This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, August 21, 2025

After three years of financial losses, it appears the Bank of Canada has returned to profitability.

This marks a significant turnaround. The Bank began experiencing losses for the first time in its history during the summer of 2022. At the time, few expected the scale of losses that would ultimately unfold. In November 2022, the Bank itself projected total losses between $5 and $6 billion over several years. My University of Calgary colleague Professor Sonja Chen and I conducted a separate analysis for the C.D. Howe Institute, estimating losses ranging from $3.6 billion to $8.8 billion, with a mid-range estimate of $5.7 billion.

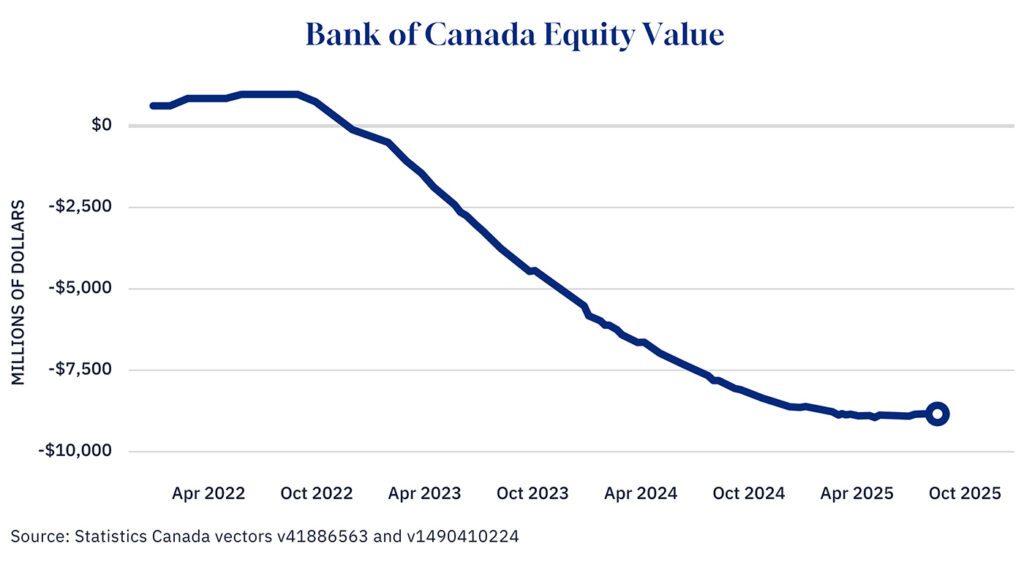

While the exact total remains unknown until the Bank’s financial statements are released later this year, recent data allows us to get close. The Bank’s equity position has shifted dramatically—from a peak of nearly $1 billion in the summer of 2022 to a negative value of nearly $9 billion by the end of June 2025, when it bottomed out. This implies cumulative losses of approximately $9.9 billion, which exceeds even the high-end estimate of our previous work.

Importantly, the Bank of Canada was not alone in facing losses. Central banks in many countries—including the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, the Eurozone countries, Switzerland, and more—experienced similar challenges during this period. But understanding the causes of this experience, and its implications for the Bank and the broader federal government, is important nonetheless, despite this being a common experience.

Why the Bank of Canada lost money

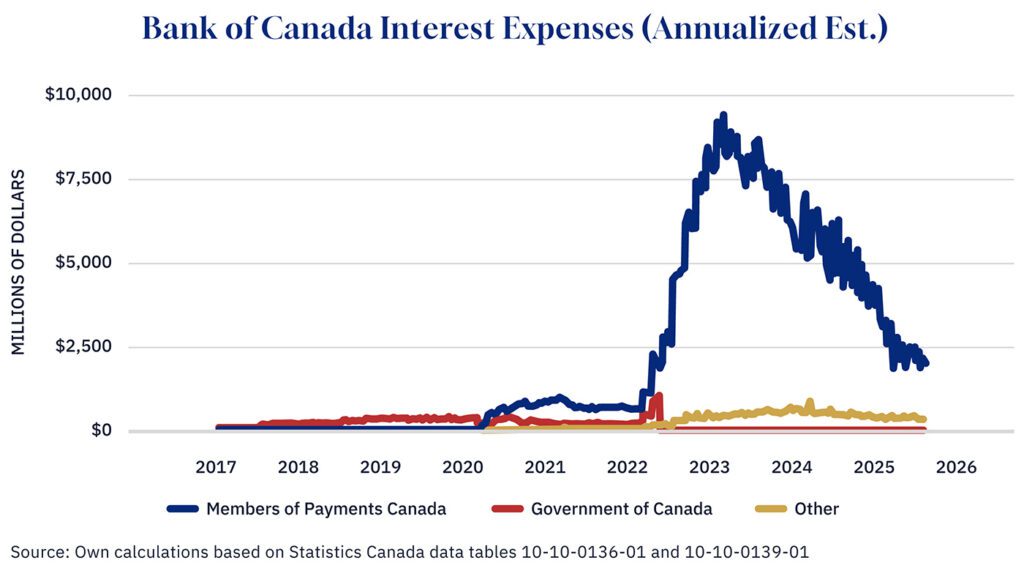

Unlike commercial banks, the Bank of Canada’s operations are relatively straightforward. Its income is largely derived from interest earned on government bonds. Its expenses include typical operational costs—wages, salaries, equipment, computing, and the production of banknotes. In addition, the Bank pays interest on deposits that commercial banks, the federal government, and a few other entities make at the central bank.

Normally, these deposits are modest. Before the pandemic, deposits from commercial banks rarely exceeded a few hundred million dollars, and federal government deposits hovered around $20 billion. As a result, the interest paid on these deposits was relatively small compared to the Bank’s overall income. For instance, the Bank reported a profit of roughly $2.8 billion in 2021, with the government receiving the majority as a dividend.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Bank’s monetary policy response dramatically altered this picture. To stabilize financial markets and support the economy, the Bank undertook quantitative easing—purchasing large volumes of government bonds to lower interest rates. This strategy was effective, but it also swelled the Bank’s holdings to nearly $450 billion at their peak, up from about $80 billion pre-pandemic. Because these bonds were mostly purchased from financial institutions, the proceeds were largely deposited back at the Bank of Canada, causing commercial bank deposits to surge.

That’s not itself a problem, but it exposed the Bank to risks. As inflation rose and interest rates increased in response, the Bank’s interest expenses also ballooned. After all, it had to pay a higher interest rate on the now significant deposits that commercial banks now had at the Bank of Canada. This resulted in substantial losses.

The road back to balance

Since then, the Bank has been unwinding its pandemic-era bond holdings. It has allowed maturing bonds to roll off its balance sheet, cutting its federal government bond holdings by more than half. Commercial bank deposits have also dropped—from nearly $400 billion in early 2021 to about $80 billion today. Interest rates have declined as well, reducing the Bank’s expenses and bringing its income and expenditures back into closer alignment.

These developments have important implications for the federal government. As a wholly owned Crown corporation, the Bank’s losses are reflected in the Government of Canada’s financial statements, contributing to a larger federal deficit than would otherwise have occurred. And in the coming years, the Bank will retain its earnings to rebuild its equity position before resuming dividend payments to the government. It’s hard to say how long this will take, but based on my previous analysis, it may last until the end of the decade.

Public and political reactions

To be clear, the Bank of Canada is not a typical corporation. Its losses don’t imply that there’s any real insolvency risk here. It prints money, after all. But losses still mattered for at least two important reasons.

First, rising interest expenses of the Bank of Canada should be thought of no differently than debt service costs of the overall federal government. Losses, in effect, increased the government’s deficit, and the return to profitability reduces this drag on the federal budget. Fewer commercial bank deposits at the Bank of Canada effectively mean a reduction in short-term borrowing by the federal government, which in turn lowers interest payments.

Second, the potential for broad public misunderstanding of the central bank’s financial losses was significant. Although, surprisingly, at least to me, this episode has generated far less political and public backlash than I anticipated. When Professor Chen and I released our paper through the C.D. Howe Institute, we flagged the potential for credibility and communication issues. We warned that critics could seize on these financial losses to undermine public trust in the Bank. Yet, it turned out, very few have written about the Bank’s losses and fewer still have misrepresented them.

The dominant public concern has instead been inflation and the perceived mismanagement of monetary policy. This is a legitimate and ongoing debate. For instance, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has been sharply critical of the Bank, at one point calling it “financially illiterate.” But even that criticism was more focused on monetary policy choices than on the Bank’s profit-and-loss position.

Credibility and communication risks remain, though.

New era, new risks

The Bank now finds itself operating in a new era of monetary policy. We may not return to the pre-pandemic model of minimizing commercial bank deposits at the Bank of Canada. While current commercial bank holdings of about $80 billion seem modest compared to the pandemic peak, they are still nearly 300 times larger than typical pre-pandemic levels.

This new normal carries greater exposure to interest rate risk. The probability of future financial losses has increased, and that’s where the challenge lies. While broad public attention and concern during this experience were muted, they may not be in the future.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum