This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Shawn Whatley, December 1, 2025

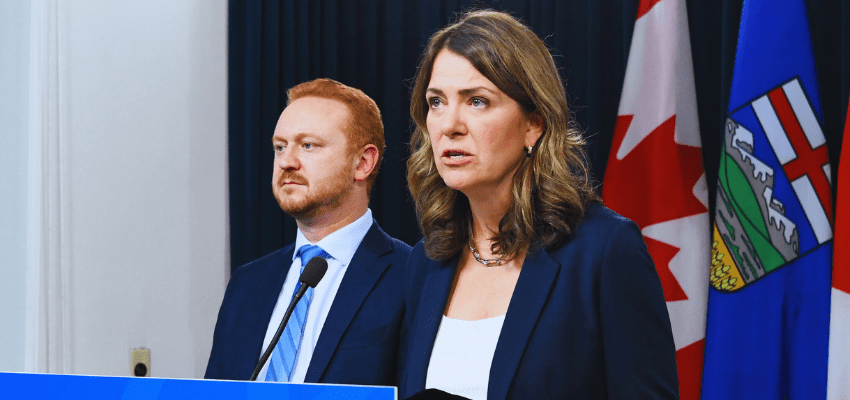

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith’s government has introduced new legislation that would allow patients to pay for medical care themselves, directly or with personal insurance. This may sound like private care, but it’s not what people might assume — or hope for.

Under Bill 11, tabled Nov. 24, the province’s medical care will remain heavily regulated and centrally controlled. Patients will simply be able to pay for it themselves, and doctors will be able charge outside the public queue. The bill also permits doctors and nurses, in limited cases, to accept private payment at specified hours and locations, overseen and monitored by government.

The plan sounds a bit like government announcing a new way for citizens to send mail — at higher cost, in a post office across the street. The state will continue to regulate and monitor everything to do with letters, including volume and handling. It will still manage staffing details like breaks, hours and the ratio of staff time spent in public and “private” post offices.

On one hand, Smith’s announcement might be the biggest step we can expect in Canada, even from Alberta. That warrants kudos. But we should withhold applause until we see real change in wait times and service for actual patients.

Advocacy groups like Friends of Medicare oppose the plan, calling it “American-style two-tiered health care.”

The Canadian Medical Association released a statement arguing “evidence from around the world is clear: where a parallel private health system operates, both health outcomes and access to care are worse.” The statement carries the same logic as saying, “in regions where citizens own more umbrellas, rainfall and thunderstorms are worse.” The umbrellas did not cause the rain.

Despite these predictable reactions, the proposal’s potential impact should be kept in perspective. In fact, medicare advocates have, in the past, dismissed the idea that private insurance threatens Canada’s health-care status quo.

Following the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2005 Chaoulli decision — in which the court ruled a prohibition on purchasing private health insurance for essential medical services violated Quebec’s human rights charter — medicare supporters feared the worst. Colleen Flood, Queen’s University’s law school dean and outspoken medicare defender, was among the experts called upon to weigh in.

Flood reassured her friends, predicting Chaoulli wouldn’t make a big difference. She turned out to be right.

“Many countries use a range of other indirect methods apart from expressly prohibiting private health insurance to protect the public system,” wrote Flood. She said Canada was the same.

However, she predicted Charter challenges to other laws that impede privatization, which she said were much more important to “suppressing a developing second tier.”

On this point, her prediction never came to pass. No one has bothered to challenge them.

For example, Ontario’s Protecting the Future of Medicare Act 2004 bans physicians entirely from offering medically necessary care (i.e., working) outside the public system, never mind just banning dual practice. As for the “other indirect methods,” those obstacles remain firmly intact: regulations, policies and procedures are legion. Under Alberta’s proposal, they will persist.

In fairness, Smith did tackle health care, the third rail of Canadian politics. She is expanding services. Patients won’t have to wait as long. Doctors and nurses won’t be marooned in inefficient, unionized, publicly funded hospital behemoths.

But if we hope for a meaningful drop in patient wait times and the cost of care, we need to reframe the question around patient needs, not government allowances.

Our whole system pivots on governments rationing care, or limiting available care based on government spending. Patients needs currently far surpass any government’s ability to dole out the required rationed hours to have patients’ needs met.

In his new book, Dr. Brian Day describes how orthopedic surgeons used to have approximately 17-22 hours per week of operating time allotted to them in the 1980s and ’90s. Today, they have five. Canada has massive, untapped, rationed care capacity.

Remember, rationing harms the poor, elderly, immobile and least socially influential patients. Wealthy, well-connected patients need never complain about access. Slightly increasing the availability of services on the government’s terms, as Smith proposes, is rationing by another name.

Central planning never increases available goods and services. That’s why politicians should blanch at the notion of government “allowing” dual practice. Dictating terms of practice means that when doctors and nurses cannot meet them — due to family responsibilities or many other factors — they have no choice but to leave practice altogether. That’s happening already, with patients bearing the impact.

If governments want true change, we must consider a larger set of policies: service type, price, volume, location, oversight, who delivers services, to whom and who makes these decisions. If governments continue to insist on controlling — either directly or through subsidiaries — all the details about medical care, then medicare will continue to function much like a passport office.

Given all that’s been thrown at Smith from the left for attempting a small change, we might hesitate to tackle from the right. But we should only applaud changes that make a difference. Let’s hope this proposal makes a positive difference for Alberta patients.

Shawn Whatley is a physician, past president of the Ontario Medical Association, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and author of “When Politics Comes Before Patients: Why and How Canadian Medicare is Failing.”