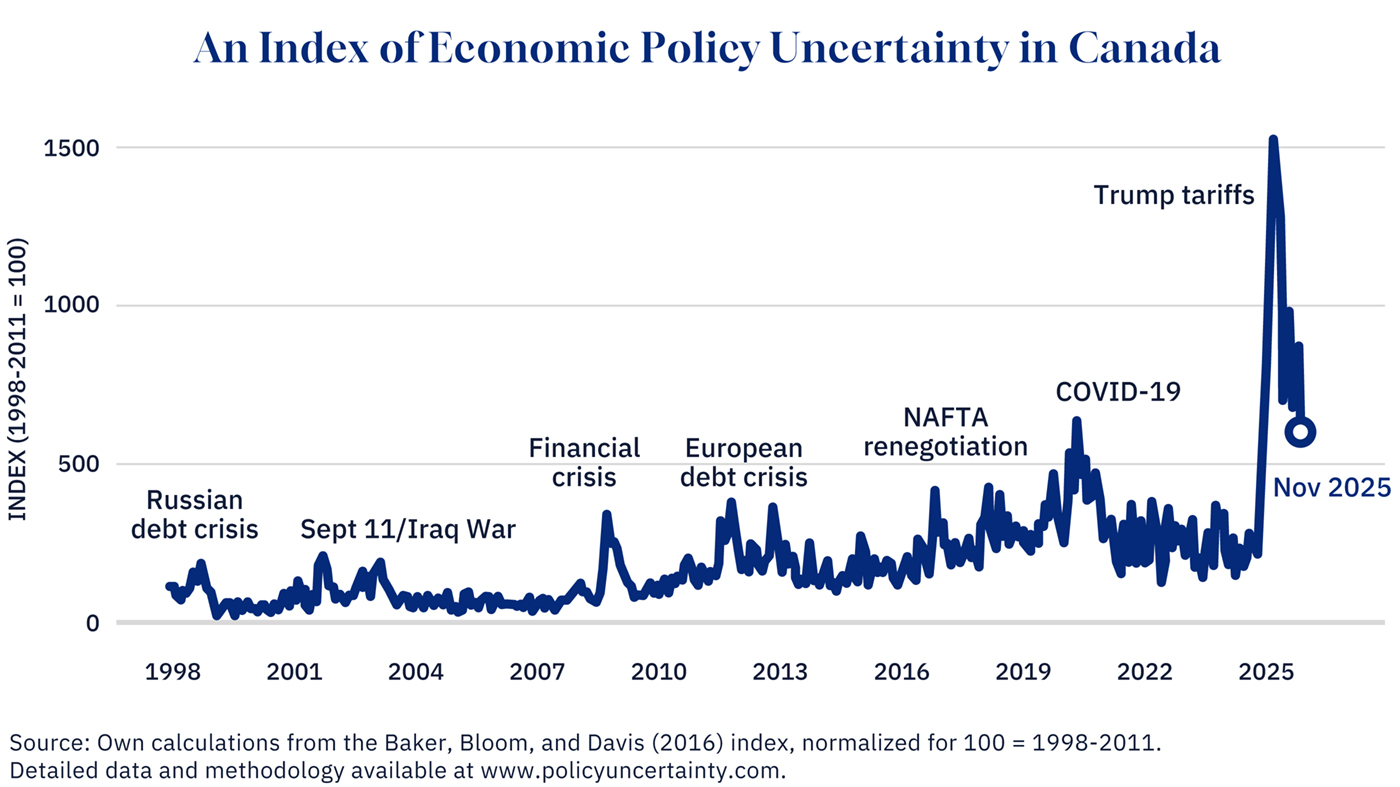

Canada has fared relatively well. Our average tariff rate into the U.S. remains low, thanks to our trade agreement. But the biggest shock isn’t from the tariffs. It’s the uncertainty—something we haven’t experienced in decades.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Even if U.S. trade policy reverts to where it was, the damage is done. Firms making long-term decisions will now factor in different risks. Supply chains will be built to reduce exposure to sudden policy shifts. That means more redundancy, higher costs, and lower productivity.

Growing regional divides

This new global uncertainty collides with another major shift: growing economic divergence across Canada’s provinces.

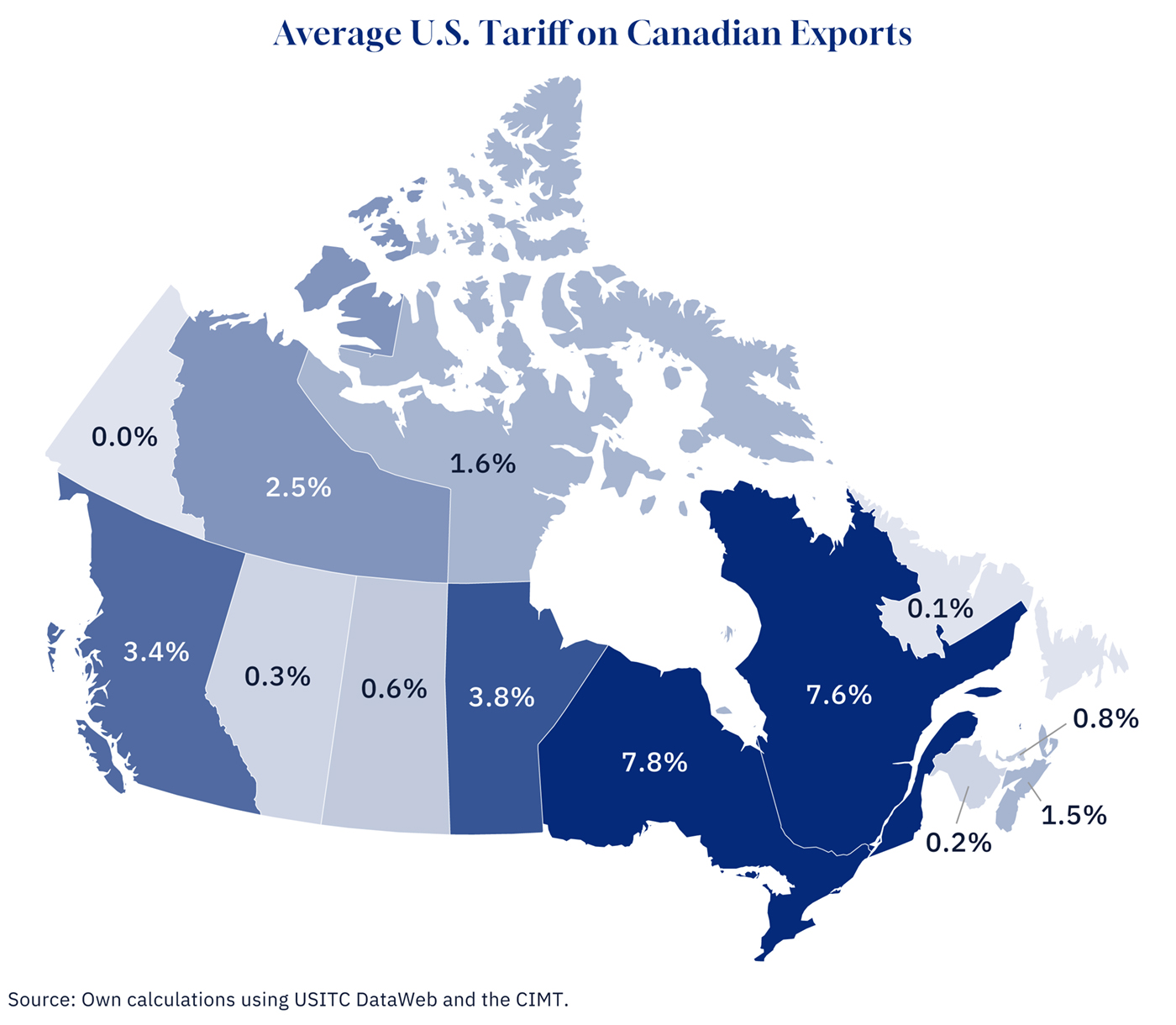

The trade shock makes this clear. Tariff exposure varies sharply by province. Some parts of the country are barely affected. Others face much larger hits. Estimates suggest meaningful losses to output in Ontario and Quebec from tariffs alone, even before accounting for how uncertainty affects investment.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Canada’s regional economies have been drifting apart for decades. Energy-producing regions follow different cycles than manufacturing provinces. Population growth, housing pressures, and labour market conditions also vary widely.

The challenge for federal policy is obvious. When economic conditions differ more across regions, uniform policy responses become harder to justify and less effective. A single national approach will increasingly miss the mark in some regions while overshooting in others.

This doesn’t mean abandoning national objectives. But it does mean shifting toward more tailored approaches and greater flexibility in federal-provincial arrangements. The recent Alberta-Ottawa MOU is one welcome example of this shift.

The productivity gap

Layered on top of all this is the biggest long-run challenge: productivity.

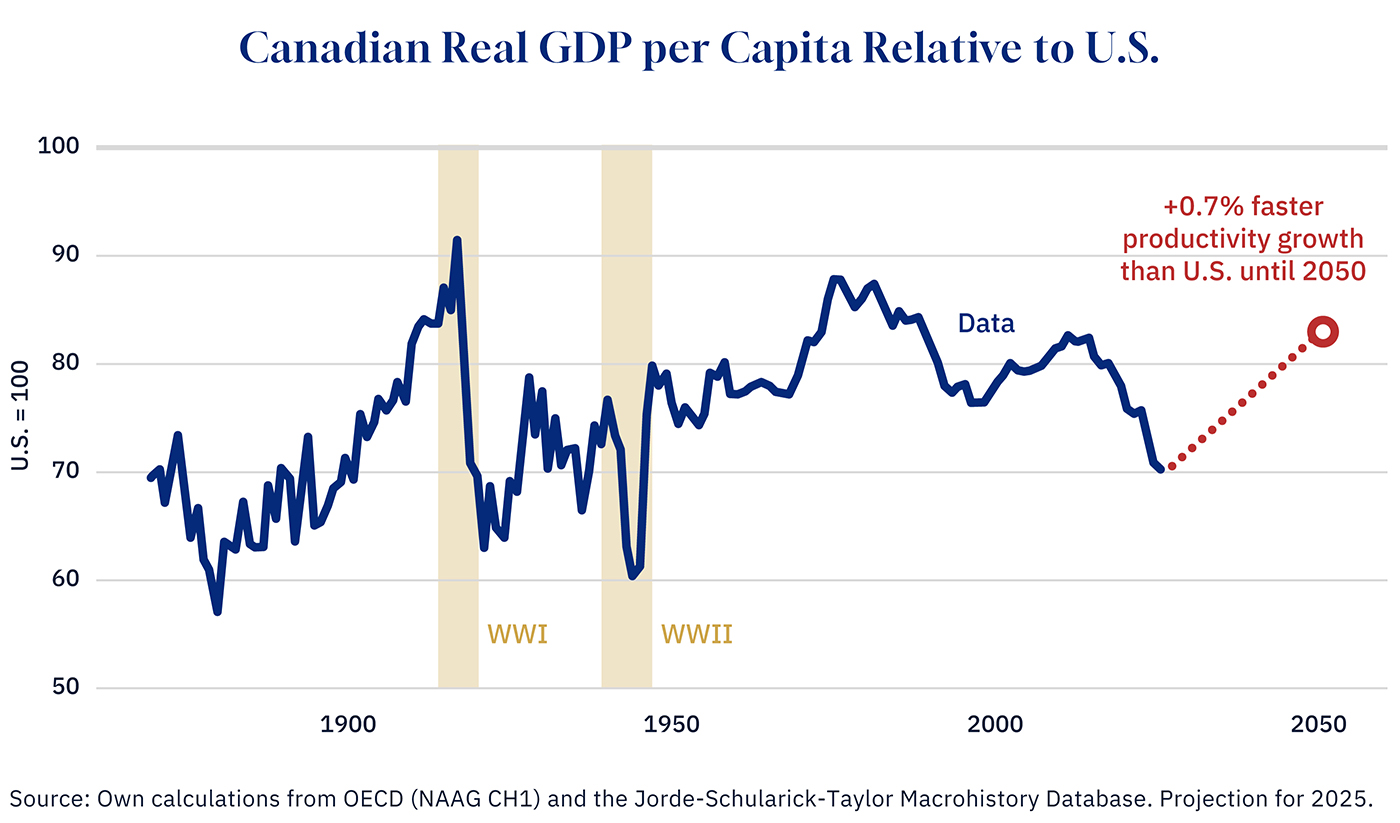

Over the past decade, Canada’s labour productivity growth has fallen well behind the U.S. and other advanced economies. Had we simply kept pace with our earlier trajectory, Canada’s economy today would be roughly 20 percent larger—that’s well over $600 billion in foregone annual income. That gap dwarfs the estimated impact of even a severe trade war.

The scale of this problem is enormous. Closing it won’t happen in one budget cycle or even one decade. Even optimistic scenarios suggest it would take until mid-century (or more!) to regain the ground lost over the past decade.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Overcoming this will be a generational challenge.

Mounting fiscal pressures

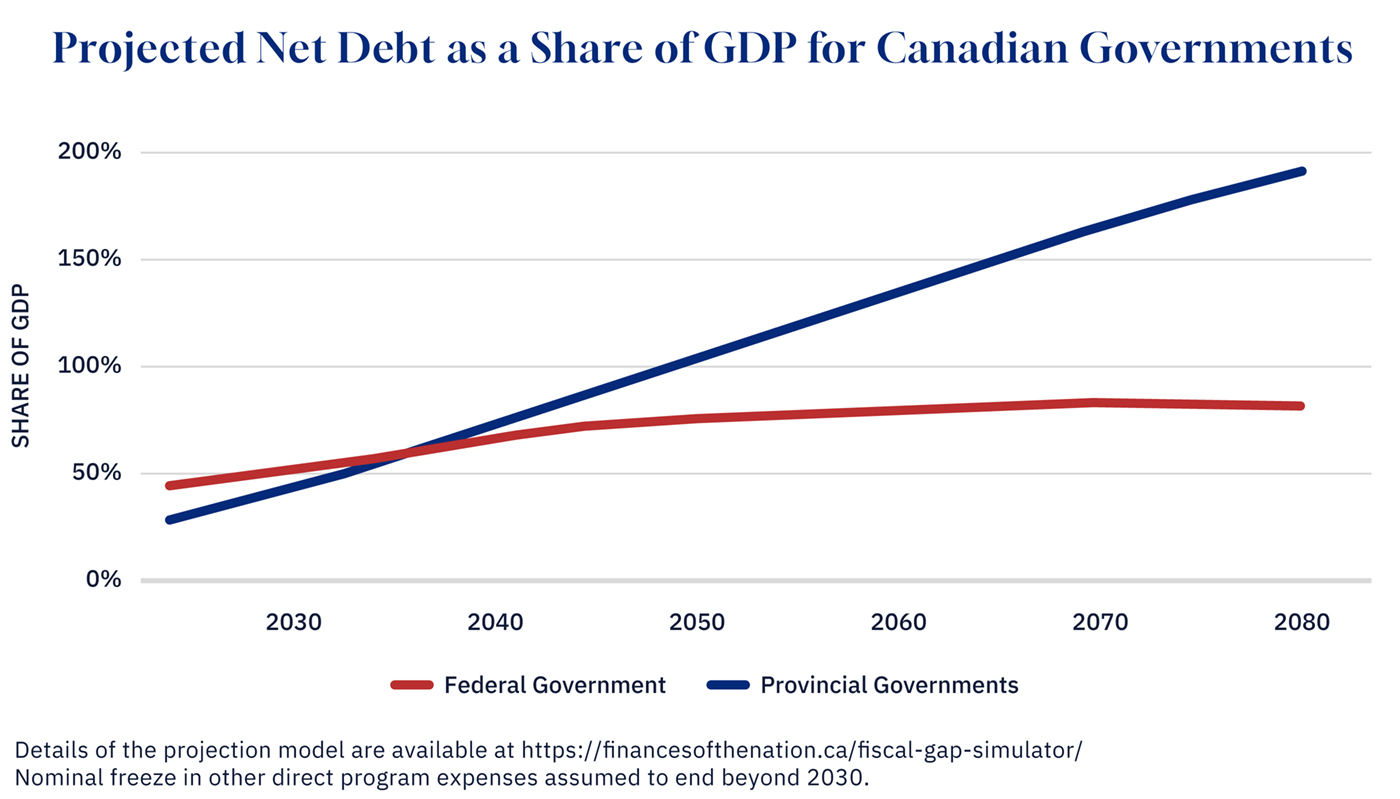

All of this is happening against a tightening fiscal backdrop, especially at the provincial level.

Population aging and health care pressures are now driving provincial budgets. Long-run projections show large and growing gaps between revenues and spending, driven primarily by health costs. Closing those gaps will require higher taxes, slower program growth, or both. Even large, higher-income provinces like B.C. are in dire straits.

In the past, there was an implicit assumption that the federal government could provide relief through higher transfers, new shared-cost programs, or financial support. That assumption is far less secure today.

Federal fiscal capacity is much more constrained than it once was. Rising interest costs and defence spending increases leave Ottawa with limited room for new permanent obligations. The federal government is far closer to its own fiscal limits than many Canadians realize, especially after abandoning its fiscal anchor in the last budget—something the IMF has already raised concerns about.

In fact, according to the government’s own estimates, federal debt-to-GDP may flatline over the next two decades. But that projection doesn’t include military spending increases. Add that in, and debt rises significantly.

Federal finances are on a knife’s edge between sustainable and unsustainable, so provinces will increasingly be on their own.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

The value of provincial experimentation

That reality makes provincial autonomy and experimentation more important than ever.

Faced with large fiscal pressures and less help from Ottawa, provinces will need to explore different approaches to service delivery, revenue structures, and policy design. Health-care reforms (like some big moves in Alberta recently) are especially valuable, given that’s where pressures are most acute.

The value of experimentation is simple: provinces can learn from each other. When one province tries a new approach and it works, others can copy it. When something fails, the rest of the country avoids that mistake. This kind of policy learning matters more when budgets are tight and the stakes are high.

Gone may be the days of national health accords like Paul Martin’s “fix for a generation.” Rising federal involvement in provincial areas may be over, too.

That’s not a failure of federalism—it may simply be what the new era looks like. When both orders of government face tighter budgets and regional economies diverge, the path forward likely requires more flexibility, not less.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum