Unlike the Idle No More Protests, these protests around Coastal GasLink threaten to broadly subsume Indigenous rights in a campaign against Canadian oil and gas, contrary to the expressed preferences of many Indigenous governments and community members, writes Ken Coates.

By Ken Coates, February 14, 2020

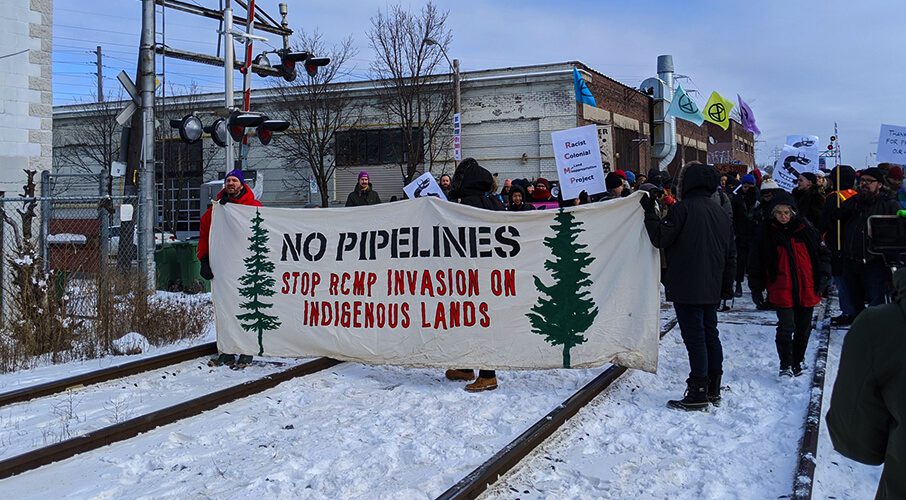

Waves of blockades and protests against the Coastal GasLink pipeline have knotted up the country. Trains have been stopped. Access to the British Columbia Legislature has been impeded. Construction work is being affected along the pipeline corridor. Intersections have been blocked in major cities.

And as Indigenous people figure prominently in all the events, with signs supporting the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who are central to the conflict, Canadians are struggling to make sense of it all.

That is understandable. It seems like a classic conflict between Indigenous peoples and resource developers, or at least, Canadians might understandably make connections to the Idle No More movement that was launched seven years ago. But that’s not what this is. The differences are much greater than the similarities.

The Wet’suwet’en situation has proven to be complex, reflecting legal and political uncertainty about the nature of decision-making in the region. While a group of hereditary chiefs oppose the pipeline project, the chief and council of Witset First Nation – the largest band, elected through the Indian Act, within Wet’suwet’en Nation – support the project, as do what appears to be a large majority of First Nations’ members along the pipeline’s route.

Hereditary chiefs played a vital role in the campaign for the recognition of Indigenous land rights, and they have reason to expect active involvement in local political affairs. Other northern British Columbia First Nations incorporate hereditary chiefs into their formal decision-making processes. That has not been done, as yet, among the Wet’suwet’en.

But this situation over Indigenous rights has been complicated by some anti-pipeline activists looking to advance their cause.

Idle No More, in contrast, was a loosely managed movement that called on Indigenous peoples across Canada to champion local issues, to express their dissatisfaction with Canadian policy, and to celebrate Indigenous resilience. Hundreds of pop-up events happened across Canada, marked by their dancing, drumming and singing, their optimism, and the determination to ensure that Indigenous voices were heard by government, politicians and the public at large.

The Idle No More events were also overwhelmingly peaceful and legal. It was a matter of pride for supporters that they posed minimal disruption: There were some short-term road and rail blockades, but the vast majority of the events formed and dissipated quickly. They represented the largest, most sustained and most impressive declaration of Indigenous confidence, revitalization and determination in Canadian history, as Indigenous people – mostly young, and with many women involved – asserted their right to speak. Supporters around the world gathered, sang and danced in solidarity. As a movement, Idle No More had no specific policy objectives and no clearly defined political mandate, and therein lay its success and authority.

The current protests, however, focus on civil disobedience, deliberately working to inconvenience non-Indigenous peoples. And as the disruptions and costs mount, they risk giving Canadians the wrong impression about Indigenous peoples’ distinctive relationships with the natural-resource economy and pipelines. In the age of national commitment to reconciliation, the resource sector has emerged as the front line of national renewal and transformation. Indigenous communities have capitalized on a long series of court decisions in their favour to forge a new role in the energy industry. Indigenous employment and business activity have expanded dramatically.

The impression given by these protests – that Indigenous peoples are uniformly opposed to the pipeline or energy development – is simply wrong. There are certainly committed and energetic Indigenous backers of the protests, but they do not represent all Indigenous peoples and communities.

Idle No More sparked a surge in Indigenous assertiveness, and it ushered in an era of Indigenous activism. There are aspects of Idle No More that made some non-Indigenous peoples uneasy; pressure on governments has certainly increased, as has the insistence that attempts at reconciliation be real and substantial. But since that time, Canadians have become much more comfortable with the idea of Indigenous peoples playing a strong and expanding role within the country.

These protests around Coastal GasLink, on the other hand, threaten to broadly subsume Indigenous rights in a campaign against Canadian oil and gas, contrary to the expressed preferences of many Indigenous governments and community members.

The Coastal GasLink activities run the risk of alienating public support for Indigenous rights and aspirations. What a bitter and destructive irony it would be if the willingness of the environmental movement to engage selectively in the politics of Indigenous rights ends up weakening the people they claim to be supporting.

Ken Coates is a Munk senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.