This article originally appeared in Japan Up Close.

By Stephen Nagy, February 13, 2023

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24th 2022, has demonstrated that a might-is-right, Machiavellian approach to foreign affairs is still seen as a legitimate way to engage in international relations by authoritarian states. The downstream effects of the invasion include higher energy prices and a disruption in supply chains contributing to global inflation, food insecurity problems as well as increased instability in the Global South. It has become clear that we can no longer disconnect different regions of the world from the idea of preserving, protecting and investing in a rules-based order.

For Japan, Russia’s invasion is a preview of the disruptions that could come in its backyard. China continues to challenge the rules-based order in sea lines of communication (SLOCs) in the South China Sea (SCS), the Taiwan Strait, and the East China Sea (ESC). Collectively, all of these are critical arteries that transport approximately 5.5 trillion US dollars in imports and exports annually. They also transport critical energy resources that fuel the Japanese, Chinese and the South Korean economies that are key engines of economic growth for the Indo-Pacific and global community.

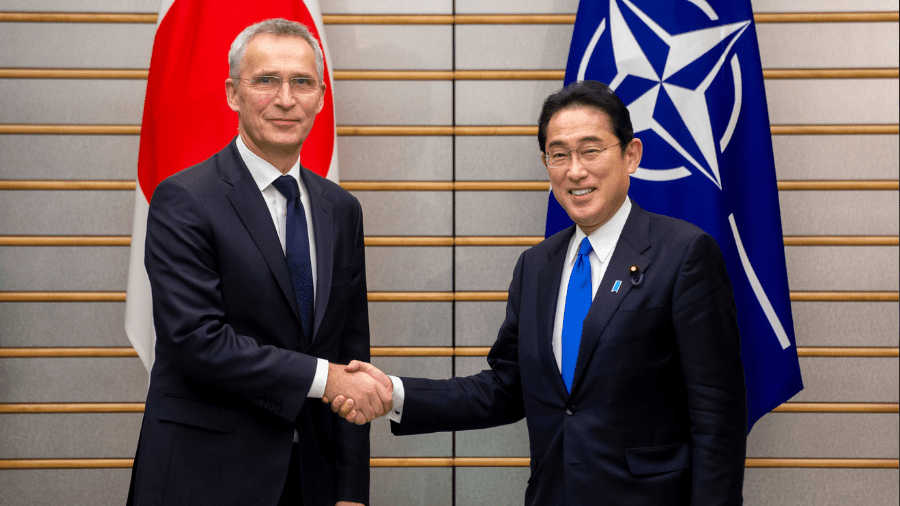

The highly coordinated response between Japan, the United States, the EU, Australia, New Zealand and NATO has demonstrated the utility of building more synergy into the Japan-NATO relationship. It’s this highly coordinated response that has helped the Ukraine push back against Russian aggression through a plethora of tools including economic sanctions, financial instruments and the threat of NATO being mobilized to defend its members.

All demonstrate that a multilayered and multinational front is necessary to protect, preserve and invest in the current rules-based order that has brought peace and stability to the region and the world in the post-WW 2 period. For Japan, cooperation with NATO can and should include intelligence sharing, maritime and other domain awareness activities, building resilience into defense systems including cyber and coordinating training for contingencies that may have global repercussions.

Japan needs to be sensitive to the views of Central and Eastern Europe who do not want NATO resources to be redirected to the Indo-Pacific region to mitigate and push back against Chinese assertive behavior in the South China Sea, across the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea.

This makes sense for Central and Eastern European countries. NATO resources should be placed in the geographic region that has the largest potential for disruption. That is the border with Russia.

Notwithstanding, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated that Japan needs to and must coordinate its activities, diplomacy, defense and build experience to contribute to a rules-based order not just in its geographic backyard but in all parts of the world to be a consistent, contributing and a good member of the international community.

At the same time, Japan needs to continue to articulate to NATO the serious concerns it has in the Indo-Pacific region. On the top of this list is a conflict or friction across the Taiwan Strait. For Japanese policymakers, this would disrupt sea lines of communication and technology supply chains and would be an existential threat to the Japan.

Conflict could spiral into a regional conflict including the United States, Australia, Japan, and others. Saliently, it would have economic repercussions for the region, the world’s most dynamic economic region. It would disrupt supply chains that provide valuable goods to NATO countries and it would likely make the supply chain disruptions associated with the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine look small and insignificant.

Here, Japan needs to find opportunities for NATO to cooperate within the region to ensure that sea lines of communication remain arbitrated by rules and is maximally inclusive. All states in this region depend on stable, peaceful sea lanes of communication for trade and economic engagement.

There are many things that Japan needs to do to be a more reliable partner for NATO. Japan needs to think about what are the appropriate assets that needs to contribute to NATO-Japan cooperation and where can they locate these resources within the region so that they can be accessed immediately. Lastly, the decision-making process or preparations within Japan for more seamless cooperation between NATO and Japan and other security partners is very important.

Key questions will include, what is the appropriate coordination mechanism between local and national governments? How to mobilize resources in a way that allows for Japan to work in a complementary fashion with NATO members on issues within the Indo-Pacific region and beyond?

Trial balloons to iron out these challenges could include search and rescue operations, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, maritime domain awareness activities and possibly participation in Quad activities and or the RIMPAC activities within the region. This joint participation by Japan and NATO partners in Quad training activities or RIMPAC activities, build shared norms, shared practices, trust and communication between like-minded countries to defend a rules-based order.

Simultaneously, it inculcates Japan into a community of like-minded countries understanding the importance of pushing back against dissatisfied authoritarian states that wish to revise regional orders such that neighbors of authoritarian states defer to authoritarian wishes rather than rule-of-law.

The Japan-NATO partnership will continue to evolve to be one that provides public goods and security guarantees to regions that are being challenged by military force. While this partnership evolves, it will be important to find ways to be inclusive as possible such that neighboring states see Japan-NATO partnership as one that provides public goods to the Indo-Pacific region.

Non-traditional security cooperation in the areas of pipe anti-piracy, illegal fishing sanctions invasions, such as the NEON exercises in the Sea of Japan provide platforms for building trust in a more inclusive fashion with states such as China that have selective but serious initiatives to transform the Indo-Pacific region.

Other areas of focus for Japan-NATO cooperation should be gray zone operations and lawfare operations that are conducted within the Indo-Pacific. Gray zone operations include using merchant vessels to move in and out of territorial waters of the Senkaku island or to swarm around geographic features in the South China Sea. Lawfare operations, such as the 2021 Chinese Coast Guard law enables the Chinese Coast Guard to use force in areas it considers Chinese territory but international law does not. Both contribute to a high chance of accidental conflict and highlight how Japan-NATO cooperation is imperative to protect the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific.

Both gray zone and law fare operations are likely the tools of transforming the Indo-Pacific region’s security architecture and rules-based management for sea lanes of communication to favor their strategic imperatives of China. Japan and NATO, through their cooperation, communication and collaboration should be clear that their activities need to find creative ways to mitigate these challenges while at the same time, present a positive, contributing form of cooperation to the region such that ASEAN and other stakeholders see Japan-NATO cooperation has a stabilizing partnership that does not compel them to choose between China and these emerging partnerships.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a Senior Fellow with the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.