This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Fen Osler Hampson and Tim Sargent, February 17, 2026

Prime Minister Mark Carney won many plaudits for his recent speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in which he warned that the rules-based economic order is over, and that “middle powers” such as Canada must work together against great-power coercion. The speech continued making waves at last week’s Munich Security Conference.

But talk is cheap and applause is free. And the blowback from U.S. President Donald Trump has been harsh and long-lingering. Also last week, Mr. Trump threatened to block a new Windsor-Detroit bridge and demanded to be “fully compensated for everything we have given” to Canada – despite the fact that Canada paid for the entire project.

Without a concrete proposal for rallying the middle powers, the Prime Minister might have been better to confine himself to the usual platitudes of high-level international meetings, and to avoid antagonizing the world’s most powerful country. He needs to follow up, and quickly. The “rupture” to the world order, as Mr. Carney calls it, hits a trading nation such as Canada particularly hard. Without action to back up Mr. Carney’s words, our lives will get harder and meaner.

Canada, along with other advanced democracies such as Britain, Norway, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and the countries of the European Union, should look beyond traditional diplomacy. They should seek to establish a 21st-century version of the Hanseatic League: an informal alliance of hundreds of cities and merchant guilds along the North and Baltic coasts in medieval times. This group, which grew out of German towns, successfully formed a commercial and defensive network to stave off the predations of neighbouring states such as Denmark, England and Russia.

The power of such an alliance today would come not from military strength, but from the sophisticated market-power leverage these countries exercise over global finance and trade.

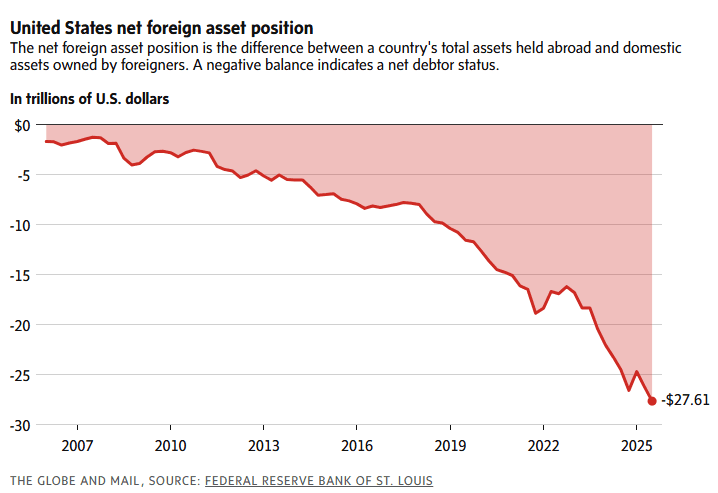

A key lesson from the recent skirmish over President Trump’s ambition to acquire Greenland is not just the pushback he got from some leaders at Davos; it is also the market reaction to the possibility that European creditors might start to dump U.S. bonds if the conflict escalated into a full-blown trade war.

The true Achilles’ heel of the U.S. is its exposure to its creditors and foreign investors, with its net foreign debt – public and private – now standing at more than $27-trillion, compared to only $8-trillion a decade ago. When the threat of instability begins to manifest itself as a spike in bond yields (which move inversely with prices) or a sudden decline in share prices, the economic costs of predatory behaviour are immediately apparent.

Between the sovereign wealth funds of Norway and Australia, the massive pension portfolios of Canada, Britain and many EU members, and the government bond holdings of Japan, these countries together control a critical mass of global liquidity. By themselves, each is not enough to make the United States blink. But if they were to coordinate their risk assessments, this group could act as a kind of global financial security council.

If a great power engaged in behaviour that undermines international stability through economic coercion or a violation of state sovereignty, the world’s middle powers could signal their plans to recalibrate their vast financial holdings. A coordinated shift in the bond holdings or a staged reassessment of a great power’s sovereign risk premium would trigger an immediate market reaction, forcing a predatory actor to reassess its geopolitical ambitions.

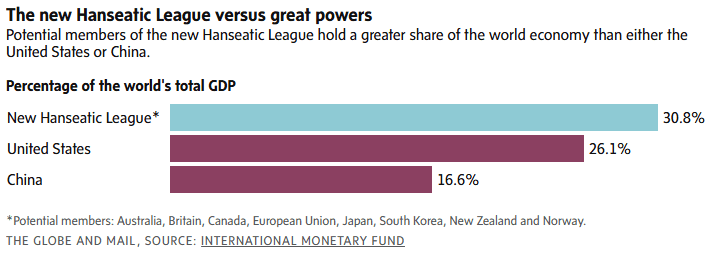

These countries are also large economies in their own right. Our new Hanseatic League of advanced democracies accounts for 30 per cent of world’s gross domestic product (measured in U.S. dollars). This is very relevant for dealing with China, the other great power that is not afraid to menace smaller countries.

Unlike the U.S., China is a net creditor country, and so is not vulnerable to a coordinated retreat from its asset markets. However, this net asset position has been built up by chronic trade surpluses, generated by an economy that produces way more than it can consume. As a result, China would be quite vulnerable to a coordinated action to restrict its exports, which would shutter factories and lead to the kind of social unrest that the communist regime seeks to avoid at all costs.

The key organizing principle of the league should be an economic equivalent of NATO’s Article 5: an attack against one is an attack against all. This collective defence mechanism would neutralize the “divide-and-conquer” strategy employed by great powers, transforming a bilateral dispute into a confrontation with a powerful and unified coalition.

As with its military counterpart, the new league should have a permanent secretariat that could war-game potential threats and responses, while maintaining continuous informal communications between central bankers, fund managers, finance ministers and political leaders.

How can Canada make this happen?

The first step would be for the Prime Minister, fresh from his Davos success, to talk to other leaders to rally them to this cause. This should not be too difficult, given their reactions to Mr. Carney’s speech and how their moment of unity carried the day at the forum. Moreover, there is an existing platform off which to build: Canada has already set up the Ottawa Group, a collection of middle powers including the EU that has sought to preserve a rules-based trading system.

Mr. Carney should then bring the leaders together for an inaugural meeting that would make clear the league’s willingness to use its collective economic and financial muscle. Canada could offer to host the secretariat in Ottawa and provide the necessary resources. This kind of convening role is well suited to Canada’s diplomatic strengths: We were heavily involved in the creation of original postwar international institutions, such as the UN or NATO itself.

Of course, there are risks. Neither the U.S. nor China is likely to welcome such an alliance, and Canada, with its dependence on the American economy, may be particularly vulnerable. Economic and financial coercive measures also carry a cost for the states imposing them. A coordinated sell-off of U.S. bonds, for example, pushes down their value and hurts the countries selling them, too.

However, standing up for oneself always carries a price, no matter the method, and that price is small compared to the cost of rolling over. We are less dependent on the United States than Mr. Trump likes to think: The reality is that the U.S. trades with Canada not because it likes us, but because it needs our energy and raw materials.

Both President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping have made it abundantly clear that they respect only strength. “Going along to get along” will simply mean an endless series of concessions. The path forward for middle powers lies in recognizing that their strength is primarily financial and economic over military.

A fit-for-purpose Hanseatic League for the 21st century would send a strong message that power in the international system does not just reside in Washington or Beijing, but also with the world’s Lilliputians.

Fen Osler Hampson is Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University.

Tim Sargent is director of domestic policy at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a former deputy minister of trade.