This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Heather Exner-Pirot, November 30, 2023

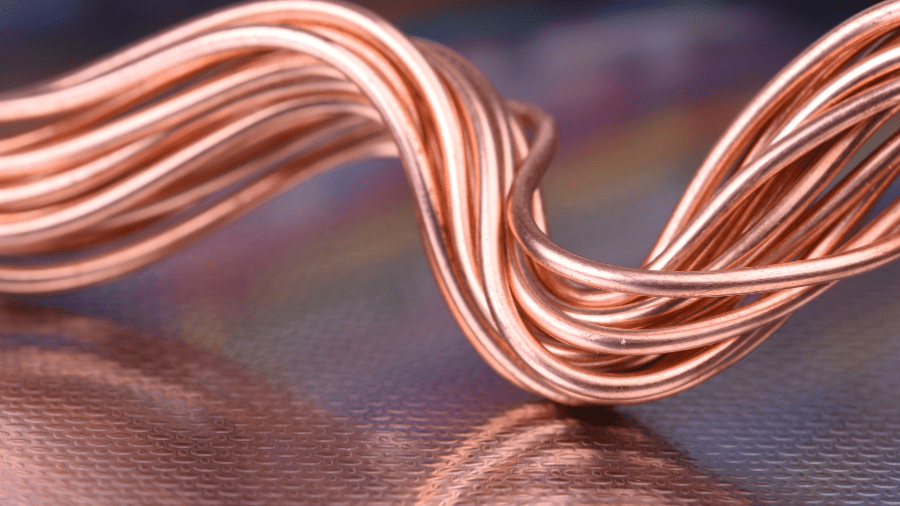

Copper is the metal of electrification. It’s essential for power transmission, batteries, renewables and more. Most net-zero scenarios require a doubling of production for the red metal, an unlikely task made impossible without greater dependence on Chinese supplies.

Events in Panama this week with Canadian miner First Quantum Minerals Ltd. show how a world opposed to more copper extraction will fail to displace fossil fuels.

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the role of metals such as copper, nickel, lithium and rare earths in the energy transition, earning them the moniker of “critical minerals.”

The Russian invasion of Ukraine highlighted the folly of relying on potential adversaries for your energy security. It led to the realization among the West’s political class that the production of most energy-transition metals is concentrated in a handful of countries, many of them politically unstable, before being refined in China. The supply chain for clean electricity is a tightrope.

The vulnerability of net-zero goals to an adequate supply of critical minerals was further exposed this week when the Panama Supreme Court declared First Quantum’s contract to operate its Cobre Panama copper mine unconstitutional, prompting the Panamanian President to shut it down.

The mine had been producing around 1.5 per cent of the world’s copper. But despite its importance to the Panamanian economy, accounting for about 5 per cent of GDP, environmentalists, students and other groups protested against its environmental impact. In recent weeks, there had been road and sea blockades, leading to supply shortages and social unrest in that country.

Combined with mining protests and disruptions in copper heavyweights Peru and Chile this year, a long-anticipated structural deficit in global copper supplies could be around the corner. S&P Global, a commodities consultancy, anticipates that a chronic shortfall in copper supply could reach 10 million tonnes by 2035, or about 20 per cent of what’s needed to achieve net zero.

It’s not only countries in the Global South where copper production is being challenged. Consider that in 2023, federal agencies in the United States rejected projects for not one, but two, world-class deposits: the Pebble Mine in southwest Alaska, which would have negatively affected salmon habitat, and the Twin Metals mine in Minnesota, which would have had an impact on waterways in the popular Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Meanwhile, in Canada, despite recent critical-mineral strategies and supports, copper production is in a decades-long descent. According to the Mining Association of Canada, refined copper production declined 43 per cent between 2005 and 2018, the most recent year available. And raw production is not doing much better, having fallen 8 per cent since 2019. Canada is no longer a top 10 producer of copper.

How can we account for the mismatch between the need for copper, and our unwillingness to produce it?

It is not that there is no copper available: There are healthy levels of identified resources of copper, 2,100 million tonnes worth, almost two-thirds of which are found in South and North America. It is that we, as a society, be it in Canada or Panama, still do not understand that resource extraction is not an option, it is a requirement.

The reckoning that has yet to come is that we will not achieve our climate goals without massive growth in copper and other mineral extraction. Yet the same environmental groups and governments that advocate for ambitious climate policies have done nothing to make mining easier, faster or more attractive to investors. Quite the opposite.

Regulatory and permitting challenges are well-known problems, but they don’t stop there. Even if a mine gets approved, cost overruns are a real possibility, as Teck Resources Ltd.’s flagship QB2 copper project in Chile shows. Teck announced last month that its costs had spiralled from an estimated US$4.7-billion in 2019 to US$8.7-billion, an 85-per-cent jump.

And the Cobre Panama saga shows that even if you get a world-class project approved, built and into production, it might still be shut down.

All these risks have weighed heavily on global mining investment, which has yet to reach its 2013 peak. We are not building up for an energy transition; we are living off investments made a decade ago.

The fate of the energy transition does not rest with battery factories, EV mandates and investment tax incentives. It rests with mining enough copper and other critical minerals to move from a fossil-based energy system to a minerals-based one.

Unless we can accept resource extraction as an essential element of this plan, all we will be left with is a more vulnerable energy system.

Heather Exner-Pirot is director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.