This article originally appeared in the Hill Times.

By Ken Coates, February 5, 2024

Canada’s innovation conversation has sure changed.

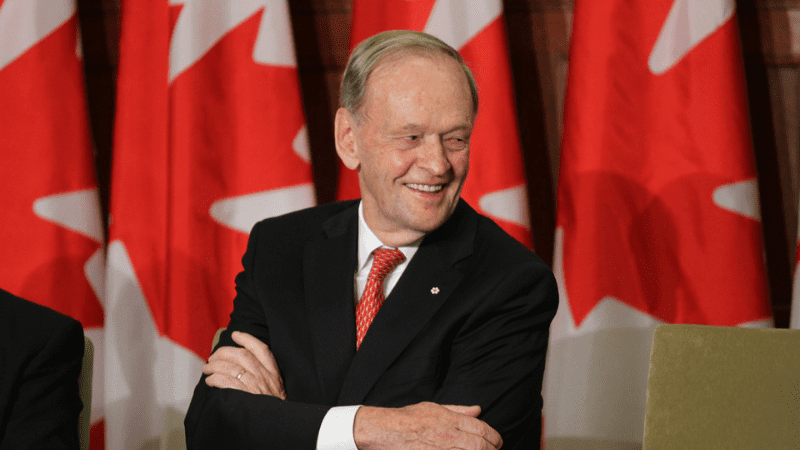

In then-prime minister Jean Chrétien’s last term, innovation was held as Canada’s great economic hope. Expand the universities. Hire hundreds of Canada Research Chairs. Create the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, and give it a start-up contribution of several billion dollars. Expand academic research funding. Create subsidy programs for scientific and technical research. Open commercial incubators. Expand Canadian-owned intellectual property.

The country did all of these things and more. Billions of dollars have been spent on the Canadian version of the widely implemented national innovation “equation.” Universities and research institutes threw themselves wholeheartedly into the enterprise. So did many communities, with conspicuous successes (Waterloo, Fredericton, and Kelowna) but generally limited achievement. Some companies flourished, like Open Text, and others languished, like BlackBerry. Potential commercial superstars continue, like Ballard Power, but at less than three per cent of its peak market capitalization in 2000.

What did Canada get for its investments, beyond hundreds of press conferences and ribbon cuttings, many government announcements, and millions of hours spent applying and accounting for government grants? The answer is far from ideal.

Our national competitiveness is falling, and Canadian GDP forecasts for the coming decades have us near the back of the OECD. Far from the innovation-fuelled, research and education-driven robust economy promised by the advocates of scientific and technological innovation, we have a country where the only real growth industry is government, where the future of our cornerstone resource sectors are in doubt, and where universities have been made curiously dependent on international student fees.

The problem is even greater than this. Entrepreneurship—never this nation’s roaring strength—appears to be in decline. Investment capital remains tight, save for that for residential construction that moves slowly in the same direction as rapid urban population growth. Canadian innovation, often paid for in substantial measure by government grants, loans and subsidies, is highly mobile, often accompanying the inventors and entrepreneurs out of the country.

This does not mean that advocates of innovation were and are wrong. In the highly competitive and tumultuous global economy, radical economic transformation remains a clear avenue toward prosperity. There are numerous success stories, and not just in Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver. The high-tech sectors in Victoria, Edmonton, Saskatoon, Sherbrooke, and Halifax are doing well. But on a national scale, the country falls short of both its lofty aspirations and many competitor nations. Smaller cities, rural areas, and northern communities, all of which would benefit from focused commercialization of technology, have been largely left out of the innovation economy.

Canadian efforts to build a new economic order have foundered on two very different forces. First, the country’s traditional reliance on natural resources has protected the country from the vicissitudes of the global economy. Even as the federal government tries to undermine the oil and gas sector and constrain the mining industry, the nation’s economy relies heavily on oilsands activity and revenues, and on the industrial activity associated with drilling, extraction, and pipelines. Central Canadians struggle to appreciate the central role energy plays in national prosperity, and the risks associated to interfering with proper development. But even as Canadians largely ignore the western Canadian resource sector, it remains the backbone of national prosperity.

More ominously, Canadians have become remarkably dependent on government payments and subsidies. Even before the pandemic and CERB took reliance on government spending to new levels, our innovation efforts had become substantially dependent on government financial support. The nation’s greatest new economy initiative—excepting some remarkable largely private investments in transformation in the oil sands and broader energy industry—is a dramatic multi-billion-dollar subsidy for EV battery plants in central Canada. Innovation that is routinely propped up by government funding is neither sustainable in the long-term, nor likely to be internationally competitive.

Canada’s innovation challenges will not be overcome by another government program or an infusion of more federal cash. This has not worked in the past, and it is unlikely to do in the future. The fundamental goal must be to unleash domestic creativity and entrepreneurship. To get here, Canada must—like Norway—embrace its energy wealth, and use the wealth to fuel commercial development. Government direction and innovation management has produced some results, but they are meagre compared to the spending and even less compared to the opportunity.

Our national innovation economy needs real innovation. It needs honest talk about our national strengths and weaknesses, and a realization that sustaining entrepreneurship is more crucial to the next economy than scientific discovery. It has taken Canada billions of dollars in ever-so-optimistic government spending on innovation to realize that the current pattern does not work. Sadly, it is not yet clear the lesson has been learned.

Ken Coates is a professor of Indigenous governance at Yukon University, and formerly the Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation in the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. He is also a distinguished fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Aboriginal and Northern Canadian Issues.