This article originally appeared in Canadian Affairs.

By Sam Huyer and Richard Shimooka, November 10, 2025

A defining characteristic of the Canadian Armed Forces throughout its storied history has been the high quality of its personnel. They are resourceful, resilient, adaptive and value tradition.

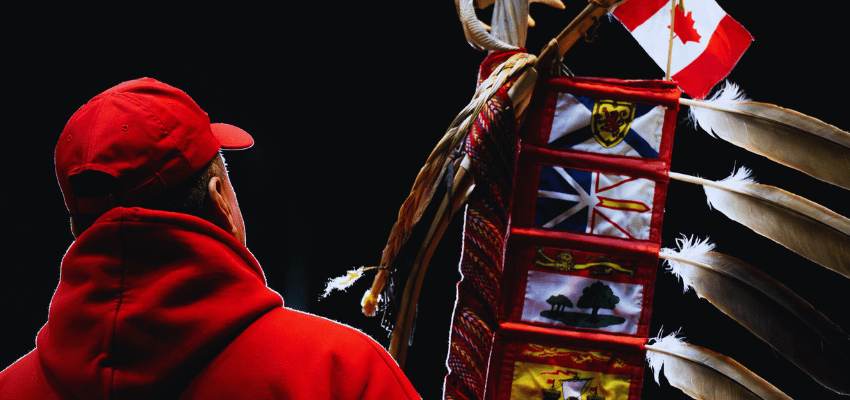

There’s another community that’s often described this way: Indigenous peoples.

So it should come as no surprise that these two groups share a long and storied history. Indigenous members consistently prove to be excellent soldiers, sailors and airmen, serving with the highest levels of distinction.

Inuit sniper John Shiwak’s skills as a hunter and trapper prepared him for distinguished service as a scout in the First World War. The Second World War saw First Nations servicemen such as Charles Tomkins of Alberta translate radio messages into Cree to thwart their interception by the enemy. On a nation-to-nation level, the Haudenosaunee entered treaties with the United States and Canada to fight against Axis powers. These are a few examples among many of the remarkable legacy of Indigenous veterans.

Were the alignment in qualities between the Canadian Armed Forces and Indigenous service members harnessed to its full potential, both groups would benefit.

Indigenous recruits offer the CAF many advantages over their non-Indigenous counterparts. They often bring practical life skills that the military prizes — such as marksmanship, and the ability to hunt and live off the land. Most Canadians have no such experience, much less aptitude and comfort, in these areas.

Similarly, the CAF offers a great value proposition to Indigenous youth.

The Forces present an alternative to a life on reserves and other communities — providing stable, lucrative employment across diverse occupations often not available to them at home. This can facilitate personal development, and build practical skills for youth to bring back to their communities.

There are also many intangible benefits that stem from service. Military service introduces its members to concepts such as discipline, duty and structure.

Leaving their communities may also help Indigenous youth see past stereotypes about the outside world — and even about themselves. Time away often provides Indigenous service members with new perspectives on their cultures, sometimes instilling them with a sense of greater pride and belonging when they return.

Yet, despite this tremendous potential, the CAF is squandering the opportunity.

Though a steady stream of Indigenous recruits enter the military’s ranks, they often face prejudice or even naked, systemic racism. Many soldiers feel they are held to a far higher standard than non-Indigenous members, often because they are under constant scrutiny from colleagues. It’s a testament to their indomitable perseverance that many still thrive in this difficult environment.

This must be remedied.

What sets this opportunity apart from other policies to promote diversity and inclusion within the CAF is the history and magnitude of the issue. First Nations have been an integral part of Canadian military history. This proposal is not a call to build new bridges to unfamiliar territory, but to refurbish an existing one on a well-trodden path.

To their credit, successive governments have made significant efforts to promote Indigenous recruitment. Programs such as Black Bear, Raven and Bold Eagle facilitate entry into basic training, while the Indigenous Leadership Opportunity Year (ILOY) exists for cadets at Royal Military College. At intake, Indigenous members make up about five per cent of recruits — which is roughly proportionate to the percentage of individuals who self-identify as Indigenous in the general population.

But more needs to be done, particularly to retain Indigenous members already in the service.

Indigenous members have the lowest retention rate of every other identity group, save for women from a visible minority.

The CAF should move from tolerating Indigenous practices to respecting and even celebrating them when appropriate.

While unit cohesion and discipline are absolutely vital for a military’s successful operation, acceptance of items such as some Indigenous hairstyles and traditional observances would open up a pathway to harness the potential of more Indigenous youth.

For example, the CAF should expand the number of military chaplains who can lead the observance of Indigenous ceremonies.

Few would doubt that Indigenous soldiers are committed to their comrades in arms, their units and the Crown. The CAF must reciprocate this dedication.

Sam Huyer is a Canadian Studies & Indigenous Studies graduate student at Trent University.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at the McDonald Laurier Institute.