This article originally appeared in the Hill Times.

By Martin Green, January 26, 2026

A cacophony of national security trends and threats are rightly a central part of Canada’s current public discourse.

There is a refreshing consensus on the imperative of Canada’s defence and national security missions, and therein having the strong “intelligence” collection and analysis capabilities that our leaders—and Canadians—must have to be strategically competitive, secure, and resilient.

As a military brat, and during my time as a senior national security and intelligence official, I often wondered why Canada didn’t have a dedicated human foreign-spy agency. Putting aside the fanciful notions of a Canadian 007 or Mission Impossible, the short answer is that we are a part of the 21st-century “great game.” But we need to better use our existing capabilities and authorities domestically and internationally.

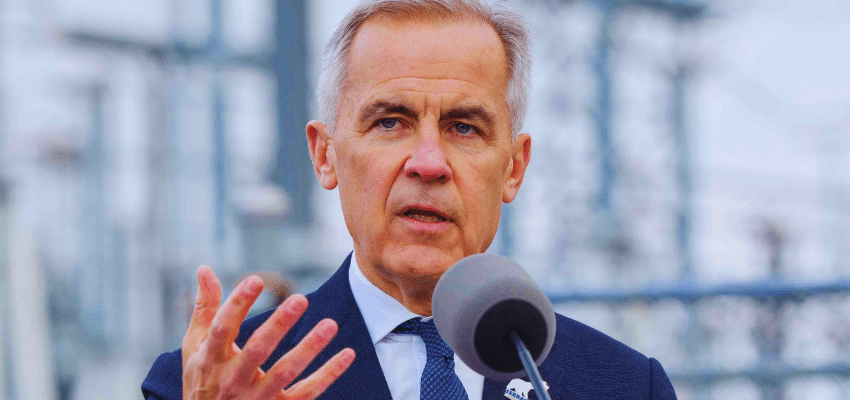

As Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government articulates a new and welcomed vision for defence and national security, a decades-old discussion of this country having its own Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or Secret Service (MI6) type spy organization has been percolating.

The renewed impetus for this appears to be that the United States under President Donald Trump is no longer a reliable partner—partly true. And, that Canada needs to focus on and bolster its national security apparatus in the face of growing nefarious trends and threats—true. I don’t think, however, that these are compelling reasons for Canada to embark on such a disruptive, time consuming, and costly machinery change. Urgency dictates that we prioritize, consolidate, and build on what we have.

Trump’s first presidency raised a lot of eyebrows in the world’s intelligence communities. His contempt for his own intelligence community and attempts to politicize them were at best counter-intuitive and unsettling. The U.S. spy community—who are, by and large, dedicated and professional—was stirred (not shaken) by this development, and they remained relatively unscathed with trusted foreign partnerships intact.

Trump 2.0, fuelled by a four-year break and a belligerent National Security Strategy, has politicized and weaponized almost every aspect of the American government. Leadership across the U.S. intelligence community has been decapitated and replaced with an almost tragicomical array of lap dogs.

This is unquestionably disturbing for the G7, Five Eyes, NATO members, and other partners. It is particularly so for Canada, as we have been a net beneficiary of our unique and historic integration with the behemoth American national security, intelligence, and military apparatus. As troubled, divisive, and deplorable as the Trump administration appears to most Canadians (and, I believe, the majority of Americans) it is inconceivable that either country would or should attempt to fully decouple or bifurcate from these partnerships. There is simply too much at stake and in our common interests.

While Canada should always be diversifying economically and bolstering our sovereign national security capabilities, it is unrealistic and foolhardy to think the two countries can fully disengage. While our relationship with the U.S. has permanently changed and remains fraught, out of pragmatic necessity a “quantum of solace” will eventually be restored.

As a lagging middle power, Canada needs to take a realistic review of our place in the world and articulate a national security strategy. We also need to ask ourselves some hard questions before embracing a new human foreign spy agency.

What are we fixing? What are the gaps we are trying to fill? Who and what are we targeting? Do we envisage ourselves having a paramilitary organization like the CIA or MI6? What would the return on investment actually be? Have we fully utilized open-source intelligence with our covert capabilities and authorities? Are all levels of government, the private sector, and the Canadian public well enough informed on national security trends and threats? The answer to all of these questions is: no, not really.

Canada already has significant networks and assets (both public and private) at home and abroad. We also know that the home game is paramount. We have the essential ingredients in our national security ecosystem for enhanced foreign intelligence collection and analysis. This is where we need to start. What is required are the leaders, the clear direction, and the support for calculated risks that will enable our national security practitioners to succeed.

We are clearly in a time of multiple crises and we are at a crossroads. We need to keep our eye on the ball. The priorities are rebuilding our defence mission and bolstering our economic security. So, when it comes to a bricks and mortar foreign spy agency, never say never, but now is certainly not the time.

Martin Green is a senior adviser at Global Public Policy in Ottawa, and is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He is a former assistant secretary to cabinet, intelligence assessment at the Privy Council Office.