This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, September 10, 2025

In our hyperconnected age of instant news and viral images, too many international-relations “analysts” and “commentators” resemble phone-clutching adolescents, lurching from one snapshot moment to another, proclaiming epochal shifts based on photo ops and fleeting diplomatic encounters while ignoring the deeper structural currents that shape global power dynamics.

Consider the whiplash-inducing coverage of recent events. When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy faced what some described as a humiliation at the White House in February, pundits declared it proof of America’s abandonment of its allies. Yet weeks later, his warm reception at the Vatican spawned equally breathless commentary about Europe’s ascendant moral leadership.

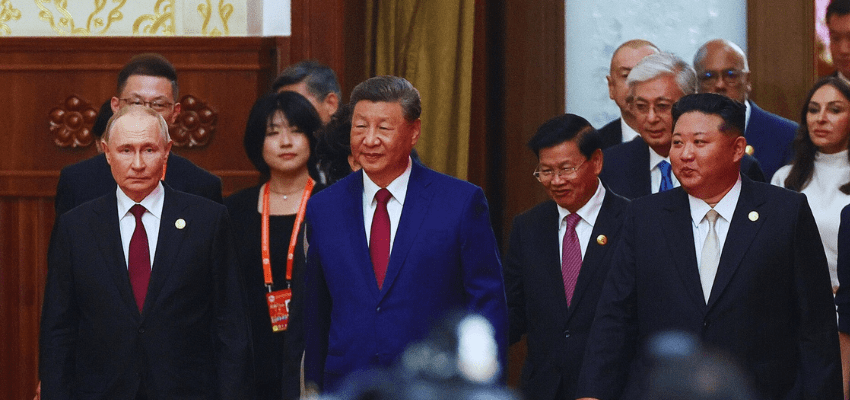

Similarly, when U.S. President Donald Trump successfully pushed NATO members to commit to spending 5% of gross domestic product on defense, some heralded American strength renewed, while others saw desperate overreach. Then came the Sept. 3 military parade in Beijing, where the image of Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un flanking Chinese leader Xi Jinping prompted declarations that U.S. dominance had definitively ended.

Such snapshot analysis reveals more about our collective analytical immaturity than about actual shifts in international order. The inconvenient truth is that none of these theatrical moments fundamentally altered the distribution of global power, the strength of institutions or the trajectory of long-term trends in demographics, technology, energy infrastructure or capital flows.

This teenage approach to watching the world has plagued us for decades. To illustrate, witness the regular productions of “the end of American dominance,” a show that has run longer than any Broadway musical. After the post-World War II stalemate in Korea, commentators declared U.S. military supremacy finished. Vietnam supposedly marked the empire’s twilight. The Soviet Union’s Sputnik moment in 1957 meant technological eclipse. The Iran hostage crisis proved American impotence. After 9/11, asymmetric warfare had supposedly rendered conventional power obsolete. The 2008 financial crisis was capitalism’s death knell. Trump’s first election in 2016 and his return in 2024 each spawned cottage industries predicting American democratic collapse.

Yet here we are, with the U.S. still commanding the world’s largest economy, most powerful military and most extensive alliance network. The dollar remains the global reserve currency, U.S. universities dominate global rankings and Silicon Valley continues to drive technological innovation.

The mirror image of this analytical adolescence appears in predictions about China. How many times have we heard that China will inevitably collapse or democratize? The Great Leap Forward would destroy Communist Party legitimacy. The Cultural Revolution would tear the country apart. The Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 was supposedly the beginning of the end. The COVID-19 pandemic would finally expose the regime’s fundamental weaknesses. Yet China’s economy has grown 40-fold since Tiananmen, lifting hundreds of millions from poverty while maintaining single-party rule.

These perpetual mispredictions stem from our addiction to dramatic moments over structural analysis. A photo of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Putin holding hands or Trump glowering at the Group of Seven leaders in Quebec captures attention and drives engagement but tells us virtually nothing about the underlying distribution of capabilities, the health of institutions or the momentum of long-term trends. Behind every staged photo-op lie countless untold stories about budget allocations, demographic transitions, educational investments, gender equality progress (or regression), infrastructure development, legal reforms and technological innovation. These are the real drivers of international change.

For those serious about understanding U.S.-China strategic competition and its implications for the world, Japan and other middle powers, we must turn to more sophisticated analytical tools. Comprehensive power indices like the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index or similar global power measurements offer multidimensional assessments that capture economic resources, military capability, diplomatic influence and cultural reach over time. These tools reveal patterns invisible to snapshot analysis.

What do these deeper examinations tell us? First, China’s power trajectory appears to be peaking, if it hasn’t peaked already. The country faces a devastating demographic transition with a rapidly aging population and shrinking workforce. Environmental degradation threatens economic sustainability. Debt levels at local governments imperil fiscal stability. Xi’s increasing authoritarianism has stifled innovation and prompted capital flight. China will remain a major economic force, but an increasingly fragile one, distracted by internal challenges and peripheral priorities including unifying with Taiwan, dominating the South and East China Seas, securing the Himalayan plateau and maintaining stable energy supplies from an increasingly desperate Russia.

The U.S., meanwhile, faces what analyst David Baverez identifies as twin structural challenges of servicing its massive debt while sustaining global military commitments. Yet American power shows remarkable resilience, rooted in dynamic demographics (thanks to immigration), technological innovation, energy independence and unmatched alliance networks. The trajectory is one of fluctuation rather than linear decline.

Europe, for its part, exhibits clear stagnation. It is caught between demographic decline, energy vulnerability and an inability to forge common strategic purposes. These are not trends that photo-ops can reverse.

For Japan and other middle powers, these structural realities are, like glaciers, gradually accumulating. They demand sophisticated strategies beyond simplistic choices between Washington and Beijing. The path forward isn’t diversifying away from the U.S., which remains the indispensable power for regional security and economic openness. Rather, it requires building a genuinely multipolar Indo-Pacific that dilutes Chinese centrality through overlapping networks of partnership.

This means investing in long-term relationships with India and ASEAN based on what I call “soft multialignment.” It is a flexible, problem-solving oriented partnership that addresses specific functional needs without requiring exclusive loyalty. Japan and India have pioneered this approach through decades-long collaboration involving real investment, security cooperation at bilateral and minilateral levels and deep people-to-people exchanges. These patient, structural initiatives — not summit theatrics — constitute the real news in international order transformation.

While talking heads parse the body language of authoritarian leaders, the real work of shaping international order proceeds through unglamorous channels such as infrastructure-finance initiatives, educational exchanges, technology-standards agreements, supply-chain diversification and military interoperability protocols.

The most important developments rarely photograph well. The gradual shift of global economic gravity toward the Indo-Pacific, the painstaking construction of new regional institutions, the slow-motion demographic transitions reshaping national capabilities — these processes unfold over decades, not news cycles.

When every summit becomes existential and every diplomatic slight portends systemic change, we lose the ability to distinguish genuine structural shifts from theatrical noise. Worse, this analytical immaturity creates self-fulfilling prophecies, as leaders feel compelled to respond to perceived slights and manufactured crises rather than focusing on long-term strategic imperatives.

The solution begins with analytical maturity. This includes recognizing that international politics, like geology, involves both dramatic earthquakes and imperceptible tectonic shifts, but the latter ultimately reshapes the landscape. We need commentators who understand budgets as well as body language, who track institutional evolution alongside summit declarations and who recognize that a nation’s power rests more on its education system than its military parades.

For middle powers navigating U.S.-China competition, this deeper analysis reveals opportunities invisible to snapshot observers. The real game isn’t choosing sides in a bilateral confrontation but building resilient networks that preserve agency and create options. It’s about turning the bipolar moment into a multipolar future through patient institutional entrepreneurship.

The images of authoritarian leaders clasping hands may generate clicks, but the patient construction of new partnerships, the gradual diversification of supply chains and the quiet strengthening of regional institutions will determine whether the Indo-Pacific’s future is defined by hegemony or pluralism. That’s not teenage analysis, it’s the mature understanding our turbulent times demand.

Stephen R. Nagy is a professor of politics and international studies at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs, and a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.